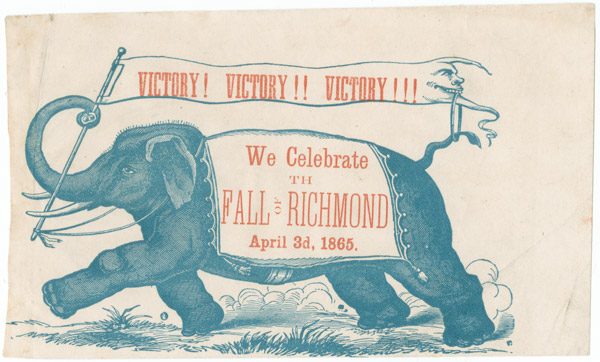

Republicans Celebrate the Fall of Richmond, 1865 (Richmond, Virginia Fell to Union Forces on 3 April 1865)

Before Confederate forces retreated across the James River and south of the city, they set fire to storehouses of tobacco and supplies on the riverfront. Spread by winds and aided by disorderly residents and soldiers, the fires went unchecked, burning a large part of the city's warehouse and business districts, and narrowly avoiding the destruction of the Capitol building. When Union troops entered the capital of the Confederacy, their first task was to battle the flames and save the city from complete ruin. The Civil War was effectively over six days later when General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870) surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) at Appomattox Court House. (source: Virginia Memory)

More than 25 percent of buildings in Richmond, Virginia, were destroyed by fires set by retreating Confederates in April 1865. Above, two women in the "burnt district." Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

On April 1, 1865, General Lee advised Confederate President Jefferson Davis to abandon Richmond, the Confederate capital. In order to prepare for invasion, the army ordered the destruction of supplies including liquor, tobacco, cotton, clothes, food, and ammunition. The burning of these supplies became out of control, and the center and business district of the city burned, including Tredegar Iron Works.

The last three photographs show the destruction endured during General Sherman’s aggressive campaign in 1864. These photographs provide samples of destruction from the cities of Charleston, Columbia, and Atlanta. These photographs were taken by George Barnard, who was the assigned photographer to General Sherman.

Confederates burned Richmond, Virginia, their capital, before it fell to Union forces in April 1865.

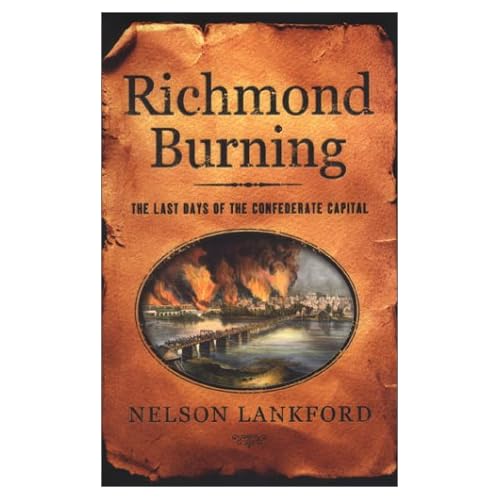

From H-Net: Nelson Lankford's book, Richmond Burning: The Last Days of the Confederate Capital reviewed by Kevin Levin in an article entitled, "Finding Meaning in the Fall of Richmond" in September 2003 -- On April 5 of this year a bronze statue of Abraham Lincoln and his youngest child, Tad, was unveiled in Richmond commemorating their visit to the city shortly after the arrival of Union forces. Commissioned by the United States Historical Society, Lincoln and his son are seated on a bench against a plain granite wall. The words, "To Bind Up the Nation's Wounds" are cut into a granite capstone. Those who followed this story know that the unveiling was accompanied by a great deal of controversy and emotion. The commander of the Virginia Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, called the work "a slap in the face of a lot of brave men and women who went through four years of unbelievable hell fighting an invasion of Virginia led by President Lincoln." Another likened a Lincoln statue in Richmond to erecting a monument to Adolf Hitler in Jerusalem. Lincoln historian Harold Holzer, co-chairman of the U.S. Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, supported placing the statue in Richmond "as an historical symbol of reconciliation." Richmond National Battlefield Park Superintendent Cynthia MacLeod said that Lincoln's visit "was, and is, nationally significant and this statue will bolster our effectiveness in telling that story." This heated debate suggests that the fall of Richmond and the Civil War still has a tight hold on popular memory. The publication of Richmond Burning serves as a fruitful entry point into the history behind this continuing fascination and attachment to the final days of our nation's civil war.

Though the fall of Richmond did not signal the surrender of all Confederate armies, for many Southerners it did provide sufficient evidence that their bid for independence would not be realized. Nelson Lankford, who edits The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography published by the Virginia Historical Society, uses the final days of Richmond to weave together an array of stories that provide insight into how the residents of Richmond, from Jefferson Davis to the city's slave population, interpreted the swirling events that took place there in early April 1865. Reactions from the city's white population varied. For Fannie Dickinson, the arrival of Union troops meant the end of the world as she knew it, while Elizabeth Van Lew rejoiced as Union regiments raced one another toward Capitol Square. The slave population welcomed the army, which included regiments of U.S. Colored Troops as liberators. Accompanying the 28th USCT was Reverend Garland White who was born in Richmond as a slave and later escaped to the North where he recruited African Americans for the Union army. After he had addressed a crowd on the edge of the city, an older woman approached and said, "[t]his is your mother, Garland, whom you are talking to, who has spent twenty years of grief about her son" (p. 127).

The central focus of the book is the fire on April 2 and 3, and Lankford goes to great lengths to explain the breakdown in communications that led to General Richard Ewell's order to destroy buildings that contained tobacco. With the support of Secretary of War John C. Breckenridge, Ewell believed that a fire could be contained. Others, including Chief of Ordnance Josiah Gorgas and Richmond mayor Joseph Mayo, questioned whether the destruction of the buildings was even necessary. No one seems to have been concerned that the wind would render any thoughts of a contained fire otiose. Compared with the pictures of the devastation as seen in photographs taken of Richmond after the fire, Lankford reminds the reader that nine-tenths of the city's commercial district was consumed by the fire, including eight hundred buildings. In addition to the physical damage, Lankford catalogues other losses, including valuable state documents and other historical items. "Letters of George Washington and two-hundred-year-old colonial indentures fluttered in the breeze" (p. 184).

Though the book's strength is its strong narrative, Lankford does place his story in a broader historiographical context. Ultimately, the fall of Richmond was due to Union military superiority in the wake of the fall of Petersburg and not to internal fissures. Unlike previous studies that emphasize the beginning of reconciliation between the two warring sides, Lankford reminds the reader that Southerners stubbornly resisted the reality of Union occupation. Stories suggesting early signs of reconciliation such as Lincoln's courtesy call to the home of General George Pickett, Union Major Genernal Godfrey Weitzel's decision to send a "wallet stuffed with greenbacks" to his old "West Point chum" Fitzhugh Lee, and Robert E. Lee's courageous move to kneel and pray next to a black man at St. Paul's are all challenged. According to Lankford, all three stories "are filled with a spirit of reconciliation and of hope for the future of the broken country, reunited by force of arms and facing an uncertain road ahead" (p. 243). In the end, however, the stories contain more myth than fact.

Lankford steers the reader through Lincoln's triumphal entrance into the city and tour of Jefferson Davis's White House, but also discusses in some detail lesser known stories such as the president's desire to restore the Virginia state legislature to vote the state out of the Confederacy, thus ending hostilities much sooner. Lankford's interest in this story is a perfect example of the book's attention to the contingency of the past. Looking back on events at the beginning of April 1865, it is easy to fall into the habit of drawing connections of inevitability between important dates. A full week lapsed between the government's abandonment of Richmond and Lee's surrender at Appomattox on April 9. Even after entering Richmond on April 4, Lincoln could not be certain that the end of the military conflict was anywhere in sight. Lincoln eventually rescinded the offer to restore the legislature on April 12, only after circumstances had changed in the Union's favor. Lankford's focus on the limited perspectives of the participants reminds readers not to make the mistake of reading back into the past.

By the following summer, visitors to Richmond would have witnessed a city in the process of rebuilding. Though the physical destruction was easily repaired, according to Lankford, "passions did not die so quickly" (p. 245). Virginia Unionist and former U.S. Congressman John Minor Botts blamed the war and destruction on the secessionists and praised General Ulysses S. Grant for delivering the South from "military despotism." On the other side of the spectrum, former Richmond Examiner editor Edward Pollard held Jefferson Davis responsible for the fall of Richmond, and castigated Grant for his use of unrestrained force. Even in defeat, according to Pollard, the Confederacy could claim to have acted out of the highest virtues of chivalry and humanity. At the same time, Richmond's African-American community organized a march to celebrate the first anniversary of occupation. Not surprisingly, white Richmonders were appalled and though they attempted to stop the celebration, in the end around two thousand men and women took part in the festivities. The multiple meanings attached to the fall of Richmond and Confederate defeat continue to resonate in popular culture and "cannot be masked by the warm sepia glow cast over our great national trauma by popular books and documentary films" (p. 248).

Lankford's sharp prose and command of a broad range of primary and secondary sources make this book a pleasure to read. Returning to the heated debates surrounding the Lincoln statue, this book might also help create a more historically grounded and meaningful dialogue between those who embrace radical positions in the debates about how the Civil War should be remembered. (source: H-Net)

No comments:

Post a Comment