The Politics of Disfranchisement

From H-Net, by Lewie Reece, on July 2001 -- Students of southern political history have long recognized the impact of disfranchisement. The process by which southern state legislatures and constitutional conventions stripped African-Americans and poor whites of the ballot has long been deemed an important event. Yet understanding the meaning of that event has often proved illusive. To date, the most significant work on disfranchisement has been that of J. Morgan Kousser. Kousser's The Shaping of Southern Politics was an immediate classic, and remains the most important book written on Post-Reconstruction southern politics. Kousser demonstrates clearly that Republicans, far from disappearing from politics after Reconstruction, remained a vibrant force in the region's politics until disfranchisement.

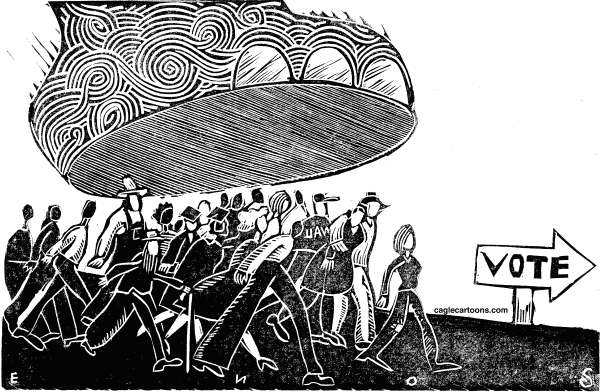

From Kousser's perspective, disfranchisement was an event necessitated by the deep pressure that planter elites felt from opposition politics in the late nineteenth century. It was not poor whites who transformed the political system, but rather the planter elite who, through their control of the legal process at the state legislative level and at state constitutional conventions, eliminated the political opposition. Law then is at the center of Democrats' attempts to create a political universe in which their power was unchallenged. Kousser also clearly demonstrates that political democracy was effectively dead in the South by the early 1900s, never again to revive until the civil rights revolution of the 1960s.

Perman's work builds upon many of the important conclusions that Kousser reached about the workings of the southern political system. It is an attempt to examine in great detail the process through which southern states disfranchised the political opposition. Perman delves into the thought processes of those who pushed disfranchisement forward. His interest and heavy investment of effort in archival materials allows him to provide an interesting picture of the Democratic political establishment. They are a morally repellant lot, but Perman provides a much more detailed examination of their motivation and influence. Many of the southern politicians who exercised such influence have been given little attention within the larger historiography of southern politics and so Perman's observations have real merit. His portrait of Ernest Kruttschnitt, the leader of disfranchisement forces in Louisiana, is expressed with particular talent and skill.

Perman provides a much more detailed description of these political leaders than anything we have had previously, and presents an important appreciation of the people who led the drive to disfranchisement. His work reveals a palpable political fear in these leaders' approach to disfranchisement. Disfranchisement was never an afterthought, but a calculatingly determined move on the part of a political elite who were consumed by racism and resolved to crush biracial democracy in the South.

Perman's approach to detailing the story of disfranchisement in the South is to describe the way in which it developed throughout the region chronologically, state by state. This methodology reflects the reality that while disfranchisement was a movement which developed across the entire South, it was also remarkably local. He clarifies the different dynamics particular to each state. One of the real strengths of Perman's account is the appreciation of these differences, as well as the various factional differences within the Democratic party. His focus on the different cadences of statewide politics allows him to show considerable appreciation of the different problems the planter elites struggled to overcome. His narrative is told in an engaging style, and reflects a real gift for making some of the more complicated political maneuvering comprehensible.

One of the other important elements in Perman's text is his appreciation of the long term significance of disfranchisement's impact on political development in the South. Perman clearly describes the onset of segregation, and the way race remained a central part of a disfranchised southern political culture. The events of disfranchisement thus have a considerable legacy, one that proves to be remarkably long lasting.

Equally valuable are the connections which Perman shows between events in the South and the increasingly racist cast of national politics in the Progressive Era. Little attention has been focused on the way in which the McKinley Administration consciously undermined Republican support for civil rights. The chapters which explain the movement away from civil rights as a national issue are quite effective, and have a certain emotional power. Historians of Progressivism have often accepted racism in national politics rather than studying it in sufficient detail, and these sections of the book are particularly instructive.

Perman's book is an important contribution to the historical literature. It does however, suffer from interpretive flaws. We can assign these flaws to current understandings of the period, as much as to Perman, but they do limit the impact of his work. First, although Republicans, and their junior partners the Populists, make an occasional appearance in Perman's text, the book is largely a study of how planter elite Democratic politicians disfranchised southern politics. We learn very little about southern Republicans and Populists during the disfranchisement campaigns. Since Republicans and Populists actively resisted disfranchisement on a consistent and determined basis, the absence of their story is a major gap.

Perhaps in some ways this reflects that historians have refused to take the role of post-Reconstruction southern Republicans seriously. As a result, the significance of African-American political activism is largely lost. This is however, a problem not simply with Perman's excellent discussion, but rather with the limitations of current southern political history.

One might wish as well, that Perman could have given more attention to the manner in which disfranchisement was a legal process. Disfranchisement, regardless of the form taken, was simply the imposition of legal statutes, regulations, and constitutions that restricted who could and could not register to vote. These laws had the effect of purging the electoral system of a multitude of voters who simply could not comply with the legal restrictions the various states imposed. The effect of these mechanisms was the denial of the ballot to African-Americans and poor whites, thereby insuring the power of the wealthy which dominated the Democratic party in the South. If disfranchisement was a revolution, and I think it was, then it was a legal revolution, as well as a political one.

Nevertheless, despite these qualms, it should be said that Perman's book makes a signal contribution to the study of disfranchisement. Struggle For Mastery provides a far more detailed examination of the southern political elite than anything we have had previously. It provides very detailed descriptions of the way in which disfranchisement worked, especially as a local and statewide movement. Perman also makes a real effort to integrate such a study of disfranchisement within a broader national focus. Historians of post-Reconstruction southern politics will find Struggle For Mastery an important book which merits serious examination. (Copyright 2001 by H-Net, all rights reserved.)

No comments:

Post a Comment