"The Forgotten: The Contraband of America and the Road to Freedom," by Eric Wills, from Preservation in the May/June 2011 issue -- Their names were Shepard Mallory, Frank Baker, and James Townsend. Little evidence documents their existence as enslaved field hands on a farm near Hampton, Va., aside from a few scribbled notes in an overseer's journal, listing them as property. But their lives were forever changed after the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. The three men were taken by their master to Sewell's Point, near present-day Norfolk, and put to work building an artillery battery for the Confederacy. Within days, they learned that their owner wanted to take them to North Carolina, where, separated from their families, they would be put to work constructing another rebel outpost.

They had a decision to make: Go with their master and aid the Confederate war effort? Or embark on a risky run for freedom by escaping to the Union stronghold at Fort Monroe? Mallory, Baker, and Townsend knew that if they were turned back at the fort, they would likely face whipping—or worse.

They also knew that if they somehow persuaded the Union soldiers to offer them refuge, their families in Hampton might be harmed in retribution. They didn't know that the consequences of their decision would mark a turning point in the war, long before the battles of Vicksburg or Gettysburg.

On the evening of May 23, as confederate sympathizers celebrated Virginia's decision to secede, the three men made their move, rowing a small boat across Hampton Roads to Fort Monroe, one of the only Union controlled outposts in the South. The fort's commander, Gen. Benjamin Butler, was no abolitionist—he had voted for Jefferson Davis at the 1860 Democratic National Convention. And Union policy on slavery was clear: President Abraham Lincoln maintained from the outset of hostilities that he had no intention of interfering with the "peculiar institution"; rather, the Union's aim was to crush the Southern rebellion.

Nevertheless, Butler realized the absurdity of honoring the Fugitive Slave Law, which dictated that he return the three runaways to their owner. They had been helping to construct a Confederate battery that threatened his fort. Why send them back and bolster that effort?

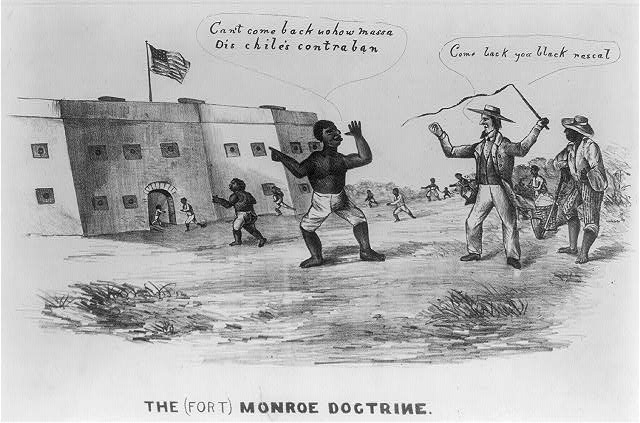

So the general struck upon a politically expedient solution: Because Virginia had seceded from the

Union, he argued, he no longer had a constitutional obligation to return the runaways. Rather, in keeping with military law governing war between nations, he would seize the three runaways as contraband—property to be used by the enemy against the Union.

Lincoln let the decision stand; Butler, after all, hadn't challenged the status of enslaved people as

property. Yet Mallory, Baker, and Townsend's escape and the general's clever gambit proved

momentous, the repercussions heralding the beginning of slavery's end. For when other enslaved

Africans Americans heard that three men had been granted refuge, they began flocking to Freedom's Fortress, as they called Fort Monroe. They came despite rebel rumors that the Yankees would eat them, sell them into slavery in Cuba, process them into fertilizer, or make them pull carts like oxen.

By war's end, approximately half a million formerly enslaved people and other African American

freedmen had sought protection behind Union lines. These "contraband," as they became known,

usually lived in camps hastily erected almost anywhere the army was stationed. The large number of runaways who flocked to Union lines belies the outdated and racist notion that enslaved African Americans simply waited for emancipation by singing hymns and strumming banjos; rather, they seized almost every chance to pursue their freedom, often risking death, and in so doing, helped make slavery a central issue of the Civil War.

"The most marginal people in American life, with no standing in civil or political society, end up being these consequential political activists who understand the war's events in much different ways than the educated policymakers," says Steven Hahn, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of A Nation Under Our Feet. (source: Preservation Magazine)

No comments:

Post a Comment