From the New York Times, "A Piece of Slavery's Hidden Past," by Patricia Leigh Brown, 6 May 2003 -- Germantown, Kentucky -- Even now, slowed by a stroke and 70 years past his boyhood toiling in the fields as a tenant farmer, Isaac Lang Jr. can still recall the terrible secrets hidden inside the old tobacco barn.

"Dad told us never to go in there," Mr. Lang, 84, recalled, sitting up in his bed in a nursing home here. "He said, `Boys, I'm going to tell you the truth. It's all right to play around that barn, but don't go inside.' He said it just wasn't right. That it was pitiful. He never did tell us why."

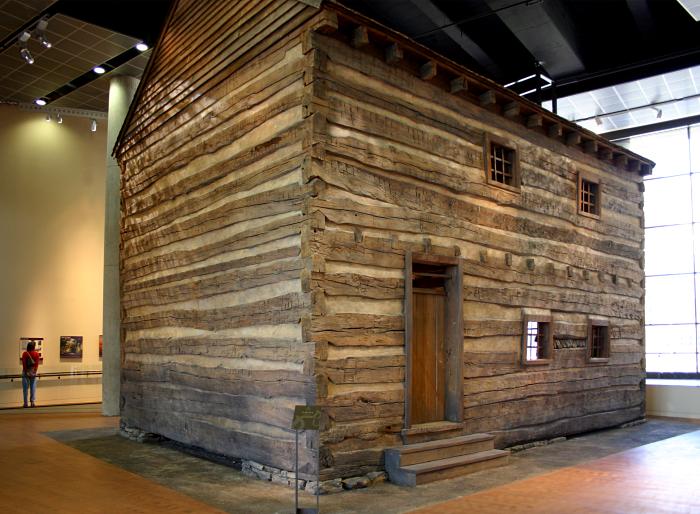

The building resembled the hundreds of long, low tobacco barns with rusting roofs that mark these winsome rolling hills along the Ohio River, except for a log structure concealed inside. Its windows were fitted with thick, crisscrossed wrought-iron bars ordered by Capt. John W. Anderson, a Kentucky slave trader.

In the forced westward migration of slaves in the years after 1790, historians say, Captain Anderson held an unknown number of African-Americans in the log house, which has recently been identified as the only known surviving rural slave jail.

For years, the slave jail, or holding pen, was encased and largely concealed within the tobacco barn, a later addition that screened it from the elements and ensured its survival. It was the stuff of lore, a public secret. Now in storage, its logs awaiting reconstruction, this environment of confinement will take its place in a museum dedicated to freedom, as the centerpiece of the $110 million National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

With artifacts from the slave era difficult to find and authenticate, and counterfeit shackles and slave identification tags swirling through eBay, the survival of the holding pen and its subsequent identification by historians and curators is a landmark in the material culture of slavery.

The insidious byways travelled by the traders and their slaves — rivers, oceans and roads — were served by a transcontinental network of holding pens, jails and yards built to warehouse and secure human cargo in transit. Among the few slave jails that have survived is one in the basement of 1315 Duke St. in Alexandria, Va., once the headquarters of Franklin & Armfield, among the country's largest slave trading companies. It is now a National Historic Landmark.

"That the slave pen still exists is miraculous," said John Michael Vlach, a professor of American studies and anthropology at George Washington University and the author of "Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery". "Slavery used up artifacts the way it used up people."

Forks of the Road, Natchez, MS

The movement to preserve vestiges of the internal slave trade is relatively recent. For example, with a $200,000 grant from the state Department of Archives and History, the city of Natchez, Miss., is trying to buy a quarter-acre section of the Forks of the Road, the second-largest market in the South, where roughly 1,000 slaves were sold a year, and transfer it to the National Park Service. An empty tavern and a parking lot are now at the site.

In a historic part of Lexington, Ky., known as Cheapside, once home to the state's leading slave market, markers honor Kentucky's vice presidents and Confederate heroes but do not mention the area's slave roots. Doris Wilkinson, a professor of sociology at the University of Kentucky, calls such omission "psychological concealment."

The Underground Railroad museum in Cincinnati is spending about $1 million on the slave jail, including disassembly and reconstruction. Next summer, when the museum opens, its 450,000 or so expected visitors will be able to walk through the holding pen and touch its walls.

"We're just beginning to remember," said Carl B. Westmoreland, a senior adviser and curator at the museum who has spent the past three and a half years uncovering the story of the slave jail. "There is a hidden history right below the surface, part of the unspoken vocabulary of the American historic landscape.

"It's nothing but a pile of logs," Mr. Westmoreland said. "Yet it is everything."

The jail languished for years as the barn around it slowly collapsed. In its dark attic lay a row of wrought-iron rings — five have survived — through which a central chain ran. Men were tethered on either side of the chain.

"It was a slave ship turned upside down," said Mr. Westmoreland, a trustee emeritus of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and himself the great-grandson of slaves.

The jail's original chimney faced the Ohio River, the boundary between slavery and freedom and the same fickle water to which Captain Anderson, who is buried 100 yards from where the jail stood, marched his slave coffles. It was an eight-mile trek down the Walton Pike to the landing at Dover, Ky., where they would board flatboats for a perilous 1,150-mile journey: Dover to Covington, Covington to Louisville, Louisville to Henderson, Henderson to Smithland, Smithland to Memphis, Memphis to Vicksburg, Miss., and on to the infamous Natchez slave market.

The vague outline of the barn's foundation is still imprinted in the alfalfa fields owned by Raymond Evers, 72, a retired Cincinnati steel contractor, and his wife, Mary, 75. They purchased the 280-acre farm and what they heard referred to as a "jail cell" in 1976. Mr. Evers spends weekends on the farm, growing alfalfa, corn and soybeans. He used the barn to store machinery and would occasionally unearth chains while plowing.

Mrs. Evers grew up in nearby Minerva and Maysville. In 1998, when the couple learned of plans for an Underground Railroad museum in Cincinnati, they asked museum officials to look inside their barn.

"It was something I'd read about — past tense," Mr. Westmoreland said. "It was something that used to exist — past tense."

The Everses gave the structure to the museum in exchange for a new barn. Then Mr. Westmoreland and historians, curators and archaeologists set about to determine whether the stories of a slave jail were merely folklore.

What they knew was that Mason County, and nearby Maysville in particular, had been a hemp and tobacco center and a mecca for slaveholders from Virginia and Maryland wanting to sell slaves into the deep South. In the last decade of the 18th century, the geography of slavery, which was largely confined to the Eastern seaboard and the Appalachians, shifted profoundly, crossing the easternmost Blue Ridge mountains and expanding into the Shenandoah Valley, Kentucky and Tennessee. Surplus slave labor in Virginia, the result of depleted soil and crop failure, made it relatively easy for Kentucky pioneers to purchase black slaves at favorable prices.

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and cotton planters' insatiable thirst for labor set in motion the forced westward deportation of slaves, most of them on foot. It was an event, the historian Ira Berlin wrote in his recent book, "Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves," that would tear families apart and displace more than a million people, "dwarfing the transatlantic slave trade that had carried Africans to the mainland."

There is as yet no known photograph or obituary of Captain Anderson, who died in July 1834 at age 41, according to his tombstone. In contrast to the antebellum stereotypes of slave traders as coarse and ill-bred characters "with a whiskey-tinctured nose, cold hard-looking eyes, a dirty tobacco-stained mouth and shabby dress," as one writer put it, they were often respected members of society. In Kentucky, they included Stephen Chenoweth, tax commissioner in Jefferson County, and Littleberry P. Crenshaw, a minister in Louisville.

Captain Anderson left an extensive paper trail of business dealings and legal disputes that described his slave trading. By piecing together information from estate inventories, court records, tax receipts and newspaper advertisements, historians have begun to assemble the story of Captain Anderson and his slave jail.

The first breakthrough was a Mason County probate document referring to a "jailhouse" on the property. Pen Bogert, a historical researcher in Louisville, discovered in the Adams County, Miss., courthouse copies of 1832-1833 tax receipts signed by a John W. Anderson for the sale of blacks. And in 1833, Captain Anderson offered a reward in a Maysville newspaper for the capture of four runaway slaves. Among them was "Carter, aged 25 years, about five feet four inches high, very bright mulatto, bush head; very stout, heavy made, and stammers when interrogated; full round face; he professes to be a shoemaker and rough carpenter."

At the time of his death, researchers say, Captain Anderson had become wealthy enough to invest in a silver-trimmed saddle and 42 thoroughbreds. He owned 37 slaves, far more than he typically claimed at tax time.

Research indicated that Captain Anderson converted a plain log building into a slave jail. Over the past few years, archaeologists have unearthed about 6,000 artifacts, including crockery, tools and kitchen utensils. As the building was being dismantled last fall, they discovered a log on the second floor, beside the rings, bearing the stamp of J. W. Anderson.

But the decision to move the holding pen from Kentucky to Ohio was controversial locally.

"By the time the public found out about it it was a done deal," said Alicestyne Adams, an assistant professor at Georgetown College in Kentucky and the director of the Kentucky Underground Railroad Research Institute. But the priority was preservation, she said.

"African-Americans have become used to having other people tell our stories," Professor Adams said. "Having an artifact that speaks to the magnitude of what occurred, and where it occurred, is extremely important."

In and around Mason County, some people wanted it to stay.

"It's part of the history of the area, but not the pretty part," said Caroline R. Miller, an English teacher in Germantown who has done extensive research on local court documents pertaining to slavery.

But many residents, Ms. Miller said, would prefer to be identified with the heroes of the underground railroad like Arnold Gragston, who was born a slave on Walton Pike and began rowing slaves to freedom in Ripley, Ohio, in 1859.

"There is a fear of being stigmatized," she said of the ambivalence. "It's not easy to learn that the history of where you live is more than unpleasant."

The green hills in and around the Everses' farm are dotted with white porticoed homes, but the original cookhouses and slave quarters out back remain hidden from public view and await historical reckoning.

"They bring up very painful memories," said James Oliver Horton, a professor of American studies and history at George Washington University who has been an adviser to historic sites like Monticello. "So even though they're out there, we don't want to find them."

Nonetheless, landscapes have memories. Carol Yates Bennett, 66, who grew up in Maysville, remembers her great-grandmother's story of a slave mother so bereft at her forced separation from her daughter, who was being sold downriver, that she cut off her hand in despair.

Ms. Bennett went to visit the jail on the Everses' farm before it was dismantled. "You just sensed the presence all around you," she said. "It felt like hallowed ground." (source: The New York Times)

No comments:

Post a Comment