"Tecumseh's Vision" - In the spring of 1805, Tenskwatawa (actor Billy Merasty, Cree First Nation), a Shawnee, fell into a trance so deep that those around him believed he had died. When he finally stirred, the young prophet claimed to have met the Master of Life. He told those who crowded around that the Indians were in dire straits because they had adopted white culture and rejected traditional spiritual ways.

For several years, Tenskwatawa’s spiritual revival movement drew thousands of adherents from tribes across the Midwest. His elder brother, Tecumseh (actor Michael Greyeyes, Plains Cree), would harness the energies of that renewal to create an unprecedented military and political confederacy of often antagonistic tribes, all committed to stopping white westward expansion. The brothers came closer than anyone since to creating an Indian nation that would exist alongside and separate from the United States.

The dream of an independent Indian state may have died at the Battle of the Thames, when Tecumseh was killed fighting alongside his British allies, but the great Shawnee warrior would live on as a potent symbol of Native pride and pan-Indian identity. (PBS)

Which is Tecumseh?

Pictured above are two varying depictions of Tecumseh. The sketch at left depicts Tecumseh in traditional dress and was drawn in 1808. The 1848 painting at right by Benson Lossing was based on the former sketch but this version depicts Tecumseh in the uniform of a British general as was the popular (but untrue) belief of the time. Also note that Tecumseh is pictured sporting a “nose ring” which was usually not depicted in drawings of aboriginal peoples of this period.

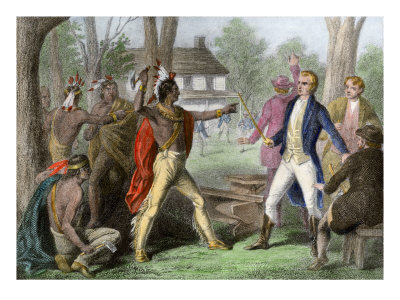

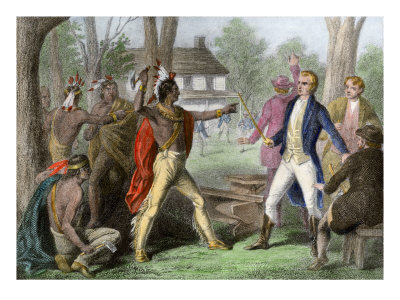

For nearly a decade after the battle of Fallen Timbers, there was relative peace in the Northwest. White settlers flooded into the area and the new American territories of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio were established. By 1810, some 200 000 Americans lived in Ohio alone. The Northwest nations had not forgotten their humiliation, however. They began to pay greater attention to an impressive young Shawnee named Tecumseh, who urged the creation of a single native confederacy stretching from the Canadian border to Spanish territory in Mexico that would be strong enough to resist the encroachment of the ‘Big Knives,’ as he termed the Americans. Tecumseh travelled ceaselessly, spreading his message to the Aboriginal peoples from the Great Lakes to the mouth of the Mississippi river. But while Tecumseh gave his listeners hope for the future he also advised them not to engage in warfare with the Americans until the time was right.

Not surprisingly the popularity of the charismatic Tecumseh worried American frontier officials. Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory met with Tecumseh twice in vain attempts to reduce the increasing tension between the Aboriginal peoples and White settlers, and he was both impressed and concerned:

The implicit obedience and respect which the followers of Tecumseh pay to him, is really astonishing, and more than any other circumstance bespeaks him one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions, and overturn the established order of things. If it were not for the vicinity of the United States, he would, perhaps, be the founder of an empire that would rival in glory Mexico or Peru. No difficulties deter him. For four years he has been in constant motion. You see him to-day on the Wabash, and in a short time hear of him on the shores of Lake Erie or Michigan, or on the banks of the Mississippi; and wherever he goes he makes an impression favorable to his purposes. He is now upon the last round to put a finishing stroke to his work.

In the autumn of 1811, Harrison decided to make a preemptive strike against this latest Confederacy. In early November, while Tecumseh was absent on a journey to the south, he moved a force of regulars and militia near the village of Tippecanoe (near modern Lafayette, Indiana) established by Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa or the Prophet. The Prophet was unable to restrain his warriors and sniping between sentries escalated into a pitched battle that was won by the Americans. Many of the defeated fled to the safety of Canada. When Tecumseh returned to the area early in 1812, he set out to rebuild his Confederacy and to placate American authorities. At the same time, he sought the assistance of British officers of the Indian Department who listened to him partly because they were convinced that war between Britain and the United States was at hand.

Although Tecumseh still counselled peace, he also believed that war was imminent and promised his Confederacy would ally itself with Britain in the forthcoming contest. He expressed to the Indian Department officers that ‘if their father the King should be in earnest and appear in sufficient force, they would hold fast by him.’ Tecumseh also stated that his followers were determined to defend their land and, although they did not expect Britain to engage in military operations, they did expect logistical support – ‘you will push forward towards us what may be necessary to supply our wants.’ For their part, the Indian Department cautioned the Confederacy not to attack until war was declared. As one officer put it, ‘Keep your eyes fixed on me; my tomahawk is now up; be you ready, but do not strike until I give the signal.’ Tecumseh agreed with this advice, but warned the British that:

"If we hear of the Big Knives coming towards our villages to speak peace, we will receive them, but if We hear of any of our people being hurt by them, or if they unprovokedly advance against us in a hostile manner, be assured we will defend ourselves like men. And if we hear of any of our people having been killed, We will immediately send to all the Nations on or towards the Mississippi, and all this Island will rise as one man."

Shawnee Chief Tecumseh Confronting William Henry Harrison in Indiana

Although Tecumseh still counselled peace, he also believed that war was imminent and promised his Confederacy would ally itself with Britain in the forthcoming contest. He expressed to the Indian Department officers that ‘if their father the King should be in earnest and appear in sufficient force, they would hold fast by him.’ Tecumseh also stated that his followers were determined to defend their land and, although they did not expect Britain to engage in military operations, they did expect logistical support – ‘you will push forward towards us what may be necessary to supply our wants.’ For their part, the Indian Department cautioned the Confederacy not to attack until war was declared. As one officer put it, ‘Keep your eyes fixed on me; my tomahawk is now up; be you ready, but do not strike until I give the signal.’ Tecumseh agreed with this advice, but warned the British that:

"If we hear of the Big Knives coming towards our villages to speak peace, we will receive them, but if We hear of any of our people being hurt by them, or if they unprovokedly advance against us in a hostile manner, be assured we will defend ourselves like men. And if we hear of any of our people having been killed, We will immediately send to all the Nations on or towards the Mississippi, and all this Island will rise as one man."

Throughout this period, the Indian Department had continued to provide annual gifts, including weapons and shot, to Aboriginal peoples in the United States and shelter for refugees from the struggles below the border. Such activities were regarded with great suspicion by American officials. Although some Aboriginal warriors residing in Canadian territory had participated in the fighting in the Ohio valley, their leaders in Canada encouraged the peaceful resolution of the differences between the Northwest nations and the Americans. The Seven Nations of Canada and the Iroquoian peoples in Upper Canada had seen enough conflict in the previous century and preferred to stay out of Anglo-American quarrels.

This desire to remain neutral became difficult, however, as Britain and the United States drifted toward war in the first decade of the 19th Century. The origins of the tensions between the two were, as usual, to be found in Europe. In 1793, revolutionary France had declared war on Britain, initiating a struggle that would ensue, with a brief intermission, for 23 years. Both countries had adopted restrictive maritime policies, forbidding the ships of neutral nations that traded with one belligerent from trading with the other. These measures severely curtailed the profits of American merchants. Since the British were supreme at sea, particularly after Nelson’s great naval victory at Trafalgar in 1805, American resentment was exacerbated by the Royal Navy’s penchant for stopping American vessels on the high seas and forcibly impressing their sailors, some who were British deserters, into British service. Many also suspected that Britain was promoting trouble in the Northwest by actively supporting the nations of Tecumseh’s Confederacy. Britain, pre-occupied with the war in Europe, seemed oblivious to American concerns. A few weeks after the battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, President James Madison of the United States, convinced that war was the only way that his country could resolve its grievances, decided to put the republic ‘in armour’ and prepare for hostilities against Britain. Given the overwhelming strength of the Royal Navy, the United States had only one practical military option: an attack on Canada. (source: Canadian National Defense History)

Mohawk Warrior from Tyendinaga, Autumn 1813

The warriors from the small Mohawk community at Tyendinaga near Kingston, although few in numbers, participated in much fighting during the War of 1812, seeing action at Sacketts Harbor and in the Niagara peninsula in 1813. Their most prominent service was rendered at the battle for Crysler’s

Farm in November,1813 where they played a role disproportional of their numbers. This warrior is

depicted as he may have appeared at Crysler’s Farm. (Painting by Ron Volstad [Canadian Department of National Defence])

Wow, Tecumseh died in 1813, and you posted this at 8:13. Get it? This helped me a lot thx!

ReplyDelete