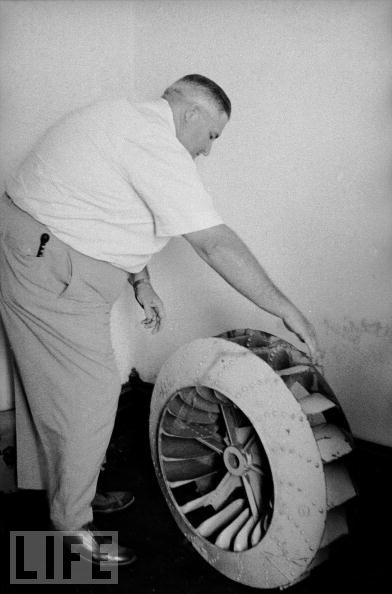

As reported by the New York Times, "The Ghosts of Emmett Till," by Richard Rubin, on 31 July 2005 -- We've known his story forever, it seems. Maybe that's because it's a tale so stark and powerful that it has assumed an air of timelessness, something almost mythical: Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black kid born and raised in Chicago, went down in August 1955 to visit some relatives in the hamlet of Money, Miss. One day, he walked into a country store there, Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market, and, on a dare, said something fresh to the white woman behind the counter -- 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the owner's wife -- or asked her for a date, or maybe wolf-whistled at her. A few nights later, her husband, Roy Bryant, and his half brother, J.W. Milam, yanked young Till out of bed and off into the dark Delta, where they beat, tortured and, ultimately, shot him in the head and pushed him into the Tallahatchie River. His body, though tied to a heavy cotton-gin fan with barbed wire, surfaced a few days later, whereupon Bryant and Milam were arrested and charged with murder.

Reporters from all over the country -- and even from abroad -- converged upon the little courthouse in Sumner, Miss., to witness the trial. The prosecution mounted an excellent case and went after the defendants with surprising vigor; the judge was eminently fair, refusing to allow race to become an issue in the proceedings, at least overtly. Nevertheless, the jury, 12 white men, acquitted the defendants after deliberating for just 67 minutes -- and only that long, one of them said afterward, because they stopped to have a soda pop in order to stretch things out and ''make it look good.'' Shortly thereafter, the killers, immune from further prosecution, met with and proudly confessed everything to William Bradford Huie, a journalist who published their story in Look magazine.

Yes, we know this story very well -- perhaps even too well. It has been like a burr in our national consciousness for 50 years now. From time to time it has flared up, inspiring commemorative outbursts of sorrow, anger and outrage, all of which ran their course quickly and then died down. But the latest flare-up, sparked by a pair of recent documentaries, ''The Murder of Emmett Till'' and ''The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till,'' has spread to the federal government: last year, the Department of Justice announced that it was opening a new investigation into the case. This spring [2005], Till's body was exhumed and autopsied for the first time. It has been reported that officials may be ready to submit a summary of their findings -- an ''exhaustive report,'' as one described it -- to the local district attorney in Mississippi by the end of this year. The only person in the Department of Justice who would comment on any aspect of the investigation was Jim Greenlee, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Mississippi, who would say only that its objective was ''to get the facts about what exactly happened that day and who might be culpable.''

I have spent a good bit of time trying to do the same thing, even though it's hard to see how I might have any kind of connection with the story of Emmett Till. I am a white man from the Northeast who is not a lawyer or an investigator or an activist; what's more, the whole thing happened a dozen years before I was born. But as is the case with so many other people, the story took fierce hold of me the first time I heard it, as a junior in college in 1987, and it has never let go. It drove me, after graduation, to take a job at The Greenwood Commonwealth, a daily newspaper in Greenwood, Miss., just nine miles from Money. There, I found myself surrounded by people who really were connected, in one way or another, with the case: jurors, defense lawyers, witnesses, the man who owned the gin fan. My boss, a decent man who was relatively progressive when it came to matters of race, nevertheless forbade me to interview any of them -- even to ask any of them about it casually -- during the year I worked for him.

In 1995, when I found myself back in the Delta to conduct interviews and cover a trial for what would eventually become a book about Mississippi, I took the opportunity to try to talk with the people I couldn't back when I lived there. Unfortunately, many of them had died in the interim, including Roy Bryant. (J.W. Milam died in 1980.) After a good bit of detective work, I managed to track down Carolyn Bryant, only to be told by a man who identified himself as her son that he would kill me if I ever tried to contact his mother. I laughed loudly into the phone, more out of surprise than amusement. ''I'm not joking,'' he said, sounding a bit surprised himself. ''Really, I'm not!''

There were others, though, who were willing to talk, were even quite obliging about it, which surprised me, because these were men who had rarely, if ever, been interviewed on the subject. You see, I wasn't interested in talking to Till's cousins and other members of the local black community, the people who had been there with him at the store, who had witnessed or heard tell of his abduction and had worried that they might be next. Those people had been interviewed many times already; I knew what they had to say, empathized with them, understood them. The people I wanted to interview were those with whom I couldn't empathize, those I didn't understand. I wanted to sit down with the men who were complicit in what I considered to be a second crime committed against Emmett Till -- the lawyers who defended his killers in court and the jurors who set them free. I wanted to ask: How could they do it? How did they feel about it now? And how had they lived with it for 40 years?

I talked to four of them. They're all dead now.

Ray Tribble is easy to spot in the photographs and newsreel footage of the trial: whereas 11 of the jurors appear to be staid middle-aged or elderly men, Tribble is wiry and young, in his 20's. Later he became an affluent man, a large landowner, president of the Leflore County Board of Supervisors. Whenever his name came up -- which it did fairly often, at least when I lived in Greenwood -- it was uttered with great respect. I was in town for six months before I learned that he had been on the Emmett Till jury.

Six years later, I called Tribble to see if he would talk to me about the trial. He didn't really want to, he said, but I was welcome to come over to his house and visit for a while. He might discuss it a bit, and he might not, but in any event, he didn't feel comfortable with my bringing a tape recorder, or even a note pad.

Tribble lived way out in the country, about five miles north of the crumbling building that had once been Bryant's Grocery. He met me on the front lawn and ushered me inside, where we talked a good while about everything, it seemed, but what I had gone there to discuss. Then, I recall, he suddenly offered, ''You want to know about that thing, do you?'' I did.

He had first suspected it might not be just another trial, he said, when reporters started showing up; then the camera trucks clogged the square, and the jury was sequestered, lodged in the upper floor of a local hotel. He recalled one member managed to bring a radio in so the men could listen to a prizefight. And then, without any emphasis at all, he added, ''There was one of 'em there liked to have hung that jury.'' One juror, he explained -- not him, but another man -- had voted twice to convict, before giving up and joining the majority.

I was stunned. I had always heard, and believed, that the jury's brief deliberation had been a mere formality. This news forced upon me a belated yet elementary epiphany: the Emmett Till jury was not a machine, an instrument of racism and segregation, a force of history. It was just like any other jury -- a body composed of 12 individuals. One of whom, apparently, was somewhat reluctant to commit an act that history has since ruled inevitable.

Tribble told me he couldn't recall which juror, but said it in a way that made me wonder if he truly couldn't remember or if he could but didn't care to say. I ran some names by him, but he would neither confirm nor deny any of them, and fearing that the conversation might soon be coming to an end, I changed the subject and posed the question I had wanted to ask him for six years: Why did he vote to acquit?

He explained, quite simply, that he had concurred with the defense team's core argument: that the body fished out of the Tallahatchie River was not that of Emmett Till -- who was, they claimed, still very much alive and hiding out in Chicago or Detroit or somewhere else up North -- but someone else's, a corpse planted there by the N.A.A.C.P. for the express purpose of stirring up a racial tornado that would tear through Sumner, and through all of Mississippi, and through the rest of the South, for that matter.

Ray Tribble wasn't stupid. He was a sharp, measured man who had worked hard and done well for himself and his community. How, I asked him, could he buy such an argument? Hadn't Emmett Till's own mother identified the body of her son? Hadn't that body been found wearing a ring bearing the initials LT, for Louis Till, the boy's dead father?

Tribble looked at me earnestly. That body, he told me, his voice assuming a didactic tone, ''had hair on its chest.'' And everybody knows, he continued, that ''blacks don't grow hair on their chest until they get to be about 30.''

The Bootstrapper

In 1955, Joseph Wilson Kellum was a lawyer in Sumner, Miss. In 1995, he was still a lawyer in Sumner, and still practicing out of the same office, across the street from the courtroom where Bryant and Milam were tried and acquitted. J.W. Kellum was their defense attorney.

He was actually one of five; it is said that the defendants hired every lawyer in Sumner so that the state would not be able to appoint any of them a special prosecutor on the case. Kellum gave one of two closing statements for the defense, during which he told the jurors that they were ''absolutely the custodians of American civilization'' and implored them, ''I want you to tell me where under God's shining sun is the land of the free and the home of the brave if you don't turn these boys loose -- your forefathers will absolutely turn over in their graves!''

Kellum was a 28-year-old grocery clerk who had never attended college when, in 1939, he took the state bar exam, passed it and immediately started a solo law practice. For more than 50 years his office was a plain, squat concrete structure bulging with messy piles of books and files and papers, unremarkable but for its proximity to the courthouse. We talked there for 90 minutes, and he never once grew defensive or refused to answer a question. At the start, he told me, he had regarded the defense of Bryant and Milam as ''just another case over the desk.'' Had he ever asked them if they killed Emmett Till?

''Yeah,'' he said, ''they denied that they had did it.''

I asked if he had believed them. ''Yeah, I believed them,'' he replied, ''just like I would if I was interrogating a client now. I would have no reason to think he's lying to me.''

I quoted his statement about the jurors' forefathers turning over in their graves if the defendants were convicted. What had he meant by that? ''Their forefathers, possibly, would not have ever convicted any white man for killing a black man,'' he explained. I asked Kellum if he'd had any misgivings about appealing to the jury's racial attitudes that way. ''No, not at the time,'' he replied.

''Did you feel the same way at the time?'' I asked.

''Not now,'' he said. He told me about a Vietnamese boy he sponsored in 1975, after the fall of Saigon. I restated the question. ''Put it this way,'' he said. ''I didn't feel that it was justifiable in killing an individual, regardless of what his color might be. I didn't think any white man had a right to kill an individual -- black individual -- like he was a dog.''

How, then, could he have so passionately implored the jury, in his closing argument, to rule in a way that would nullify those very values? ''I was trying to say something that would meet with -- where they would agree with me, you see. Because I was employed to defend those fellas. And I was going to defend them as much as I could and stay within the law. Those statements were not -- I received no admonition during the argument from the judge at all.''

''So you just looked at it as part of your job?''

''Part of the day's work,'' he said.

Did he now believe that Bryant and Milam had, in fact, murdered Till?

''I would have to see something,'' he said. ''But they told me they did not. They told the other lawyers that they did not. I have not seen anything where it was supposed to have been an admission of guilt on their part.''

If that statement were true, it would make him quite possibly the only man alive at the time who had not read or at least heard about Huie's Look article. But I didn't press him on it, didn't call him a liar. The strange thing is that, in my memory, I had always pressed J.W. Kellum hard, maybe even a bit too hard; for 10 years, I felt a bit guilty about how pointedly I had posed difficult questions to a rather genial octogenarian who had graciously invited me into his office and offered me as much of his time as I wanted. Today, though, when I read through the transcript of that conversation, I can't help feeling that I was too easy on the man. I guess we all make accommodations with the past.

The Aristocrat

It is not widely known, but shortly after they were acquitted, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam suffered a series of reversals. The family owned a string of small stores in the Delta; almost all of their customers were black, and most of them boycotted the stores, which soon closed. Local banks, with one exception, refused to lend money to Milam, who was also a farmer, to help him plant and harvest his crop. The one exception was the little Bank of Webb; Huie speculated that the bank came to Milam's rescue because John Wallace Whitten Jr., another member of the defense team, sat on its loan committee. According to Huie (who later paid the brothers for the film rights to their story), it was Whitten who brokered the Look interview, which took place in Whitten's small law office. Forty years later, Whitten sat down in that same office to discuss the trial with me.

Whitten was a most unlikely savior for two such men. A scion of one of the area's oldest and most prominent families, he went to college and law school at Ole Miss. After graduation, he shipped off to the war in Europe, where he rose to the rank of captain and was awarded a Bronze Star. When he returned home, J.J. Breland, the senior lawyer in town, asked Whitten to join his law firm. Such was the stature of the Whitten name that Breland, who was more than three decades older than Whitten, immediately renamed his firm Breland & Whitten.

Whitten was 76 and suffering from Parkinson's disease when we met in 1995, and though he was still practicing law, he often had difficulty speaking. Despite that -- and the fact that, as he told me later, his wife had ''fussed'' at him for agreeing to speak with me -- he was a gracious and open host, and like Kellum, never grew defensive or refused to answer a question.

One of his responsibilities before the trial, he told me, was to go down to Greenwood and meet with Dr. L.B. Otken, who examined the body after it was pulled from the Tallahatchie River. Otken, he recalled, had told him, ''This is a dead body, but it doesn't belong to that young man that they're looking for.'' Did he really believe that? ''I'm sure I did at one time,'' Whitten said. ''I'm sure he convinced me of it.'' Had his thinking since changed? ''Oh, yes,'' he said. ''I believe that it was the body of Till.''

I appreciated his candor, even as I suspected it was a bit incomplete. Or perhaps Whitten was merely choosing his words very carefully; when he said, ''I'm sure I did at one time,'' the natural interpretation is, ''I must have, or I never would have done what I did.'' But I doubt very much that a man like John Whitten could have actually believed such a dubious thing at any time; I imagine that he and the rest of the defense weren't really trying to sell that argument to the jurors so much as they were offering it to them as an instrument of plausible deniability should anyone question their judgment in the future. And now, like J.W. Kellum, he seemed to be engaging in a bit of historical revisionism.

And he clung to it, even when I read to him from an account of his closing argument that had been published in The Greenwood Commonwealth on Sept. 23, 1955:

There are people in the United States who want to destroy the way of life of Southern people. . . . There are people . . . who will go as far as necessary to commit any crime known to man to widen the gap between the white and colored people of the United States. They would not be above putting a rotting, stinking body in the river in the hope it would be identified as Emmett Till.

I asked him if he had really believed those things as he was saying them. He said yes, then surprised me by adding: ''And I suppose I would probably say I still believe it. I believe there were certain people who would profit by it.''

Whitten then revealed something else about himself: clients may have hired him for his old Delta name, but what they got in the bargain was a savvy lawyer who wanted to win and knew how to do it. ''That's one of the benefits of arguing where the prosecutor just has a circumstantial case,'' he said. ''If it's just circumstantial, you can go argue your own circumstances over his, and if they believe you, you win.''

I asked him if he thought the jury had reached the correct verdict. ''Under the circumstances, I don't know if correct would be the right word,'' he told me. ''But I think it was sustainable.'' Had he since come to believe the defendants guilty? ''I expect, yes,'' he said. ''If you had to put me down as -- if I had to say one way or the other what my belief was, it would be that the body was that of Till and he had been put in the river. These people either did it or knew of it.''

I raised the subject of his having helped get a loan for Milam -- who, like Whitten, was a veteran of World War II, and a highly decorated one at that -- after the trial. Huie had quoted Whitten as saying: ''Yes, I helped him. He was a good soldier. In a minefield at night, when other men were running and leaving you to do the killing, J.W. Milam stood with you. When a man like that comes to you and his kids are hungry, you don't turn him down.''

''Did you really feel that he was a good man?'' I asked.

''Yes, I did. Now, I don't say I felt like he was a man I wanted to know and be with every day. But I felt like he was honest. I felt like he was -- could be counted on to do things and look after his family. I never changed my mind about that.''

''Well, how is it possible that he did this, then?''

He was silent for a moment. ''I don't know,'' he said.

I asked him if he didn't see a conflict there: how could he believe both that Milam was a good man and that he was a murderer? ''Well, if that's what you're to judge by,'' he said. ''I don't know whether doing this means he's bad or not. I can't -- I'm sure I would have done differently, but I don't dismiss him in every respect because he made one mistake -- bad mistake, but his children are still -- he's still entitled to work and feed his children.''

He was clearly feeling uneasy now, and I could see that it was not merely with this line of questioning; his discomfort, I suspected, mirrored the way he had felt 40 years earlier when he had been called upon to defend men of a type he did not associate with, men who had committed a crime he no doubt considered distasteful, to say the least. People of John Whitten's background, his station, did not do such things, or embrace those who did. And yet, in killing Emmett Till, Milam and Bryant had drawn fire from the outside world, not just upon themselves and their crime, but upon their state and their region and nothing less than the entire Southern way of life. And John Whitten, as one of the chief beneficiaries of that way of life, had been called upon to defend it by defending them.

Adding to that burden must have been the knowledge that, in the process, he had become something of a spokesman for white resistance: his final entreaty to the jury was the most notorious utterance of the whole affair. ''I'm sure,'' Whitten told the jurors, that ''every last Anglo-Saxon one of you men in this jury has the courage to set these men free.''

''Why 'Anglo-Saxon?''' I asked him.

At first he offered something about Anglo-Saxons having ''a reputation for being a little harder against people who get out of line than do others,'' but he quickly set that aside and explained: ''You said 'Anglo-Saxon,' the jury would understand what you were talking about. You're talking about a white man.'' He added, making a pointed reference to another trial that at that very moment was also polarizing the country, ''I guess you could say I was playing the race card.''

And it occurred to me, right then, just how much the defense of O.J. Simpson owed to the defense of Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, and how little, in some ways, the country had changed in the past 40 years. The issue of race was still so potent that it could overwhelm evidence and hijack a jury, even when the case at hand was a brutal, savage murder. I found it interesting that Whitten made the connection; I wondered if anyone in that courtroom in Los Angeles had.

The Preacher

Sometimes, when you set out to find answers to what you believe are simple questions, what you actually end up with are more questions, the kind that are anything but simple. That's what happened to me during those four conversations. Especially the last one.

Howard Armstrong. In 1995, he was, aside from Ray Tribble, the only living juror. In 1955, he was a 36-year-old veteran of World War II, just like John Whitten, and was living in Enid, up in the northern stem of Tallahatchie County. Most of the other jurors, he said, were from other parts of the county, and he didn't know them. They might have known him by reputation: he was a lay minister, leader of the deacons at the Mount Pisgah Baptist Church. A few years later he would be ordained, and would serve as pastor to a number of congregations for the next 35 years, finally retiring at the age of 75, just a year before we met.

As with the others, I spoke to Armstrong on the phone first, and he invited me to come by and visit -- although, like Ray Tribble, he wasn't sure he wanted to talk about the trial. No one, he told me, had ever tried to interview him on the subject. ''Ain't a lot of people even know I served on that jury,'' he said.

He was living with his wife of 53 years, Janie, in a small, neat house that sat up on a rise off a dirt road. In 1955, he was a farmer who made ends meet by working nights at a heating and air-conditioning factory in Grenada, Miss., about 30 miles away. The first he had heard of the murder of Emmett Till, he told me, was when he received his jury summons. ''I didn't have time for much news,'' he explained, ''working night shift and farming during the day.''

I asked him how he had felt about serving. ''Really and truly,'' he told me, ''I can't remember how I felt about that. I reckon I felt the way I did about serving on any other jury. I wasn't crazy about serving on none of them. . . . I needed to be on my job and on the farm.'' When I pressed him to tell me what else he remembered, he responded: ''I don't want to pull it up. I want to leave it out there -- it's just best to leave things alone.''

''He just never did talk about that much,'' his wife, who was sitting next to him, explained.

I asked about the verdict. ''I didn't think that they presented the case to prove it,'' he said of the prosecutors. ''I understand that them folks was pretty much outlaws, but I didn't know that. I heard it years later.'' He was quiet for a moment. ''I still don't know.''

That truly surprised me. But he stood by it, insisting that the prosecution had not proven its case -- otherwise, he said, ''I'd never have voted the way I did.'' When I asked him what the jury deliberations had been like, he said, ''I'm sure there was a good bit of discussion. I do remember that there were at least three votes on that thing.'' He must have anticipated my next question, because he quickly added, ''And I voted to acquit all three times.''

I was disappointed; somehow, I had hoped he might have been that lone dissenter. I asked if he still believed they had reached the right verdict.

''I still think they were innocent,'' he said. ''I have no reason and no proof, and I don't judge people. I went and done my duty, left my duty where it was at and went on to other things.'' And no misgivings at all? ''I served to the best of my ability, under my prayer to God for guidance and wisdom. And I stand by my decision. . . . I still stand by it. I think I was right.''

''I guess you know that an awful lot of people disagreed.''

''I was surprised at all the fuss,'' he said. ''I thought we deliberated that thing, came back with a decision and that should be it.'' I asked him if racial tensions were sharpened there afterward. ''There wasn't as much tensions as there are now,'' he said.

''We've always had some good black friends,'' his wife added. ''Very good.''

''Go to Charleston,'' he told me, ''Talk to any of the blacks that was raised with me, and they'll tell you I was anything but a racist.''

And I found that statement more disturbing than anything that Ray Tribble, or J.W. Kellum, or John Whitten had said to me. Because I believed him. I believed that Howard Armstrong was not a racist. I felt I had gotten to the point where I could spot a racist of almost any type in almost any circumstance, and he was not one. And yet he had voted -- at least three times, by his own account -- to acquit two men who were clearly guilty of a horrific, racist crime.

.jpg)

I have spent a lot of time contemplating that conundrum over the past 10 years, and I have come to the conclusion that at least part of the problem is ours. We tend to think of racism, and racists, the way we think of most things -- in binary terms. Someone is either a racist or he isn't. If he is a racist, he does racist things; if he isn't, he doesn't. But of course it's much more complicated than that, and in the Mississippi of 1955 it was more complicated still. Today, we can look back and say that Howard Armstrong should have voted to convict Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam of murdering Emmett Till; but for him to buck the established order like that would have actually required him to make at least four courageous decisions. First, he would have had to decide that the established order, the system in which he had lived his entire life, was wrong. Second, he would have had to decide that it should change. Third, he would have had to decide that it could change. And finally, he would have had to decide that he himself should do something to change it.

Howard Armstrong never made it to that final step. Another juror apparently did, and managed to stay there through two votes before backing down. It is frustrating to me that I will probably never know who that other juror was, where he found the courage that got him that far and why, ultimately, he changed his mind. But it is even more frustrating to me to imagine that Howard Armstrong made it past Step 1 but got tripped up on 2 or 3.

I only wonder if it was frustrating for him, too. In 1995, sitting with him in his living room, I took his answers, his unwavering declarations that he had no regrets, at face value; today, I'm not so sure. Rereading my notes after 10 years, I can perceive a certain defensiveness in his words, an urge to keep the conversation short and narrow, perhaps cut off the next question before it could be asked. His insistence, like J.W. Kellum's, that this was just another trial feels flat now. And then there's his vacillation on the matter of whether or not the defendants were ''outlaws.'' Did he really believe, in both 1955 and 1995, that Bryant and Milam were innocent, and that he himself had done the right thing in voting to set them free? Or was this merely something he repeatedly told himself -- and others -- to get by? I do believe he was not a racist in 1995. But had he been one in 1955 and then grew, in subsequent decades, so ashamed of that fact that he did everything he could to defeat it in his own mind?

I don't know if Howard Armstrong could have answered those questions then, but I imagine he didn't want to try. It was easier on him, I'm sure, to believe that he had just forgotten all about it. ''I'm glad I can't remember those old days,'' he told me near the end of our visit. ''You hear so much about 'the good old days.' The good old days weren't so good.'' [source: The New York Times; Richard Rubin is the author of ''Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South.'' He is currently at work on a book about World War I.]

No comments:

Post a Comment