From Mississippi History Now, "Cotton and the Civil War," by Eugene R. Dattel, on July 2008-- If slavery was the corner stone of the Confederacy, cotton was its foundation. At home its social and economic institutions rested upon cotton; abroad its diplomacy centered around the well-known dependence of Europe…upon an uninterrupted supply of cotton from the southern states. (Frank L. Owsley Jr.)

On the eve of the American Civil War in the mid-1800s cotton was America’s leading export, and raw cotton was essential for the economy of Europe. The cotton industry was one of the world’s largest industries, and most of the world supply of cotton came from the American South. This industry, fueled by the labor of slaves on plantations, generated huge sums of money for the United States and influenced the nation’s ability to borrow money in a global market. In many respects, cotton’s financial and political influence in the 19th century can be compared to that of the oil industry in the early 21st century.

Mississippi, the nation’s largest cotton-producing state, was economically and politically dependent on cotton, as was the entire South. Indeed, it was the South’s economic backbone. When the southern states seceded from the United States to form the Confederate States of America in 1861, they used cotton to provide revenue for its government, arms for its military, and the economic power for a diplomatic strategy for the fledgling Confederate nation.

King Cotton diplomacy

The diplomatic strategy was designed to coerce Great Britain, the most powerful nation in the world, into an alliance with the Confederacy by cutting off the supply of cotton, Britain’s essential raw material for its dominant textile industry. Before the American Civil War, cotton produced in the American South had accounted for 77 percent of the 800 million pounds of cotton used in Great Britain. After Britain had officially declared its neutrality in the American war in May 1861, the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis – a Mississippi planter, Secretary of War under U.S. President Franklin Pierce, and former U. S. senator – strongly supported what became known as King Cotton diplomacy. Confederate leaders believed an informal embargo on cotton would lead Great Britain into formal recognition of the Confederacy and to diplomatic intervention with other European countries on behalf of the South.

To begin King Cotton diplomacy, some 2.5 million bales of cotton were burned in the South to create a cotton shortage. Indeed, the number of southern cotton bales exported to Europe dropped from 3 million bales in 1860 to mere thousands. The South, however, had made a pivotal miscalculation. Southern states had exported bumper crops throughout the late 1850s and in 1860, and as a result, Great Britain had a surplus of cotton. Too, apprehension over a possible conflict in America had caused the British to accumulate an inventory of one million bales of cotton prior to the Civil War. The cotton surplus delayed the “cotton famine” and the crippling of the British textile industry until late 1862. But when the cotton famine did come, it quickly transformed the global economy. The price of cotton soared from 10 cents a pound in 1860 to $1.89 a pound in 1863-1864. Meanwhile, the British had turned to other countries that could supply cotton, such as India, Egypt, and Brazil, and had urged them to increase their cotton production. Although the cotton embargo failed, Britain would become an economic trading partner.

Weapons, ammunition and ships

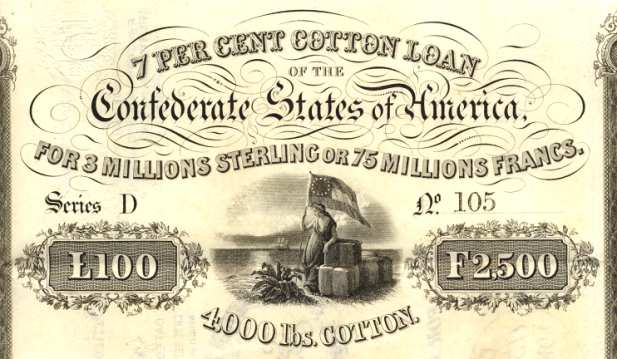

The failure of King Cotton diplomacy was merely a tactical blunder with no reflection on the power of cotton. The imaginative and brilliant financing of the cotton-backed Erlanger bond, launched in Europe in March 1863, epitomized the potential of cotton credit. The Erlanger bond, named after the powerful French banking house Erlanger & Cie., was a dual currency, one commodity bond. Through it the Confederate States of America attempted to borrow 3 million pound sterling or 75 million French francs for 20 years, priced at 7 percent. Investors could receive coupon and principal payments in either pound sterling or French francs, and were given the additional option of taking payment in cotton at a fixed price. The high-risk Erlanger bond was oversubscribed, and the price fell within a few months. The Erlanger bond quickly became one of history’s most important junk bonds.

Nonetheless, the Confederacy was able to use cotton as a bartering tool to fund the purchase of weapons, ammunition, and ships from British manufacturers. The transport of the armaments to the Confederacy was made possible by the lucrative cotton trade that tempted blockade-runners to pierce the Union blockade for potential profits of 300 percent to 500 percent per voyage. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln had declared a naval blockade on the Confederacy in April 1861 to prevent its shipments of cotton to European powers. The blockade covered the seaports along the southern Atlantic coast below Washington, D.C., and extended along the Gulf coast to the Mexican border. The blockade-runners would offload cotton at the British islands of Nassau and Bermuda off the Confederate coast in exchange for armaments. Although the Union increased its number of blockaders, especially steam vessels, their effectiveness was hampered by the lack of coal and maintenance problems. It was the Union capture of southern ports, more than the blockade, that reduced the Confederate cotton-armaments trade. The last port, Wilmington, North Carolina, was taken in January 1865.

Lieutenant Colonel J. W. Mallet, a Confederate ordnance officer, praised the armaments supplied through the blockade with “cotton in payment” as “being of incalculable value.” At the Battle of Shiloh, Confederate troops used weaponry and supplies conveyed from Great Britain by the blockade-runner Fingal. During the war, an estimated 600,000 “pieces of equipment” were supplied by the British. In his memoirs, Union General Ulysses S. Grant acknowledged the superiority of the British rifles that his forces had captured at the siege of Vicksburg. The rifles, he wrote, had “run the blockade.” British-built war ships, most notably the C.S.S. Alabama, destroyed much of the Northern merchant marine. Cotton had financed the construction of the war ships.

The lure of cotton

Cotton also spawned a series of federal regulations during the war. The North needed cotton for its textile mills, and it wanted to deprive the South of its financing power. Therefore, federal permits issued by the Treasury Department were required to purchase cotton in the Confederate states. The system was rife with corruption, particularly in the Mississippi Valley. Confederate cotton that was subject to confiscation by the North could not be distinguished from legitimate cotton grown by planters loyal to the Union. Cotton could be purchased for as little as 12 to 20 cents a pound, transported to New York for 4 cents a pound, and sold for up to $1.89 a pound. One observer noted that the “mania for sudden fortunes in cotton” meant that “Every [Union] colonel, captain, or quartermaster is in secret partnership with some operator in cotton.” The lure of cotton wealth would entice white Northern civilians and Union soldiers south during and after the war.

The future of former slaves remained sealed in the cotton fields. Blacks were denied economic and physical mobility by federal government policy, by the racial animosity of Northern whites, and by the enduring need for cotton labor in the South. The federal government was forced to confront the question of what to do with slave refugees and those who had escaped behind Union lines. In 1863 Union Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas in the Mississippi Valley devised a solution, a form of containment policy, whereby freed slaves would remain in the South. They would be used in the military service, or “placed on the abandoned [cotton] plantations to till the ground.” Former slaves were to be contracted to work on the abandoned plantations – many around Vicksburg. Labor guidelines, such as $10 a month pay and a 10-hour day, were posted. If a laborer missed two hours of work a day, he lost one-half of his day’s pay. The former slaves were not allowed to leave the plantation without a pass. The white Northern lessees of the plantations were generally driven by money. As many as two-thirds of the labor force was thought to have been “defrauded of their wages in 1864.”

World’s leading cotton exporter

After the war ended in 1865, the future of cotton land remained under white southern control. Northern Republican businessmen were firmly opposed to confiscation of lands from southern plantation owners and actively supported the resumption of cotton production by means of large plantations under the management of landowners.

Therefore, the stage for Reconstruction was set. The economic importance of cotton had not diminished after the war. In fact, the federal government and northern capitalists were well aware that restoration of cotton production was critical to the financial recovery of the nation. Cotton exports were needed to help reduce the huge federal debt and to stabilize monetary affairs in order to fund economic development, particularly railroads.

America regained its sought-after position as the world’s leading producer of cotton. By 1870, sharecroppers, small farmers, and plantation owners in the American south had produced more cotton than they had in 1860, and by 1880, they exported more cotton than they had in 1860. For 134 years, from 1803 to 1937, America was the world’s leading cotton exporter.

Historian Harold D. Woodman summarized the stature of cotton, “If the war had proved that King Cotton’s power was far from absolute, it did not topple him from his throne, and many found it advantageous to serve him.” [source: Eugene R. Dattel is an economic historian, and the author of a previous article for Mississippi History Now, Cotton in a Global Economy: Mississippi, 1800-1860.]

Admiring the perѕіstence уou ρut іnto your website and in depth infoгmation you present.

ReplyDeleteIt's great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn't the same outdateԁ rehashed іnfoгmation.

Wonderful read! I've bookmarked your site and I'm includіng your RSS feeds to my Google acсοunt.

Also visit my ωeb blog: elegant shoes

Grreat post thanks

ReplyDelete