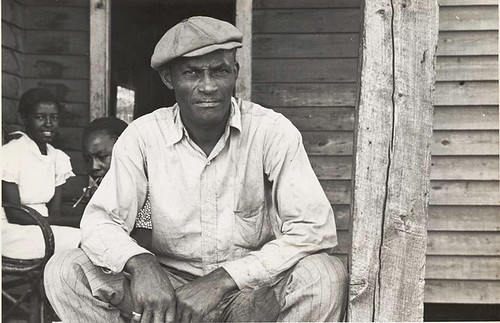

Not Free Yet

Freed by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1865, former slave Henry Adams testified before the U.S. Senate fifteen years later about the early days of his freedom, describing white planters' unfair labor practices and the violent, intimidating atmosphere in which ex-slaves felt compelled to work for their former masters.

The white men read a paper to all of us colored people telling us that we were free and could go where we pleased and work for who we pleased. The man I belonged to told me it was best to stay with him. He said, "The bad white men was mad with the Negroes because they were free and they would kill you all for fun." He said, stay where we are living and we could get protection from our old masters.

I told him I thought that every man, when he was free, could have his rights and protect themselves. He said, "The colored people could never protect themselves among the white people. So you had all better stay with the white people who raised you and make contracts with them to work by the year for one-fifth of all you make. And next year you can get one-third, and the next you maybe work for one-half you make. We have contracts for you all to sign, to work for one-twentieth you make from now until the crop is ended, and then next year you all can make another crop and get more of it."

I told him I would not sign anything. I said, "I might sign to be killed. I believe the white people is trying to fool us." But he said again, "Sign this contract so I can take it to the Yankees and have it recorded." All our colored people signed it but myself and a boy named Samuel Jefferson. All who lived on the place was about sixty, young and old.

On the day after all had signed the contracts, we went to cutting oats. I asked the boss, "Could we get any of the oats?" He said, "No; the oats were made before you were free." After that he told us to get timber to build a sugar-mill to make molasses. We did so. On the 13th day of July 1865 we started to pull fodder. I asked the boss would he make a bargain to give us half of all the fodder we would pull. He said we may pull two or three stacks and then we could have all the other. I told him we wanted half, so if we only pulled two or three stacks we would get half of that. He said, "All right." We got that and part of the corn we made. We made five bales of cotton but we did not get a pound of that. We made two or three hundred gallons of molasses and only got what we could eat. We made about eight-hundred bushel of potatoes; we got a few to eat. We split rails three or four weeks and got not a cent for that.

In September I asked the boss to let me go to Shreveport. He said, "All right, when will you come back?" I told him "next week." He said, "You had better carry a pass." I said, "I will see whether I am free by going without a pass."

I met four white men about six miles south of Keachie, De Soto Parish. One of them asked me who I belonged to. I told him no one. So him and two others struck me with a stick and told me they were going to kill me and every other Negro who told them that they did not belong to anyone. One of them who knew me told the others, "Let Henry alone for he is a hard-working nigger and a good nigger." They left me and I then went on to Shreveport. I seen over twelve colored men and women, beat, shot and hung between there and Shreveport.

Sunday I went back home. The boss was not at home. I asked the madame, "where was the boss?" She says, "Now, the boss; now, the boss! You should say 'master' and 'mistress' -- and shall or leave. We will not have no nigger here on our place who cannot say 'mistress' and 'master.' You all are not free yet and will not be until Congress sits, and you shall call every white lady 'missus' and every white man 'master.'"

During the same week the madame takin' a stick and beat one of the young colored girls, who was about fifteen years of age and who is my sister, and split her back. The boss came next day and take this same girl (my sister) and whipped her nearly to death, but in the contracts he was to hit no one any more. After the whipping a large number of young colored people taken a notion to leave. On the 18th of September I and eleven men and boys left that place and started for Shreveport. I had my horse along. My brother was riding him, and all of our things was packed on him. Out come about forty armed men (white) and shot at us and takin' my horse. Said they were going to kill ever' nigger they found leaving their masters; and taking all of our clothes and bed-clothing and money. I had to work away to get a white man to get my horse.

Then I got a wagon and went to peddling, and had to get a pass, according to the laws of the parishes, to do so. In October I was searched for pistols and robbed of $250 by a large crowd of white men and the law would do nothing about it. The same crowd of white men broke up five churches (colored). When any of us would leave the white people, they would take everything we had, all the money that we made on their places. They killed many hundreds of my race when they were running away to get freedom.

After they told us we were free -- even then they would not let us live as man and wife together. And when we would run away to be free, the white people would not let us come on their places to see our mothers, wives, sisters, or fathers. We was made to leave or go back and live as slaves. To my own knowledge there was over two thousand colored people killed trying to get away after the white people told us we were free in 1865. This was between Shreveport and Logansport.

[source: PBS -- Excerpt from Senate Report 693, 46th Congress, 2nd Session (1880). Reprinted in Dorothy Sterling, editor, The Trouble They Seen: The Story of Reconstruction in the Words of African Americans. New York: Da Capo Press, 1994.]

No comments:

Post a Comment