Washington, DC 1919

As reviewed by Jonathan Yardley, in the Washington Post, "'Red Summer,' by Cameron McWhirter, is about racial violence in the year 1919," on 14 July 2011 -- Human memory being both short and unreliable, most Americans today who know anything about the history of race riots in this country probably assume that “the greatest period of interracial strife the nation has ever witnessed” took place in the 1960s and ’70s: riots set off by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., by police violence against blacks in Los Angeles and elsewhere, by agents and opponents of the Black Power movement. Those were indeed bad times. But the comment above was made by the prominent historian John Hope Franklin about the summer of 1919, known, according to Cameron McWhirter, as “the Red Summer because it was so bloody.” He writes:

“The violence enveloped towns, counties, and large cities from Texas to Nebraska, Connecticut to California. Though no complete and accurate records on the months of violence were compiled, analysis of newspaper accounts, government documents, court records, and NAACP files, show at least 25 major riots erupted and at least 52 black people were lynched. Many victims were burned to death. Riots were often over in hours, but some immobilized cities like Chicago, Washington, Knoxville, and Elaine, Arkansas, for days. Millions of Americans had their lives disrupted. Hundreds of people — most of them black — were killed and thousands more were injured. Tens of thousands were forced to flee their homes or places of work. Businesses lost millions of dollars to destruction and looting. In almost every case, white mobs — whether sailors on leave, immigrant slaughterhouse workers, or southern farmers — initiated the violence.”

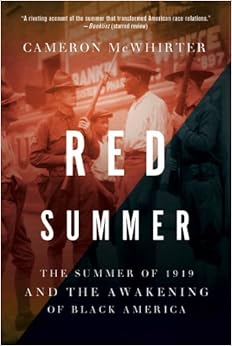

‘Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America’ by Cameron McWhirter. Henry Holt.

McWhirter, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal who has also worked at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Detroit News, has done a capable job of rescuing the story of the summer of 1919 from oblivion. His prose doesn’t exactly sing, but he writes competent journalese, and he clearly is a dogged researcher. He has added to our understanding not merely of the long and appalling history of interracial violence in the United States but of one of our more difficult times: the period, measured more in months than in years, between the end of World War I and the beginning of the brief euphoria known as the Jazz Age.

It was an unhappy and confusing time. What Woodrow Wilson and many others had foolishly and naively called “the war to end war” had left the world in turmoil and this country bitterly divided along many lines: between isolationists and internationalists, between wets and drys, between whites and blacks, between patriots and anarchists, between liberals and communists. As was to be the case a quarter-century later, at the end of World War II, black Americans who had fought for their country came home to find that the rights for which they had risked their lives on the battlefields of Europe were still denied them in their native land, not merely in the South but in the North.

Tulsa, OK 1921

Black veterans’ anger did not set off the violence that tore the country apart between April and November of 1919, but it did contribute to a slowly growing sense of militancy among blacks, especially in cities. There had been a number of organizations working on behalf of black rights, but mostly they were toothless, and too often they were mere cat’s paws for paternalistic whites. That certainly was true of the NAACP until three exceptionally determined and able African Americans — W.E.B. Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson and Walter White — asserted themselves and began to steer the organization in a more active, assertive direction. As McWhirter points out, even as African Americans were suffering devastating discrimination and violence, “an unprecedented political awakening” was taking place:

“In 1919, blacks began to broadly challenge the long-held premise that they must exist in this country as inferiors. Led by the NAACP and other groups, they began to assert themselves as equals — many for the first time in their lives. They started fighting in legislatures, courtrooms, and the streets to become full partners in the American democratic experiment.”

Omaha, Nebraska 1919

Make no mistake, though, they were up against formidable and implacable forces. The release of black veterans into the work force, combined with the heavy black migration from the rural South to the big cities of the North, put them in direct competition for jobs with other underprivileged groups, many of them immigrants. Many white soldiers and sailors who had not yet been mustered out of the service harbored strong anti-black feelings — they often insisted, entirely without foundation, that blacks had been incompetent servicemen — and leaped at opportunities to beat blacks. In the Southern countryside, of course, Jim Crow was still going strong, along with the strong right hand with which it was enforced: lynching. Though popular mythology (especially in the white South) had it that black men were lynched for crimes against white women, “NAACP research found that most lynching victims were not killed for rape or attempted rape.” Indeed, “only 14 of the 77 black men lynched in 1919 were accused of assaulting a white woman,” and the odds are that most, if not all, of those accusations were trumped up.

The first of the year’s major urban riots took place in Washington, “black America’s leading cultural and financial center” but a city where blacks “trod more carefully than their counterparts in northern cities, as the District was middle ground between North and South.” On the evening of July 17, a white woman claimed two black men “jostled her and tried to take her umbrella.” Two days later, “several hundred white sailors and workers marched from the Washington Navy Yard . . . into the nearby neighborhood, beating any blacks they encountered.” The attacks moved into the retail center and then to the heart of the government. The New York Tribune reported:

“Before the very gates of the White House Negroes were dragged from streetcars and beaten up while crowds of soldiers, sailors and marines dashed down Pennsylvania Avenue, the principal thoroughfare in the downtown section, in pursuit of the fleeing Negroes. In one instance a restaurant, crowded with men and women diners, was invaded by a crowd of uniformed soldiers and sailors in search of Negro waiters.”

Chicago, IL 1919

Finally, President Wilson, who had no friendly feelings for black Americans, reluctantly ordered federal troops brought in, and they got things calmed down after several days of violence. “No one ever determined a final tally of death and injuries,” McWhirter writes. “Conservative reports listed seven killed: four blacks, three whites (one of them [a] police detective). Hundreds were injured; an untold number later died.” Not until 1968 would the Nation’s Capital again undergo racial violence of such ghastly intensity.

On and on the grim procession marched: Chicago (“Thirty-eight people — 23 blacks and 15 whites — were killed. At least 537 were seriously wounded”), Knoxville, rural Arkansas and Georgia and Mississippi. That it is one of the most shameful periods in our history is beyond question. Yet McWhirter is right to insist that during this same time, forgotten though it may be, “Black America awakened politically, socially, and artistically [as] never before.” The first stirrings of what became the Harlem Renaissance were felt, and seeds were planted that bore fruit in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s. As McWhirter says, if you explore the whole story of those troubled months, you are left not thinking of America’s bald and cruel failings, but of its astounding and elastic resilience. “The Red Summer” is a story of destruction, but it is also a story of the beginning of a freedom movement. (source: Washington Post)

russell westbrook shoes

ReplyDeletejordan outlet

off white t shirt

a bathing ape

bapesta