THE WANDERER: THE LAST AMERICAN SLAVE SHIP AND THE CONSPIRACY THAT SET ITS SAILS , By Erik Calonius, REVIEWED BY KIMBERLY PALMER

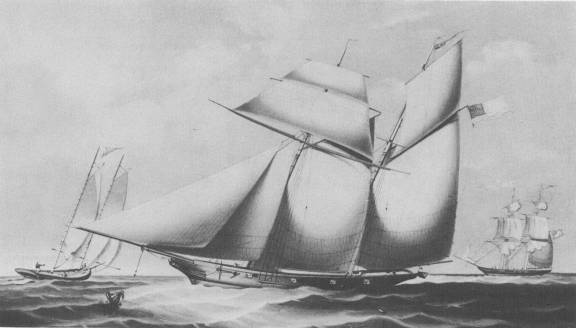

From the The Washington Times -- On July 4, 1858, a ship called the Wanderer left Charleston, S.C., and set sail for the Congo. Disguised as a luxury cruise ship, the Wanderer had first raised suspicion when it docked in Long Island and loaded far more supplies than usual for a casual cruise. Officials surmised (correctly, as it turned out) that the ship was a slave ship.

In “The Wanderer,” Erik Calonius brings to light the tale of the last known ship that brought slaves to the United States from Africa. Using newspaper accounts, letters and legal documents, Mr. Calonius, formerly a London correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and Miami bureau chief for Newsweek, reconstructs the journey in painstaking detail.

Where little or no evidence remains of the Wanderer’s voyage — including the brief excursion into Africa and the slave market where the ship’s crew purchased the slaves — Mr. Calonius writes that he used eyewitness accounts of the slave trade to describe what the slaves and the crew of the Wanderer likely experienced.

The result is a compelling and heartrending record of a journey that helped push the nation to the brink of the Civil War.

Transporting slaves from Africa was outlawed in 1820, but nearly four decades later, the practice — profitable but risky — continued. The Wanderer’s crew eluded the law by charming officials who were not all that interested in enforcing it.

When the ship reached the 3,000-mile long African shoreline, patrolled by 28 British and American ships, one of the British patrol ships spotted it. The Wanderer’s captain — William C. Corrie, a well-connected Southerner — invited the crew aboard. “After months of tedious Africa duty, the British were more than happy to explore this luxury yacht,” writes Mr. Calonius.

Corrie invited the crew to stay for dinner as well as after-dinner champagne and cigars on the deck. The British patrollers said goodbye after deciding the Wanderer was simply a cruise ship and not a slaver.

Soon after that meeting, the crew rolled up the ship’s luxury carpets and put away its library books in preparation for nearly 500 slaves. Each one was given a space that measured just 12 inches in width, 18 inches in height, and less than five feet in length — smaller than a typical slave ship.

Corrie purchased the slaves from a dealer and had them branded with a hot iron. During the return voyage, 80 slaves perished because of the harsh conditions below deck. Those that survived were unloaded in Georgia. After the Africans were spotted by locals, federal prosecutors started to build a case against the Wanderer’s owners.

Prosecutors soon found themselves up against the powerful, pro-slavery networks of Georgia. One of the ship’s owners, Charles Lamar, a wealthy Savannah resident, reminded witnesses that he could make life miserable for anyone who testified against him. Lamar was a “fire-eater” who wanted the slave trade to flourish and who hoped that the South would eventually split from the North. The nationally publicized trials of those implicated in the Wanderer scheme helped cause that rift.

“If they fail to hang the men,” wrote the New York Times of the South, “if their officials are so lax, or their juries so perjured, as to permit this trade to be carried on with impunity, in face of all our laws against it — they will suffer all the consequences of an actual complicity in the proceeding itself… . the entire population of the North will wage upon [the South] a relentless war of extermination.”

As Mr. Calonius notes, that prediction proved prophetic indeed. The defendants in the Wanderer trials were found not guilty, the abolitionist John Brown was hanged not long after and war soon broke out.

The threat of the Civil War looms throughout the narrative. In the 1850s, the South had not yet embraced the industrial revolution. Agricultural life, which depended on the labor of slaves, was idealized for its slow pace and comfortable lifestyle. At the same time, the South’s economy was slipping further and further behind the more industrialized North.

By 1860, New England was manufacturing three times as many goods as the South. In the meantime, the South, which had grown dependent on the cheap labor of slaves, had to deal with the reality that as fewer slaves were shipped from Africa, the cost of owning slaves increased. Few businesses, Mr. Calonius writes, were more profitable than the illegal transportation of slaves from Africa to the United States.

Mr. Calonius challenges the popular belief that most Southerners rallied to fight for slavery. According to him, the South seceded because a few powerful men wanted to keep slavery alive, and they persuaded many others to support their fight against what they saw as Northern interference.

Most farmers and merchants, he writes, had no stake in slavery whatsoever and even less interest in breaking up the country over it. In Savannah, the vast majority of residents did not own slaves. To garner support for slavery, the rich plantation owners who needed slaves to maintain their wealth started a campaign to convince people that if slaves were freed, they would plunder and steal throughout the region.

“It was not the first time in history that a group of radicals had overwhelmed the will of a weak and unfocused majority, nor would it be the last,” writes the author.

For most of the book, Mr. Calonius focuses on the saga of the ship and not the slaves themselves. But one of the most compelling tales comes at the end, when he recounts what happened to Cilucangy, a slave brought over on the Wanderer as a boy.

After the Civil War, Cilucangy worked in Georgia as a basket weaver. Despite his desire to return to Africa as an adult, he failed to amass the necessary funds. He started a family in Georgia, and his descendants include lawyers and teachers.

Margret Higgins, Cilucangy’s great-granddaughter, lives near the Uniondale exit of the Long Island Expressway. Her grandson was named Alexander Cilucangy Valenti, in honor of the courage and resiliency of his forebear. (source: The Washington Times)

No comments:

Post a Comment