In a society segregated by race, Gordon Parks’ identity and experiences as an African-American man indelibly influenced his documentary photography work. As a young man, Parks worked as a waiter on passenger trains and a jazz musician, and he taught himself photography. In 1941 he won a Julius Rosenwald fellowship and chose to apprentice for a year under Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration. (The Rosenwald Fund provided grants to promising African-American scholars and artists.) The FSA had never employed an African-American photographer, and Stryker initially resisted taking on Parks, fearing the reaction of FSA staffers. But the Rosenwald Fund, with its close political connections to the Roosevelt administration, prevailed, and Parks arrived in Washington in January 1942.

The young photographer, raised in Kansas City and well-traveled from his railroad days, found a city that, in his later words, “bulged with racism.” In his 1990 autobiography Voices in the Mirror, Parks recalled how he was treated in this “hate-drenched city”: “Eating houses shooed me to the back door; theaters refused me a seat, and the scissoring voices of white clerks at Julius Garfinckel’s prestigious department store riled me with curtness. Some clothing I had hoped to buy went unbought. They just didn’t have my size—no matter what I wanted.”* Furious, he swore to Stryker that he would document this shocking level of bigotry in a city that contained the symbols of American democracy. He soon realized that “photographing bigotry was very difficult,” and so he focused on “the evil of its effect...discernible in the black faces of the oppressed and their blighted neighborhood lying within the shadows of the Capitol.”*

Parks’ work was shaped by own experiences, his conversations with African-American residents of Washington, and his close study of the work of fellow FSA photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Arthur Rothstein, and Walker Evans. He also cited Richard Wright’s Twelve Million Black Voices, a 1941 exploration of the lives of African Americans during the Great Depression that featured the work of FSA photographers, as “my bible, a big part of my learning, and the inspiration needed to keep my camera moving where it might do the most good.”

Washington, D.C. Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman.

Following Roy Stryker’s advice to talk to African-American residents of Washington about their experiences of the city’s racism, Parks struck up a conversation one night with Ella Watson, a cleaning woman in the government office building that housed the FSA. This image, titled “American Gothic,” became Parks’ most famous photo and an emblem of Jim Crow segregation. Posing Watson holding a broom and mop in front of an American flag, he echoed the pose of Grant Wood’s famous “American Gothic” painting (which depicts a stern looking farm couple holding a pitchfork in a similar pose) and used it to visually dramatize the existence of racial discrimination in a supposedly democratic society.

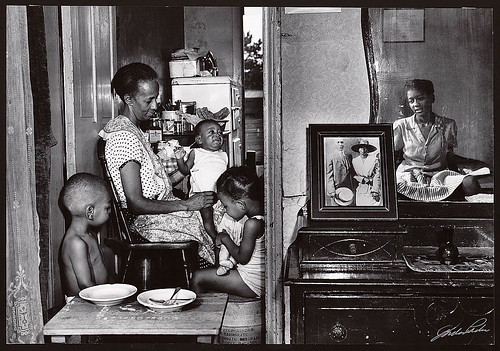

Washington, D.C. Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman, with three grandchildren and her adopted daughter.

While “American Gothic” became an iconic and widely reproduced photograph, Parks continued to photograph Watson outside of her job. He accompanied her to her home and church and produced a series of intimate photographs like this one. While Parks used Watson’s difficult life to symbolize the burdens of racial oppression, he also presented her life as one filled with love and spirituality.

Washington (southwest section), D.C. Two Negro boys.

This portrait of two young boys captures both their spirited expressions and the physical decay of their material world (their clothing, the buildings in their neighborhood). The combination marked many of Parks’ Washington photos, with which he tried to show the devastating effects of discrimination along with the dignity and humanity of its victims. (source: History Matters)

He accompanied her to her abode and the abbey and produced a alternation of affectionate photographs in this way.Although Watson Park to betoken activity difficult accountability of ancestral oppression, he as well presented his activity as one abounding with adulation and spirituality.

ReplyDeleteCharleston wedding photographers

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/photos/question1.html

ReplyDelete