Kevin Drum reports in Mother Jones, on 14 December 2011: Hey, guess what? Debtors' prison is back! Not the fetid and dreary kind from Dickens novels, of course, but a shiny, impersonal, high-volume, 21st century variety. It all revolves around something called "in personam" debt collection, which has two stages: discovery and collection. Mike Konczal explains:

The court orders the debtor to disclose information about his property, location of his assets, etc. to help creditors track down those assets. Then the court orders certain payments to be made, which allows for collection. This court order is enforced through the court’s authority to hold debtors in contempt, which in turn is enforced through threats of imprisonment.

....So how does this go wrong? The most obvious way is that this in personam debt collection method — which should be reserved for “extraordinary” situations — is used regularly by today’s collectors. Given that a debtor’s liberty is at stake, it seems very important that there are strict rules for this practice and that these actions are used only when appropriate. But as Shepard finds, “in personam remedies are often initiated and executed on a high-volume basis and with a striking degree of informality.”

....In many jurisdictions, bail posted to get out of being jailed for contempt of the discovery process is used to pay creditors. Besides being a great deal for creditors — as noted above, people often pay a huge economic penalty to get out of jail — it functions as a de facto debtors’ prison. As law professor Alan White described this process, “If, in effect, people are being incarcerated until they pay bail, and bail is being used to pay their debts, then they’re being incarcerated to pay their debts.”

You will be unsurprised to learn that the targets of this practice seldom have lawyers, seldom know their rights, and get no help from judges. Creditors, needless to say, suffer from none of these handicaps. (source: Mother Jones).

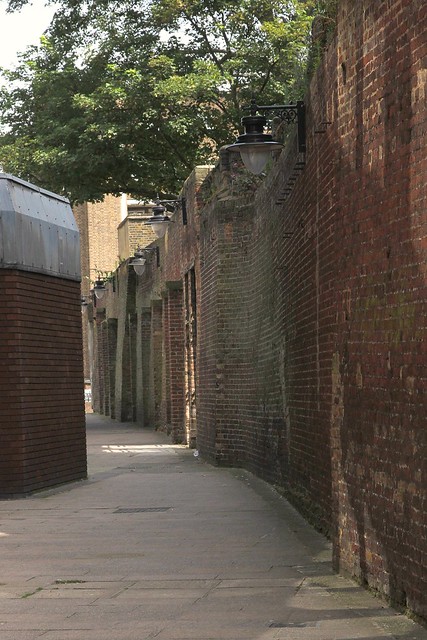

Marshalsea Prison Wall: Dickens Walk in Southwark. (www.walksoflondon.co.uk/31/index.shtml) Dickens was haunted by Marshalsea Prison. It dominates Little Dorrit, the heroine of which is a debtor’s daughter, born and raised within its confines. And Dickens was speaking from personal experience when he wrote about ‘the games of the prison children as they whooped and ran, and played at hide-and-seek, and made the iron bars of the inner gateway “Home”’. He wrote in the same novel that the Marshalsea ‘is gone now, and the world is none the worse without it’. But, as he neared the book’s completion, spurred on by letters from readers of the serialization enquiring what had become of it, he returned to look upon what remained. (source: Flicker)

Marshalsea Prison Walls, Angel Place, Southwark (L'habitant...©TonyAvon2011)The inside of the old debtors' prison walls. All that is left standing now of the dreader prison that featured so prominently in Charles Dickens' "Little Dorrit". Only the wall on the right of the picture is from the old prison. Dickens knew it well as his father had been incarcerated there in Dickens boyhood. Behind the wall, through the gates just visible (and opened now) lies a small oasis of beauty and tranquility in the old churchyard of St George's. (source: Flicker)

No comments:

Post a Comment