The novel spans three continents and close to two centuries and is the first in a planned historical trilogy set in the 19th century.

Ghosh, a trained anthropologist and historian with a doctorate from Oxford University, spoke to the BBC's Soutik Biswas on the colonial opium trade.

Sea of Poppies is a historical novel. Is it the fact that the British were the world's biggest opium suppliers two centuries ago that led you into this story?

Ghosh: I should correct you. It was not two centuries ago. Under the British Raj, an enormous amount of opium was being exported out of India until the 1920s.

And no, the opium story was not really the trigger for the novel. What basically interested me when I started this book were the lives of the Indian indentured workers, especially those who left India from the Bihar region.

“ Before the British came, India was one of the world's great economies. For 200 years India dwindled and dwindled into almost nothing ”

But once I started researching into it, it was kind of inescapable - all the roads led back to opium. The indentured emigration [out of India] really started in the 1830s and that was [around the time of] the peak of the opium traffic. That decade culminated in the opium wars against China.

Also all the indentured workers at that time came from all the opium growing regions in the Benares and Ghazipur areas. So there was such an overlap there was no escaping opium.

When and how did you end up researching and learning more about the British opium trade out of India?

Ghosh: I was looking into it as I began writing the book about five years ago. Like most Indians, I had very little idea about opium.

I had no idea that India was the largest opium exporter for centuries. I had no idea that opium was essentially the commodity which financed the British Raj in India.

It is not a coincidence that 20 years after the opium trade stopped, the Raj more or less packed up its bags and left. India was not a paying proposition any longer.

What did you discover in the course of your research? How big was the trade?

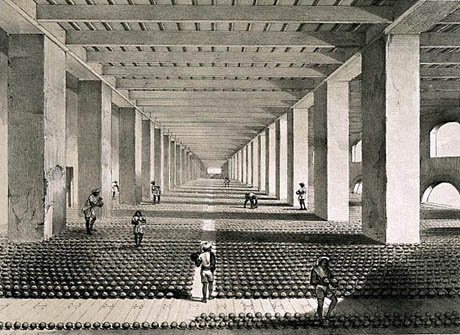

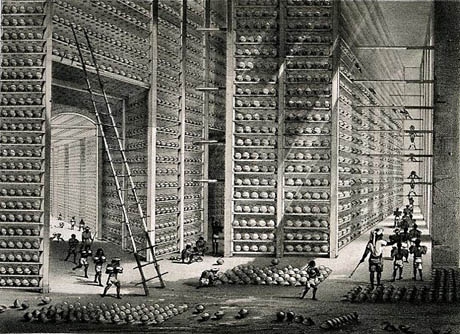

Ghosh: Opium steadily accounted for about 17-20% of Indian revenues. If you think in those terms, [the fact that] one single commodity accounted for such an enormous part of your economy is unbelievable, extraordinary.

In fact the revenues don't account for entire profits generated [out of opium trade] -there was shipping, there were so many ancillary industries around opium.

How and when did opium exports out of India to China begin?

Ghosh: The idea of exporting opium to China started with Warren Hastings (the first governor general of British India) in 1780.

The situation was eerily similar to [what is happening] today. There was a huge balance of payments problem in relation to China. China was exporting enormous amounts, but wasn't interested in importing any European goods. That was when Hastings came up with idea that the only way of balancing trade was to export opium to China.

In the 1780s he sent the first shipment of opium to China. It was a small shipment and they could hardly get rid of it. There wasn't much demand. [But], within 10 years, demand for opium increased by factors of magnitude. It was incredible - within a period of 10-30 years how much the opium trade spread and increased.

In the period that Hastings started exporting opium in the 1780s until about 1809-1810, most of the opium in India was grown in the Bengal presidency (in eastern India).

After that the Malwa region in western India began growing opium. Finally twice as much opium was growing in western India and there was a huge export from that region. What do you think the major princely states lived off?

What kind of human devastation did opium growing wreak on the Indians?

Ghosh: I can't say I have an accurate picture. Whether it was devastation or not we don't know. There is so little we know [about this aspect].

Some reformers were trying to stop the opium trade and we know from their petitions and letters that there was fair amount of resistance. There seem to have been a lot of difficulties for peasants - they were switching to an agricultural monoculture, and that was causing problems.

With so much poppy being grown, didn't local people get addicted to it?

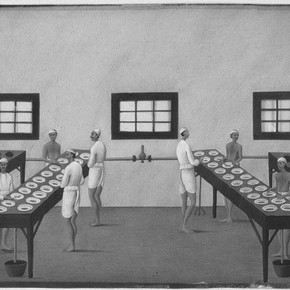

Ghosh: It happened. One of the curious things I was not aware of was that there are many different ways of consuming opium. One of the ways was to eat it in a bowl. This was somehow the commonest way of taking opium in India - either eating it or dissolving it in water.

East of India and eastwards through China there was a different way of consuming it which was by smoking it. That was very much more addictive.

It was not traditionally the case that people smoked opium in India. Opium also was a part of social life - it was offered during certain ceremonies. So it was a very complex picture.

If there was any direct damage to India, it lay in the disruption of the agricultural timetable. But the damage that was done to China was incalculable.

Both Indian and British history appear to have glossed over this part of colonial rule.

Ghosh: Absolutely. Opium was the fundamental undergirding of our economy for centuries. It is strange that [even] for someone like me who studied history and knew a fair amount about Indian history, I was completely unaware of it.

Why do you think that happened?

Ghosh: I think the reason is some sort of whitewashing of the past.

On the Indian side, there is a sort of shame, I suppose. Also, just a general unawareness. I mean how many people are aware that the Ghazipur opium factory [in India] continues to be one of the single largest opium producers in the world? It is without a doubt the largest legitimate opium factory in the world.

Don't you find it ironic that the tables have turned in a sense with Afghanistan becoming the world's biggest opium producer with most of it sold in the affluent West?

Ghosh: It is strange. But it's an irony in which no one can take any comfort. Opium is a destructive thing for anyone, anywhere.

And it remains a potent driver of economies, at least in a place like Afghanistan..

Ghosh: And, before that in Burma.

Sea of Poppies appears to be a scathing critique of British colonialism. Do you think colonialism has had a pretty easy ride in India and there is not enough examination of the extent of how it affected the country adversely?

Ghosh: It's such an ironic thing. Before the British came, India was one of the world's great economies. For 200 years India dwindled and dwindled into almost nothing. Fifty years after they left we have finally begun to reclaim our place in the world.

All the empirical facts show you that British rule was a disaster for India. Before the British came 25% of the world trade originated in India. By the time they left it was less than 1%.

Lot of Indians believe that the British built institutions, the police, bureaucracy.

Ghosh: I don't know what people think about when they say such things.

When they talk about [the British building] modern institutions it amazes me.

Was there no police force in India before the British came? Of course there was. There were darogas (policemen), there were chowkis (police stations). In fact the British took the word chowki and put it into English. So to say such things is absurd. (source: BBC)

British came to know that it's not blood stream or skin makes better human rather for human quality talent, intellect and other human quality is the measurement to have best bureaucracy and adminstration . British 1st saw that in China people are hired or recruited in higherarchy as per human qualities, talents, achievements, and built characters not by higherarchy of skin, blood or inheritances.

ReplyDelete