Introduction

Three issues at the fore of the Little Tokyo/Bronzeville story—the omnipotence of white racism, the specter of interethnic conflict, and the promise of interethnic coalitions—resonate throughout this book. In the pages that follow, I will demonstrate how and why Black and Japanese American communities came to occupy overlapping positions within the racial politics and geography of twentieth-century Los Angeles.

In the middle of 1943, Arthur Miley, an aide to Los Angeles County supervisor John Anson Ford, declared, “From all I heard it appears that Little Tokyo is going to be one big headache.” Conditions of squalor in the congested, segregated neighborhood in downtown Los Angeles alarmed public officials, social workers, and ethnic community leaders. Large families routinely occupied storefronts, warehouses, and churches never intended for human habitation. With others living in shacks, garages, and sheds, Miley warned that “permanent occupancy” in such facilities “would lead to juvenile and moral delinquency.” Inspectors from the city health department discovered one family living in an apartment so small that a set of twins was forced to sleep in dresser drawers. They later found a family of nine inhabiting one room with a five-foot ceiling and no windows. Fears of a public health catastrophe mounted. The chair of the Little Tokyo Committee of the Council of Social Agencies reported, “Garbage is scattered about and the rats are taking over.” Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron vowed to eliminate the neighborhood’s “deplorable overcrowding of as many as 16 adults and children in one room and extremely serious disease hazards.” Demanding more than “patchwork remedies,” the Communist Party’s local branch called for “the adoption and enforcement of a public policy” that would “make ‘Little Tokyos’ impossible.” Arthur Miley concluded that officials needed to take action “immediately on a large scale” or risk subjecting the city “to disease, epidemics, race riots and a general breaking down of the home front in this area.” But while public officials employed racially loaded language to characterize Little Tokyo, its residents at this time were not Japanese. Following the removal of Japanese Americans from Los Angeles during the early months of World War II, the ethnic enclave had shifted from being the center of the “Japanese problem” to serving as ground zero for the “Negro problem.” In May 1944, the Los Angeles Times declared that both residential and commercial structures formerly occupied by Japanese Americans were “now overflowing with thousands of Negro families from the Deep South.”1

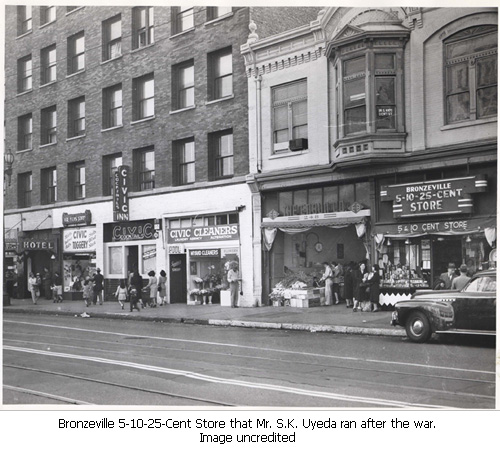

The wartime transformation of Little Tokyo into a community that African American entrepreneurs and community leaders dubbed Bronzeville most literally exemplifies the intersection of Black and Japanese American histories in twentieth-century Los Angeles. That African Americans would reside in a space previously carved out by Japanese Americans was no coincidence. Because the city’s white elites were preoccupied with building a business-friendly “open shop” town by subduing white labor unions, both Black and Japanese American pioneers arriving before the First World War had initially seen Los Angeles as a site of relative freedom and opportunity. As they simultaneously faced exclusion from segregated white neighborhoods, members of both groups lived in the same geographic niches during the first half of the twentieth century. Although the federal government allowed interned Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast in 1945, the sharp wartime rise in the Black population had overextended these small pockets of unrestricted housing. As the war neared its end, the question of how Little Tokyo’s recent arrivals would get along with the district’s prewar inhabitants thus became a major source of debate. Prominent white politicians and media outlets predicted violent turf battles between Black and Japanese Americans would erupt. Black and Japanese American activists, by contrast, envisioned a new level of interethnic political cooperation developing from heightened interaction between their communities. Those with only a conventional understanding of “race relations”—characterized by the bilateral interaction between a white majority and a Black minority—were ill-prepared to respond to these developments.

Three issues at the fore of the Little Tokyo/Bronzeville story—the omnipotence of white racism, the specter of interethnic conflict, and the promise of interethnic coalitions—resonate throughout this book. In the pages that follow, I will demonstrate how and why Black and Japanese American communities came to occupy overlapping positions within the racial politics and geography of twentieth-century Los Angeles.

To provide an overarching framework for this investigation, I trace the contours of the city’s multiracial hierarchy as it changed from the “white city” of the early twentieth century to the “world city” of the more recent past. Charting the rise of segregation, I posit that racism lay at the core of the 1920s real estate boom that made Los Angeles a major metropolis with a population surpassing 1 million. Although popular conceptions associate suburbanization with post–World War II American culture, the Southland’s decentralization took off three decades before the fifties sitcom Leave It to Beaver began filming in the San Fernando Valley. Unlike the old downtown elite, who championed industrial Los Angeles as the “Chicago of the West,” a rising bloc of developers and realtors drew on an idealized vision of the suburban neighborhood to market Southern California, especially the “Westside,” as a site for the preservation and renewal of whiteness. Viewing World War II as a turning point, I highlight the distinct but equally critical roles Black and Japanese Americans played in the rise and fall of integration. The war brought a new sense of unity and difference. As whites and Blacks came together around the notion of “interracial progress,” they did so primarily because anti-Japanese mobilization had created a heightened basis for national unity. Nevertheless, the postwar movement for integration brought about a reversal of Black and Japanese American fortunes. Whites increasingly exhibited either a passive or active acceptance of Japanese Americans but took greater measures to distance themselves both socially and geographically from Black (and Mexican) Americans. The ideological characterization of Japanese Americans as a “model minority” to be integrated served to stigmatize the others as “problem” minorities to be contained. But to the degree any postwar consensus existed, it was torn apart by the Watts Rebellion, signaling the demise of both integration and white hegemony. The book closes in the aftermath of Watts and at the dawn of the multicultural era, as African American mayor Tom Bradley and grassroots activists advanced and competing visions of Los Angeles as a multiethnic city within a global community.

This explication of urban political conditions provides context for closer scrutiny of the debates and struggles that took place within and between Black and Japanese American communities. The historical significance of these communities during this period is considerable. Los Angeles housed what were by far the largest concentrations of African Americans and Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Furthermore, while Blacks were of course the nation’s largest nonwhite minority, Japanese Americans comprised the bulk of all Asians living in the United States. Ultimately, however, the presence of these two groups transcended numbers. At distinct historic junctures, the city’s Black and Japanese American communities respectively served both as central targets of white supremacists and as models of racial progress.

My study couples two interconnected levels of analysis. At the most immediate level, this book is an account of how Black and Japanese Americans battled for housing, jobs, and political representation in Los Angeles as members of distinct ethnoracial groups. Drawing connections between seminal “Japanese” events like World War II internment and “Black” events like the civil rights movement, I compare and contrast the socioeconomic status and political standing of African Americans, Japanese Americans, and whites over the course of much of the twentieth century. My research further reveals how Black and Japanese Americans responded to instances of interethnic competition, as well as the degree to which they embraced opportunities for cooperation within oppositional social movements. As the narrative unfolds, it explains why Black and Japanese Americans faced common forms of racial discrimination prior to World War II but were subsequently thrust onto different historical paths.

On a second and broader level, this book is a case study of how race functions in a multiethnic context. By highlighting the triangular nature of relations between African Americans, Japanese Americans, and whites, my study provides multiple vantage points from which we may contemplate how diverse residents of Los Angeles saw their place within a multiracial order. Exploring the range of meanings these residents attached to both segregated and integrated communities, it offers a sense of how the multiethnic city was experienced on the ground. But it also shows how the ground itself shifted over the course of the twentieth century. What I mean by this is that the book’s central categories of analysis—“African American,” “Japanese American,” and “white”— were historically contingent constructs. Racial definitions varied over time and space in conjunction with demographic, economic, and political changes that resituated Los Angeles within a regional, national, and global order. Most obviously, a host of terms have been employed to identify these groups, many of which are now anachronistic and some of which have always been pejorative—“Negro,” “Black,” “colored,” “Japanese,” “Oriental,” “Caucasian,” as well as a host of vulgar epithets.

The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles, by Scott Kurashige

While racialized struggles over resources altered the status of groups and their relationship to power, they perhaps less obviously changed the rules by which racial politics operated. Beyond charting material relations between Black, Japanese, and white Americans, my research uncovers the ideological bases of these triangular relations. White elites played Black and Japanese Americans off against each other to solidify white hegemony. In turn, Black and Japanese Americans remained highly conscious of each other’s image and status as they negotiated and renegotiated their position within a multiracial social order. Differences in racialization became a basis for an opportunistic form of triangulation. By actively distancing themselves from the other group or passively accepting the distance created by white denigration of the other group, both Black and Japanese Americans were at times able to promote a sense of national belonging and greater white acceptance. Yet, if triangulation represented a form of capitulation to a hegemonic multiracial discourse, progressive activists of all races repeatedly sought to develop a counterhegemonic vision of multiracial solidarity.2

As much as this book is about what transpired in the past, it is equally concerned with how we think about the politics of race. Moving in step with the multiethnic rhythms of life and politics in Los Angeles requires interrogating and in some cases abandoning commonly held assumptions drawn from histories written in black and white. For the remainder of this introduction, I argue that putting Black/Japanese American relations at the center of the history of race, politics, and urban space complicates what we have come to know as the “urban crisis,” thereby challenging us to better come to terms with the origins of the “world city.”

Beyond the Biracial City

A focus on multiethnic Los Angeles history from the perspective of Black and Japanese Americans offers new ways of seeing and new modes of interpreting what historian Thomas Sugrue has called “the origins of the urban crisis.” Part of my story can be explained by the national patterns of urban segregation and inequality outlined by Sugrue in his influential 1996 book and expanded on by others in his wake. The Great Migration brought southern Blacks seeking political freedom and economic opportunity to the cities of the North and West, especially as the demand for their labor soared and Executive Order 8802 provided a measure to combat employment discrimination during World War II.

Although a wave of European immigrants had used industrial employment as a first step toward social assimilation and economic security, racism and deindustrialization ultimately denied African Americans the same form of advancement. Whites viewed workers of color as competitors for their jobs, and they feared that integration would destroy their property values and deteriorate their children’s schools. They deployed legal mechanisms, political pressure, grassroots mobilization, and racist violence to defend white privilege. Furthermore, postwar development, which was a joint product of private enterprise and public policy, magnified the scale of Black/white segregation and inequality. While new housing and employment opportunities concentrated in predominantly white suburbs, urban renewal efforts ravaged low-income residents and communities of color. Lastly, Cold War conservatism further dampened the prospects of urban Blacks by undermining the redistributive aspects of New Deal reform and repressing social democratic movements that advanced the principles of multiracial unity and “civil rights unionism.”3

At its core, the urban crisis narrative is an account of the failure of racial integration—a social movement and historical process whose fate has been inextricably bound to the construction of American national identity. First propelled by the optimistic liberal nationalism of World War II, the concept of racial integration prompted a heated public debate about national character. Social scientist Gunnar Myrdal’s assertion that the “Negro problem” was a “moral issue” striking at “the heart of the American” served as the opening salvo. Published in 1944, Myrdal’s monumental book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, argued that racism was the central defect of a nation built on the principles of liberty, democracy, and equality. He was convinced, however, that Americans—by which he essentially meant white Americans—were inherently moral and rational beings, who would resolve the glaring contradiction preventing their nation from attaining its highest ideals. What followed in actuality was a quarter century of sharp conflict proving that integration was a difficult if not impossible goal to achieve. Epitomizing the pessimism of the late 1960s was the “basic conclusion” of the Kerner Commission. Charged by the federal government to investigate social conditions in the aftermath of the wave of urban rebellions, the blue-ribbon panel proclaimed, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” The urban crisis narrative reflects the cumulative effort of an entire generation of scholars and political commentators to comprehend why things went so terribly wrong.4

While the urban crisis scholarship has enriched our understanding of the structural bases of poverty and racial oppression, it has yet to transcend the binary logic that has most informed scholarly and popular discourse on race in the United States. For example, the analysis Sugrue presents in The Origins of the Urban Crisis revolves around “the color line between black and white,” which he characterizes as “America’s most salient social division.” To be certain, my narrative recognizes that Black/white relations have played a critical role in the shaping of American politics. Like other major metropolitan areas, Los Angeles developed a predominantly Black ghetto that became socially and economically isolated from the more prosperous and predominantly white suburbs.

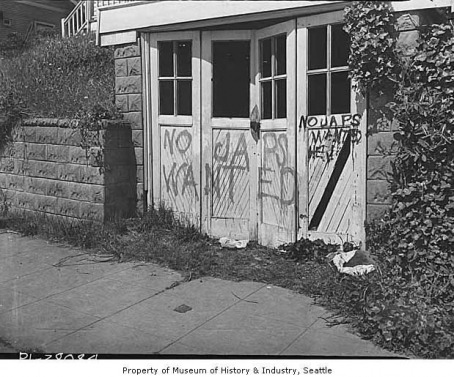

As frustration and anger mounted, mainstream politics did little to redress inner-city problems. Erupting in 1965, the Watts Rebellion marked one of the first major uprisings of the decade anywhere in the United States. Yet, in spite of these parallels, the established narrative stressing failure, repression, and decline cannot properly explain the history of racial politics in multiethnic Los Angeles. I maintain that it is impossible to grasp the predicament of African Americans or envision viable forms of African American political struggle without taking into account the many concerns that arise from multiracial dynamics. In Los Angeles, Black/white relations were neither autonomous nor so demonstrable as to make all other racial and ethnic relations residual. For instance, both anti-Black and anti-Japanese rhetoric and tactics proved integral to the architecture of segregation. To lure white migrants, suburban champions devised racial restrictive covenants to “protect” residential subdivisions from “invasions” by Black and Japanese Americans largely confined to the working-class Eastside neighborhoods like Little Tokyo and the Central Avenue district. What must also be stressed is that the communities Black and Japanese Americans created were never defined solely by their exclusion from white suburbia but rather through an array of interethnic and multi-ethnic relationships.5

It is my contention that the urban crisis has spawned an equally menacing epistemological crisis. Viewing integration as an aborted process, we have become transfixed with changes that did not occur at the expense of fully comprehending those that actually did. We need to complement our intricate knowledge of what was lost in the past with an awareness of what has created the new problems and possibilities we are now facing. My account is premised on the notion that the origins of the urban crisis overlapped with the origins of the economically vibrant and multicultural “world city” in postwar Los Angeles. To understand how these two seemingly opposing tendencies could be intertwined, we need to raise new questions about the history of segregation and integration: How and why did African Americans and the “Negro problem” become materially and ideologically linked to the “urban crisis”? How and why did Japanese Americans and the “model minority” become materially and ideologically linked to the rise of the “world city”? I submit that these were mutually constitutive processes that are best understood when situated within a multiracial context that recognizes the interconnection of local, national, and transnational dynamics. (source: Princeton)

ReplyDeleteيتمتع كل فرد من أفراد الأسرة بالسباحة والرش داخل المسبح في أيام الصيف الحارة. يعد الحفاظ على نظافة مياه حمام السباحة أمرًا مهمًا حتى تكون أنت وعائلتك في مأمن من الجراثيم والبكتيريا والفيروسات.

إذا لم تكن قد اعتنيت بأحواض السباحة من قبل ، فقد تبدو المهام صعبة بعض الشيء في البداية.

من خلال الحفاظ على نظافة حمام السباحة الخاص بك وإجراء الصيانة الدورية عليه ، يمكنك الحفاظ على المياه متوازنة وصافية للاستمتاع طوال الموسم.

شركة تنظيف مسابح بالدمام

تعتبر مشكلة تسرب المياه مشكلة مهمة ، فإذا أهمل ذلك سوف يسبب الكثير من الضرر سواء كان مادياً أو مادياً.

إصابات ، تسرب المياه

العيوب في المجرى المائي هي التي تسبب التجمع حول الأنابيب سواء في الأكواع أو الصنابير أو خزانات المياه أو حمامات السباحة ، إذا أدى الإهمال إلى تآكل الخرسانة وانهيار المبنى مما قد يتسبب في خسارة مادية أو خسارة في الأرواح.

شركة كشف تسربات المياة بالدمام