From Slate, "The Transcontinental Travesty: What Gilded Age railroad-building frenzy reveals about American greed," by Donald Worster, on 6 June 2011 -- The corporate raider Gordon Gekko, in the 1987 film Wall Street, distilled the essential philosophy of the Reagan era, when we were supposed to get back to basic principles: "Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works." Although almost every ethical philosopher or religious leader of the past came out against greed as an emotion that distorts judgment and corrupts society, the Gekko-Reagan creed has usually been an easy sell in America. Running against that tradition, Richard White, in his new book Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America, doggedly persists in challenging the notion of greed as either rational or virtuous. He has a big job on his hands. No matter how many dot-com crashes or overleveraged credit debacles we go through, the core faith in greed as the engine of American greatness seems all but unshakable.

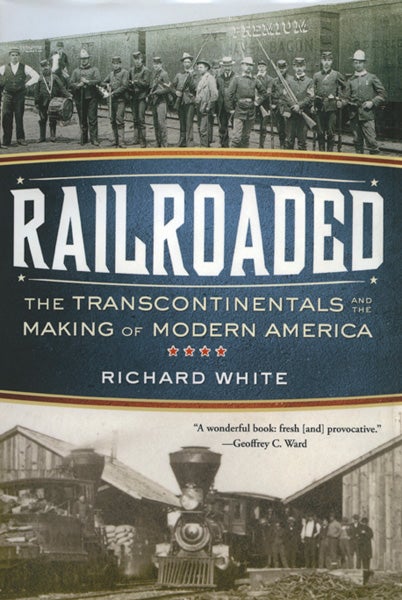

One legendary moment of greatness was the completion of the first transcontinental. There is a legend-making photo taken at Promontory Summit, Utah, May 1869, when the Union Pacific and Central Pacific joined tracks and reunited a war-divided people. After that came the Northern Pacific; the Great Northern; the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe; * and other lines that brought a transportation revolution to the West. White debunks the legend, arguing that the achievement was shoddy and chaotic and benefited the nation very little. The money that built those lines did not come from the railroad men themselves—Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Henry Villard, James J. Hill, and Thomas Scott. Instead, they persuaded Congress to lay out enormous subsidies.

The Union Pacific alone raked in $43 million in interest subsidies on federal loans, and railroads east and west of the Mississippi River received more than 131 million acres in free land. White explains that largesse as a result of political corruption. But then why did so many investors, including shrewd Germans and Brits, throw money into these enterprises as well? Not until the 20th century would there be enough white settlement and shipping traffic in the West to justify such investments. No rational need existed for decades, yet a railroad-building frenzy went on and on. The builders made a lot of money for themselves, but why did so many people give them so much capital?

Other government subsidies came in the form of stifling, with armed force, any resistance from Indians or any move on the part of immigrant laborers to try to make the railroads serve their needs. White describes in brilliant detail the infamous Pullman strike of 1893, when the government blatantly took the side of the corporations. "By and large, the western railroads remained what they had been before the strike—bloated, ill managed, heavily indebted, and corrupt. … Many were now wards of the federal courts, and all of them depended on the might of the federal government to control their own workers."

The dean of business historians Alfred Chandler Jr., in The Visible Hand(1977), described the 19th-century railroad corporation as the harbinger of order, rationality, and efficient organization. White scoffs at such an image. These corporations were made up of "divided, quarrelsome, petulant, arrogant, and often astonishingly inept men." And instead of the conventional leftist picture of a ruthless, soulless, but all-powerful business that crushed its opponents, the infamous Octopus of novelist Frank Norris, he finds "a group of fat men in an Octopus suit." They were morally challenged men, dripping with hypocrisy, mean-spirited, and grasping.

But White, who is a master of invective, describes them also as stupid and incompetent. Their only claim to genius was their ability "to find occasions for profit in their own ineptitude." Leland Stanford, for example, was well-known to his companions as dim-witted, careless, selfish, lazy, and yet filled with "immense self-regard." That tone of criticism appears all through the era. The Massachusetts railroad executive Charles Francis Adams, dismissed his fellow businessmen as creatures of "low instincts, … essentially unattractive and uninteresting." This is essentially White's view also, and he finds their success more than reprehensible; that such reptilian types ever gained so much power and wealth is bewildering. That their descendants still command so much authority is beyond understanding.

Richard White is a Thorstein Veblen for our times. Veblen (1857-1929) was an academic economist too radical for his own day. He and White share contempt for the business community; it was Veblen who invented such phrases as "conspicuous consumption" and "businesslike mismanagement." There are differences: White is a more engaging writer than Veblen, less given to windy circumlocutions, and he grounds his charges in deep and thorough research. Dripping with venom, this book is nonetheless a model of the historian's use of primary sources, narrative skill, and insightful reinterpretation of the Gilded Age. It is easily the best business history I have read, and it carries a weight of argument and evidence that cannot be denied. Another difference is that Veblen was dismissed by Stanford University for his "immorality" and unpopular views, while White is one of that university's most honored professors.

Unlike Veblen, White strongly identifies with the Indians who were dispossessed in part by the railroads and with the railroad workers who did the dirty and dangerous jobs for low pay and little freedom. White is emphatically on the side of those he calls the "anti-monopolists," contesting corporate authority, though he admits that most of them were racists who blamed immigrant Chinese workers for their precarious economic situation as much or more than they blamed the bosses. A society based on class and ethnic equality is closer to White's ideal than to Veblen's, who in turning away from the underdogs of society threw in with the technocrats, trained in rational analysis and management of modern technology and enterprise. In his book The Engineers and the Price System (1921), Veblen called for a "soviet of technicians" to run the railroads and factories of industrial America. That's not White's solution, but then what is his alternative to a society run by capitalists? What other choices did Americans have in the past or now? Whom should they trust?

The story of the transcontinentals, White writes, "is more than just a phase, the unruly youth of corporate capitalism." It represents the beginning of "a deeper mystery of modernity: how so many powerful and influential people are so ignorant and do so many things so badly and how the world still goes on." Why do the "unfit" seem always to triumph? I don't find his answer very clear or satisfactory. Leland Stanford and his fellow railroad men did not make America; it was America that made them, and it was foreign as much as domestic investors who gave them money. Voters and investors, workers and capitalists, all wanted to see the West "civilized" as quickly as possible. They dreamed of human empire over nature, and in that dreaming they didn't bother about balancing costs and benefits. The conquest was worth whatever it cost, in lost economic opportunity, in injustice, and in environmental destruction.

Call it greed if you like, but often it was not personal greed so much as it was desire to see whatever was wild and nonhuman brought under control. After the railroads came massive water-engineering projects (White does not discuss the role of the railroads in promoting that boondoggle that went on through the New Deal). Those likewise dramatically altered the ecology of the West, and they made no more economic sense than the railroads did. The water projects were easily sold to a public that wanted to see the world under "civilized" control. Until we confront more directly that rage for domination, we will never understand how men like the robber barons ever got into power. Or why they have left so many descendants today.

White ends his book with this judgment: "The issue is not whether railroads should have been built. The issue is whether they should have been built when and where they were built. And to these questions the answer seems no." But would a delay of a few decades have really mattered? Would it have brought a different group of people into power? Would the goal of civilizing the West have been more humane, environmentally restrained, or economically sensible? Perhaps. This book convinces me that the railroads helped create both "dumb growth and environmental catastrophe." A greater capacity for delay and restraint might have moderated both outcomes. But still we are left with the conundrum of modernity: Who is both smart and decent enough to be in charge of the enormous powers we have unleashed on the earth? I don't have much confidence in businessmen, but neither do I have confidence in engineers, workers, or college professors. Least of all do I have confidence in the state when it begins to subsidize and promote whatever entrepreneurs want to do.(source: Slate)

No comments:

Post a Comment