![[Last+Streetcar.jpg]](http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_jBentniQJ_E/Si6hcSGdGMI/AAAAAAAAAKE/3Z1jGX33rFU/s320/Last%2BStreetcar.jpg)

From the Washington Post Book Review "'The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans' by Lawrence N. Powell," reviewed by Jonathan Yardley, on 30 March 2012 -- “Long in the back of my mind was the thought of one day tackling a history of New Orleans,” Lawrence N. Powell writes, but Hurricane Katrina pushed him to turn possibility into reality. The calamitous storm of 2005 forced him “to think differently about the city,” offended as he was by “all those promiscuous statements about how my adopted hometown should be allowed to slide back into the primordial ooze.” People who knew little or nothing about New Orleans were asking: “Why rebuild a sinking metropolis on a site that shouldn’t have been selected in the first place?” Powell found the question “hurtful” but agreed that it “deserved a respectful answer.”

So now we have what Powell calls “a stab at an honest answer.” It is in fact a great deal more than that. Powell, who holds an endowed chair in history at Tulane University, has written in “The Accidental City” what should stand for years as the definitive history of New Orleans’s first century, the period that he regards as central to the city’s formation and its character. His study covers the time from its establishment in the famous southern crescent of the Mississippi River in the early 18th century to its sale by Napoleon to the United States, as part of the Louisiana Purchase, in 1803. Powell rounds out its century with a brief account of Andrew Jackson’s stunning victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, “a watershed in the young nation’s history . . . chiefly because the victory established once and for all that the United States was no longer a colony — not even in feeling, let alone in fact.”

The coming into being of New Orleans is a dramatic story but not an especially pretty one, populated as it is by rogues, scoundrels, opportunists, slavers and a vast congregation of ne’er-do-wells. Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, the young French Canadian who chose the site and presided over its early development, never will enjoy the saintly status that for generations has been bestowed on the founding fathers. Bienville, though both a street and a hotel in the French Quarter are named in his honor, is a most unlikely candidate for canonization, given that the vast Le Moyne clan was deep into cronyism and nepotism, and that he “accumulated enemies the way some people collect coins.” He was canny, not unduly scrupulous, but also “an intrepid commander, a tough bureaucratic infighter, and an even more astute Indian diplomatist,” this last being especially important as peaceful relations with nearby Indian tribes were essential.

Bienville came to the French colony in the Lower Mississippi Valley as an adventurer but stayed to become its leading citizen. France wanted to wean its citizens from their addiction to English tobacco and hoped to establish tobacco as a crop in the colony. What eventually became known as the Mississippi Company was established to that end, and a search was begun for the location of its “company town.” Bienville got in on the ground floor of this operation — he was as avaricious as he was ambitious — and in time rather arbitrarily chose the site in the crescent. There were difficulties galore — the chief one being the river itself, “powerful and unstable, hard to enter at its mouth, harder still to navigate, because of its currents” — and there were other prospective sites that may or may not have been more feasible, but Bienville stood firm:

“The site was dreadful. It was prone to flooding and infested with snakes and mosquitoes. Hurricanes battered it regularly. Pestilence visited the town almost as often. But New Orleans’s situation — its strategic location near the mouth of one of history’s great arteries of commerce — was superb. Before the construction of canals and especially of railroads enabled farmers, millers, and manufacturers in the Midwest to ship their products directly to the East, the rivers floated their crops, goods, and wares to the Atlantic Coast and points beyond. . . . Geographers and historians give Bienville a lot of credit for recognizing New Orleans’s stupendous situational advantages early on, notwithstanding the swampy drawbacks of the site itself. Yet, in fact, it took almost two decades for Bienville, and the French generally, to act on his inspired foresight.”

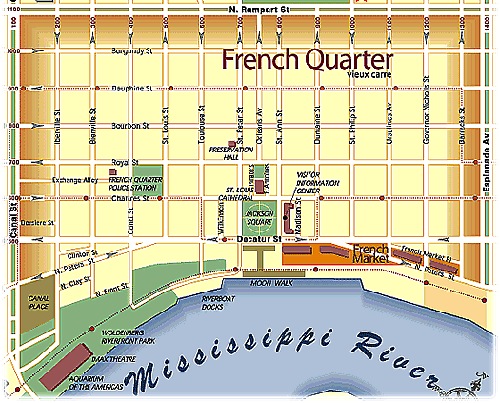

After all the squabbling and shilly-shallying, the real difficulties got underway. The French had in mind to design a city that was “almost a textbook example of the Enlightenment mania for balance, order, and clarity,” and indeed the checkerboard grid of the original Vieux Carre, or French Quarter, is still clearly visible today. But the French did not reckon with the populace of New Orleans, from the outset “famous for ‘excessive stubbornness,’ ” not least because it included an impressive number of “convicts, smugglers, and deserters.” The orderly settlement envisioned in Paris quickly degenerated into an economy “steeped in smuggling; in fact, it thrived on contraband trade to a degree that is still underestimated.” Powell writes: “All the town’s pillars of respectability — governors, commandants, members of the Superior Council, from Bienville on down — connived at and joined in the contraband trade. . . . Simply put, smuggling was Louisiana’s lifeline, and New Orleans’s as well.”

France finally threw up its hands and in 1762 turned over the colony to Spain, a process that took years and kept the city “squirming on tenterhooks.” When the Spanish did take over, they proved in some ways more benign rulers than their predecessors — their policy on the manumission of slaves bordered on the liberal — but essentially New Orleans was impervious to governance. For a long time some slaves there were allowed to earn money on their own and to congregate voluntarily. This was an essential contribution to New Orleans’s emergence as a genuinely multi-racial city, though of course then as now discrimination, and much worse, prevailed.

The situation was further complicated by the emergence of the Creole community, direct descendants of the 18th-century settlers, some of them European in ancestry but many others of mixed race. Powell’s account of New Orleans’s racial history is extensive; he is especially good on the subject of the black militias that formed during the Spanish rule and helped strengthen the city’s community of free blacks.

Spain’s rule ended in 1802, when Napoleon “bullied Spain into secretly retroceding Louisiana to France,” but soon enough he gave up on his American possessions and sold “more than 500,000 acres . . . all or part of fifteen future states,” to the United States. With the departure of Spain and the absorption into the new republic, along with the rise in sugar production in Louisiana, came the imposition of furiously repressive new slave codes eagerly sought by the Louisiana aristocracy. As Powell puts it, “Under the aegis of republican self-rule, in short, New Orleans’s slaveholding elite had finally achieved an indivisible sovereignty over slaves — an authority they had scarcely dared dream of while subjects of the Spanish crown.”

In this as in so much else, the history of New Orleans is steeped in irony, paradox and confusion. As Powell writes about a canal that was planned but never dug in 1719: “But this was how things went in New Orleans before New Orleans officially became New Orleans, and long afterward, too: solutions to foreseeable problems usually surfaced as afterthoughts. The improvisational style was characteristic of many frontier communities. Early New Orleans raised it to an organizational principle.” It has remained one ever since. (source: Washington Post)

No comments:

Post a Comment