Street Scene in Mound Bayou, Mississippi

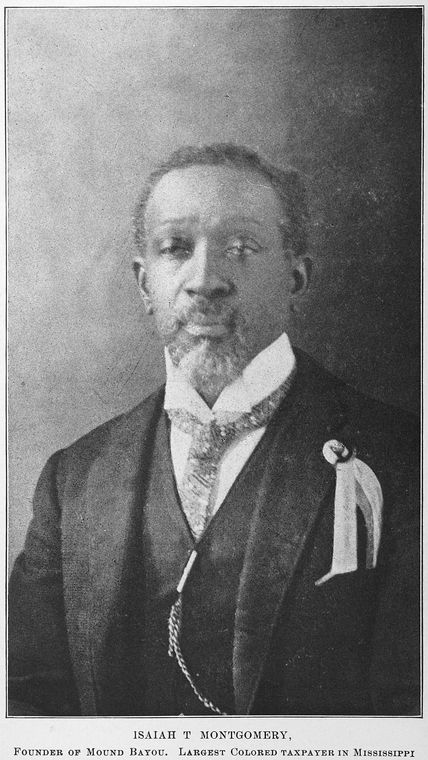

From Mississippi History Now, " The Political Life of Isaiah T. Montgomery: Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part II)," by Neil R. McMillen, Ph.D., on February 2007 -- Isaiah T. Montgomery might be called Mississippi’s Booker T. Washington. Though Montgomery was not as famous or as influential, his life and work in many other respects closely paralleled that of the great educator at Tuskegee Institute, a college for black people in Alabama. They were both thought by influential whites to be conservatives, “safe and sensible” African-American leaders who understood that if the freed slaves and their descendents were to get along in the Jim Crow South, they must go along with racial separation and black political disfranchisement. Both were regarded by contemporary black “militants” (few of whom lived in the South) as faithless collaborators who sold out their people in the darkest hours of post-Civil War radical white racism.

Booker T. Washington speaking in Mound Bayou, Mississippi

In fact, though Montgomery spent most of his adult life overshadowed by Washington, it was he, not the Tuskegean, who first won public prominence as the architect of an unequal bargain that seemed to trade the civic aspirations of blacks for the empty white assurance of racial harmony. Half a decade before Washington offered his “olive branch,” his famous “Atlanta Compromise Address” of 1895, Montgomery delivered up his “peace bush,” his conciliatory speech to the Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890, in which he accepted wholesale black disfranchisement as the essential “beginning of the end of the great race question.” As historians now know, neither Washington nor Montgomery was what he then seemed. Both were in fact complicated pragmatists who were misread by their white admirers and misunderstood by their black detractors.

Race statesman (or race traitor?)

History would remember Montgomery not just as a town builder, but also as a conservative “race statesman” who pursued racial harmony through accommodation. In some respects he was an unlikely advocate of black disfranchisement as a path to peace. He himself had regularly voted since the early days of Reconstruction at Davis Bend when the freedmen first won the right to vote. His father and brother both held minor offices and were very likely the first blacks to hold public office in Mississippi and perhaps the entire South. After Reconstruction, Montgomery was well-known and active in Bolivar County Republican circles, and his beloved Mound Bayou remained a faithful island of Republican loyalty in a sea of white Democrats. He served for a time as the town’s mayor, and he later took more than a little pride in the fact that it elected its own public officials. He was elected as a Republican delegate to the Mississippi Constitutional Convention in 1890, and he later accepted a federal political patronage job as a collector of government monies.

But Montgomery was also an astute political observer and he understood the realities of power in his time and place. Enfranchised by the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and technically allowed an equal opportunity to both vote and hold public office under the Mississippi Constitution of 1868, blacks outnumbered whites in every decade from 1840 to 1940. Clearly, in this black majority state of Mississippi, the first requirement of unchallenged white rule was black disfranchisement. Having re-established white control by force and fraud in 1875, the “white line Democrats” — or “Redeemers” as they styled themselves — intended to dominate the political life of Mississippi by any means necessary. With an accommodating federal government increasingly willing to purchase North-South reconciliation by looking the other way, no prudent black Mississippian could ignore that fact.

And Isaiah Montgomery, like his father before him, was nothing if not prudent. His father, Ben, chose his battles carefully. Eager to avoid racial conflicts that he could not hope to win, he had made it his life-long practice to cultivate friendships with influential whites. Ben set whites at ease by downplaying black political aspirations, by affirming that voting was of “doubtful and remote utility” to the freedmen. Discussions of the “suffrage question,” he publicly asserted, are “more likely to produce contention and idleness than harmony.” These were calculated and soothing words, suggesting to whites, as one approving white newspaper editor put it, that Ben was a “sensible darky” and a “good citizen” who “attends to his own business [and] does not dabble in politics.”

Isaiah too was a skillful actor in the ceremony of submission required of any African American who would “stay right” with whites. “This is a white man’s country,” Montgomery said more than once, “let them run it.” His advice to black Mississippians who still demanded a citizen’s right to vote was equally direct: “The farther you stay away from the white people’s politics, the better.” It was not surprising, then, that Montgomery, alone among black Republicans, was allowed to represent his race and his party at the state Constitutional Convention of 1890. He was an “elected” delegate from Bolivar County, of course, but even casual observers of the Mississippi political scene could no longer have illusions about the integrity of the ballot box. According to one prominent judge, J. J. Chrisman — himself a leading member of the constitutional convention — it was “no secret that there has not been a full vote and a fair count in Mississippi since 1875.”

Once assembled, the convention’s over-riding purpose was plain to see. “We came here to exclude the Negro,” S. S. Calhoon, the body’s president, announced. “Nothing short of this will answer.” Montgomery was assigned to the Committee on Elective Franchise and he spoke eloquently in favor of, and voted for, a measure to “purify the ballot” by restricting it to literate adult males, those he called the “stable, thoughtful, and prudent element of our citizens.” The burden of a literacy restriction, as he well knew, would fall most heavily on a people so recently freed from slavery. But he also knew that, through education, illiteracy could eventually be eradicated and he dared to hope that, in the meantime, voter requirements would apply equally to both races and that such disfranchisement that would come to the Negro would come “because he is ignorant” not “because he is black.” He was then just forty- three years old, but it would prove to be his defining moment and the single most controversial act of his long and complicated life.

But why? Why was Montgomery “elected” as a delegate? Why was he willing to serve? Why did he support disfranchisement? His presence at the convention is perhaps most easily explained: his conservative ideas were well known to powerful white political leaders eager to point to his example as proof that the convention was “fair” and that blacks, too, favored white supremacy. In a word, Montgomery provided “cover,” a measure of “legitimacy,” as Mississippi enacted the “legal” measures to subvert the Fifteenth Amendment.

Montgomery’s own motivations and behavior are more complex and have defied easy answers for more than a century. Some conservative black contemporaries applauded his tone of racial sacrifice, his singular “act of statesmanship.” But others recoiled in shock and horror, dismissing him as a “great disappointment,” a “traitor,” the “Judas of his people.” It was said that he was either so blinded by ambition or so eager for white approval that he traded his vote for the empty favor of a seat at the convention. Or that he bought immunity from white interference in the affairs of Mound Bayou with the coin of black suffrage. Or, more frequently, that his actions were simply “inexplicable,” an “unfathomable” mystery wrapped in a “jangle of contrarieties.”

Yet, examined in the context of his life and his times, his role at the convention seems neither treasonous nor puzzling nor inconsistent. By supporting a white supremacist initiative, he offered a way to end the “grave dangers” of racial conflict, “bridge” an ever-widening and deepening racial “chasm,” and “inaugurate an era of progress.” The black right to vote in Mississippi, as he reasoned, had already been nullified by electoral fraud and by physical and economic coercion. By giving away rights they could no longer exercise anyway, Afro-Mississippians might gain the personal security and economic freedom necessary to advance themselves. Thus, given a “man’s chance,” having been allowed to prove their worth through right living, hard work, and practical education, the former slaves and their descendents could expect someday to re-enter the body politic as equal citizens, free from the burden of racial prejudice.

Or so Montgomery dared to hope. It was a long shot, but it was, in all fairness, the only shot Montgomery thought he had. The suffrage restrictions of the new constitution, as he informed a northern newspaper just two weeks after his fateful vote, “did not wholly suit me . . . but it was the best that could be done. We had to take the best that we could get.” Of course, Montgomery’s “peace bush,” his “fearful sacrifice laid upon the burning alter of liberty,” was not the beginning of the end of the race problem. It did not, as he hoped, open the way in Mississippi for political divisions “upon some basis other than that of color or race.” Clearly, his faith in ultimate white good intentions was misguided. But to suggest that Montgomery’s strategy of “giving up to gain” was fundamentally ill-conceived is not to prove that he had other realistic options.

In time, Montgomery had second thoughts about his “sublime sacrifice” of 1890. He lived another thirty-four years, long enough to admit privately — though never in public — to a sense of betrayal, to a recognition that white supremacists in Mississippi sought “nothing less than a retrogression of the Negro back towards serfdom and slavery.” In a letter to Booker T. Washington, he acknowledged that white talk of “pure government” was a sham, that only armed federal intervention could restore color-blind democracy to Mississippi. To have said that openly would have been to speak against the very grain of his being; not least, it would have risked swift and certain retribution for himself and his town. But by remaining publicly silent, he opened the way to the misunderstandings and the calumny that have dogged his reputation for more than a century. When Montgomery died in 1924 he was eulogized by a conservative white planter-politician, Walter Sillers Sr., and laid to rest in a tomb paid for by white subscription. Outside his circle of family and friends, however, he was largely unmourned. By that date he was, in the words of a northern missionary, “more hated by Negroes” than any other Mississippian of his race.

Isaiah Thornton Montgomery’s story tells us, if it tells anything, that human lives can only be examined in the larger context of their own times. Montgomery was assuredly not a man for all seasons. He did not speak for aspiring freedmen of his own generation who still found hope for full citizenship in the forgotten promises of Reconstruction. Nor did he speak for unborn generations who in a more opportune age after World War II would help pull down the morally corrupt house of Jim Crow. Rather, like most other mortals, he was a man of his own era, in his case a dark era of diminishing black opportunities. Among the earliest of the great black accommodators, he came of age amid the confusions of the American Civil War and Reconstruction, and he spent the middle and later years of his life awash in a rising tide of radical white racism.

Montgomery enjoyed some astonishing successes. In his personal life, as both slave and citizen, he defied white stereotypes. Though slight and small of stature (weighing perhaps 135 pounds in middle age), he was every inch an aristocrat, an educated, articulate, prosperous planter-businessman. Finding his people locked out of the American mainstream, he built in the form of the small but symbolically important city of Mound Bayou a separate and promising all-black world. If, through the thicket of racial hate and violence that was Jim Crow Mississippi, he did not find a path that balanced black dignity and progress with interracial harmony, it must be said that no other leader of his generation did either.

Perhaps, given the daunting constraints of his time and place, Montgomery’s story should end with a question: Had he been born the year he died, soon after World War I, had he lived to experience the liberating forces that flowed across the American landscape after World War II, could anyone say with confidence that this gifted mortal would today be remembered as Mississippi’s Booker T. Washington, its Great Accommodator? (source: Mississippi History Now)

No comments:

Post a Comment