Alabama Governor George Wallace

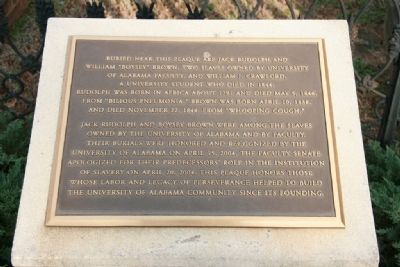

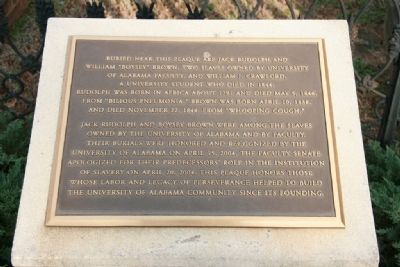

Inscription. Buried near this plaque are Jack Rudolph and William “Boysey” Brown, two slaves owned by University of Alabama faculty, and William J. Crawford, a University student who died in 1844.

Rudolph was born in Africa about 1791 and died May 5, 1846, from “Bilious Pneumonia.” Brown was born April 10, 1838, and died November 22, 1844, from “Whooping Cough.”

Jack Rudolph and Boysey Brown were among the slaves owned by the University of Alabama and by faculty. Their burials were honored and recognized by the University of Alabama on April 15, 2004. The Faculty Senate apologized for their predecessors’ role in the institution of slavery on April 20, 2004. This plaque honors those whose labor and legacy of perseverance helped to build the University of Alabama Community since its founding.

Rudolph was born in Africa about 1791 and died May 5, 1846, from “Bilious Pneumonia.” Brown was born April 10, 1838, and died November 22, 1844, from “Whooping Cough.”

Jack Rudolph and Boysey Brown were among the slaves owned by the University of Alabama and by faculty. Their burials were honored and recognized by the University of Alabama on April 15, 2004. The Faculty Senate apologized for their predecessors’ role in the institution of slavery on April 20, 2004. This plaque honors those whose labor and legacy of perseverance helped to build the University of Alabama Community since its founding.

According to the Alabama Law Review, "Professor Wants UA Apology for Slavery: Alfred Brophy will present proposal for university to consider reparations to slave descendants," on 16 March 2004, by Jeff Amy: A University of Alabama law professor wants the school to apologize for its pre-Civil War ownership and use of slaves, and to consider a commission to study the history of slave use at the school and the possibility of reparations to slave descendants.

Alfred Brophy, who studies the legal history of slavery, plans to present his proposal at today's Faculty Senate meeting. The faculty body isn't scheduled to vote on Brophy's resolution until April.

Brophy, who is white, said Monday that he has discovered numerous links between slavery and the Tuscaloosa school, established in 1831. The school owned a handful of slaves for much of its early existence, and rented others, according to Brophy's research. Professors, students and at least two university presidents owned slaves, he said.

Slaves cleaned buildings, planted trees, served students and aided professors, according to records Brophy has found. Though the professor hasn't found any direct evidence yet, he believes slaves helped build at least some of the seven surviving buildings that escaped destruction by Union troops in 1865.

But Brophy believes what UA really needs to atone for is the intellectual defense of slavery made by many of its leaders. Brophy points particularly to two university presidents and a Mobilian who founded the forerunner of the university's medical school. All three were prominent public defenders of slavery and the idea that blacks were naturally inferior. All three have buildings on the Tuscaloosa campus named for them.

So far, the resolution has caused little stir on the 20,000-student campus. Cathy Andreen, a university spokeswoman, declined comment on behalf of administrators.

"At this point, we're not ready to comment on it, because we haven't seen it," Andreen said.

Robert Turner, a senior from Tuskegee, said he had heard about some of Brophy's work, and said he hoped university leaders would support further inquiry.

"It should be something we look into, discovering the role the university played," Turner said.

Turner, who is black, is the outgoing executive chief of staff for Alabama's Student Government Association.

Vivian Malone attends class in 1963 after her admission to the University of Alabama despite Gov. George Wallace's "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door."

Success in race relations:

The University of Alabama, though famous for George Wallace's 1963 attempt to prevent integration, known as the "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door," is in some ways a success in today's race relations. The school's student body is more than 13 percent black, a higher share than Auburn University or some other Southeastern Conference schools.

Even if the Faculty Senate adopts Brophy's proposal, UA President Robert Witt or University of Alabama System trustees would have to take a similar position for the faculty action to mean anything. For example, student and faculty resolutions last fall calling for the university to condemn discrimination against gays and lesbians have so far garnered little public recognition from top UA leaders.

Among campus structures that survived the Union Army destruction are outbuildings of the 1841 President's Mansion that have been identified in the past as slave quarters. Today, they appear on university maps under names like "President's storage."

At least six buildings on the campus are named for people who owned slaves or advocated slavery, according to Brophy. He notes that Basil Manly, university president from 1837 to 1855 and Landon Garland, president from 1855 to 1865, both owned large numbers of slaves who worked the presidents' personal plantations. Manly and Garland encouraged their students to believe that slavery was part of the natural order ordained by God, according to their surviving papers and other accounts.

Brophy also points to Josiah Nott, a physician in Mobile who founded the forerunner of the University of Alabama Medical School in 1858. Nott wrote and lectured about claims that blacks were genetically inferior, based partly on skull measurements he made in his medical practice. Slavery suited black people, Nott said, because the race could never hope to achieve the level of accomplishment and civilization that whites had reached.

Vivian Malone and James Hood. Vivian Malone became the first African-American to graduate from the university.

Vivian Malone and James Hood. Vivian Malone became the first African-American to graduate from the university.

The question of whether universities profited from slavery, and what they should do to make up for it, has been a prominent subplot in a larger national debate about reparations in the last 15 years. Up until now, most attention has focused on Ivy League universities -- Brown, Harvard, Princeton and Yale.

Most recently, Ruth Simmons, the first black president of Rhode Island's Brown, appointed a committee to examine the school's ties to slavery, teach students about that history, and consider whether Brown should do something to compensate for that past.

Some black leaders have called for economic payments -- typically called reparations -- as a way for the nation to erase some of the damage caused by slavery, and share the economic gains that slave owners enjoyed. They point to reparations paid to citizens of Japanese descent whom the American government imprisoned during World War II. They also note payments by Germany and German companies to Holocaust victims.

But opponents say that idea is logistically difficult at best, and an ideological travesty at worst. Those against reparations say its unfair to tax people for the sins of previous generations. A federal judge in Chicago recently dismissed a lawsuit seeking reparations, in part because there are no slave owners or slaves still alive.

A 2002 Mobile Register-University of South Alabama poll found the state's citizens racially polarized over the question of reparations. While 67 percent of black respondents favored the federal government making cash payments to slave descendants, only 5 percent of white respondents agreed. Pollsters said some white people became so upset that they had trouble finishing telephone interviews for the poll.

Vivian Malone and James Hood register for classes at the University of Alabama despite Alabama Gov. George Wallace's "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door" protesting racial integration of the institution.

Favors reparations:

For his part, Brophy has favored reparations. As a law professor in Oklahoma, he counseled black residents of Tulsa in their efforts to gain compensation for a 1921 race riot that left numerous blocks of a black business district in ruins and may have killed 300 people.

He thinks it might be possible to track down descendants of slaves owned by the university and its early professors, to offer them scholarships or some sort of symbolic payment. He acknowledged, however, that such an effort would provoke widespread opposition.

"I'm not going to fall on a sword for reparations," Brophy said.

He said other measures, such as an open debate about UA's slave past, headstones for unmarked slave graves, a university apology, and maybe a museum in one of the former slave quarters, would all be healthy for the school

"It's not like we don't have the buildings built with slave labor," Brophy said. "Having benefited from that labor, this institution has a moral duty to make amends." (source: Alabama Law Review)

enjz

ReplyDeleteenjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz

enjz