From the New York Times Sunday Book Review, "'Imperial Reckoning' and 'Histories of the Hanged': White Man's Bungle," by Daniel Bergner, on 30 January 2005 -- In a war-ravaged town in Sierra Leone a few years ago, I listened as five men debated the idea of recolonization, which many of their countrymen favored. They sat in a derelict shed, the office of a building contractor who'd lost all his equipment to rampaging soldiers. He was lucky to be alive and unmutilated; factions in the civil war had cut off the hands of civilians, then let them live as the ultimate message of terror. Amid the ruin of their nation, only one of the five men objected to the idea. ''We had segregation, right over there,'' he said, pointing toward the desolate grounds of a secondary school, his voice rising in outrage. ''We couldn't go to that school!'' To which the contractor, white-haired and old enough to have spent his childhood under British rule, said, ''At least there was school for Africans.''

The men spoke during extreme times in their country; their desperation had reached this pitch after 10 years of anarchy. But despair pervades the continent. ''The average African,'' Moeletsi Mbeki, deputy chairman of the South African Institute of International Affairs and brother of South Africa's president, declared recently, ''is poorer than during the age of colonialism.'' Yet for anyone tempted, even fleetingly, to look to the past for solutions to Africa's problems, two new books, ''Imperial Reckoning,'' by Caroline Elkins, and ''Histories of the Hanged,'' by David Anderson, give warning.

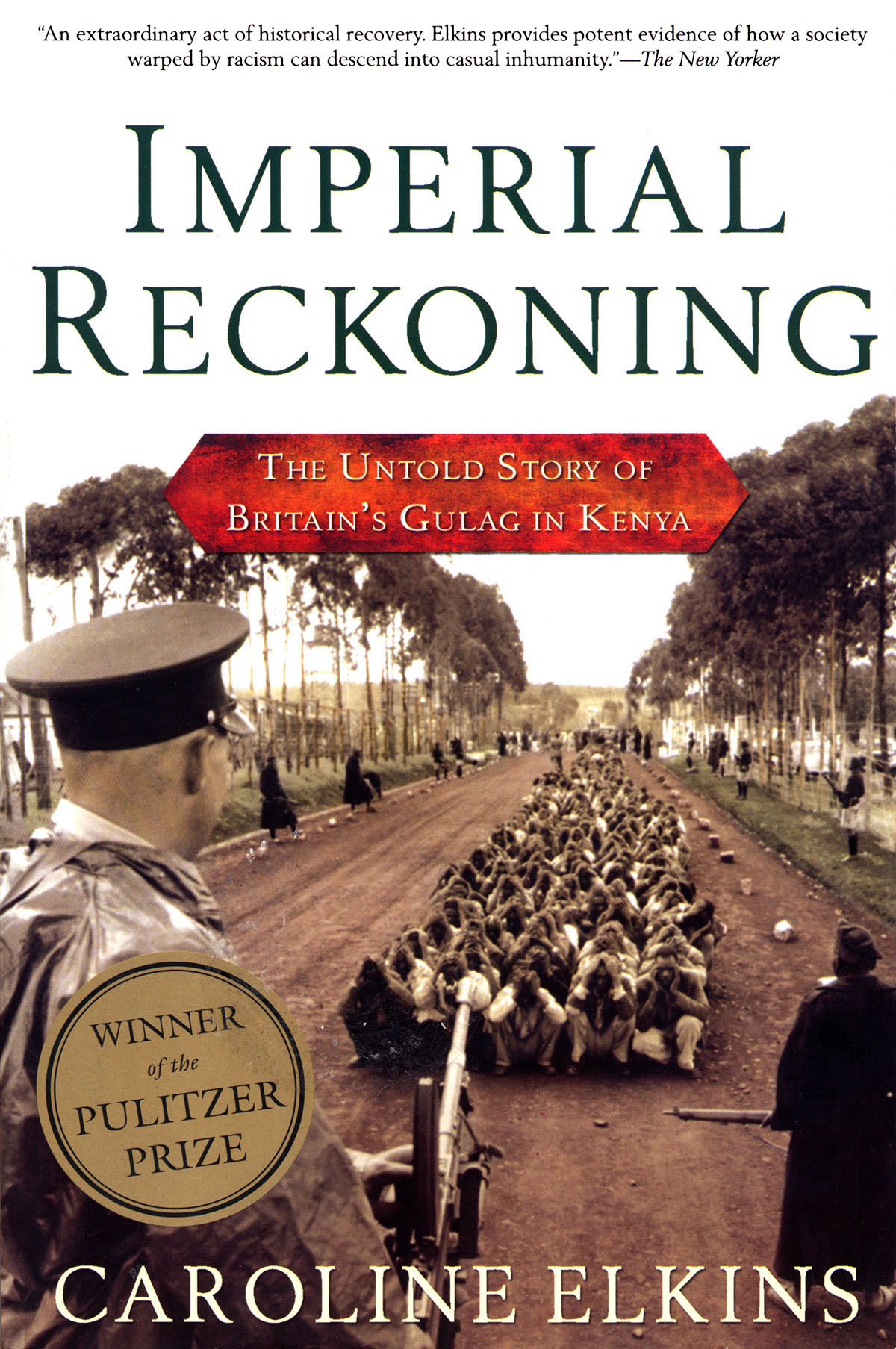

Focusing on the final decade of British rule in Kenya (ending in 1963), both writers evoke a period when, especially in Elkins's view, the colonial pretense of civilizing the dark continent gave way to the savagery of imperial self-preservation. Some 40,000 whites lived in Kenya by the early 1950's, drawn by promises of long leases on fertile land and native labor at low wages. ''Whatever his background,'' Anderson, a lecturer in African Studies at Oxford, writes, ''every white man who disembarked from the boat at Mombasa became an instant aristocrat.'' But by midcentury, many of the natives, particularly those of the Kikuyu tribe, refused to play their assigned role. The Kikuyu had been put off their most arable land by white farmers. They, like other Kenyan tribes, had been banished to ethnic reserves too small to sustain them. They were forced to carry passbooks as they searched for work from the governing race. In 1952, stirred partly by their displacement and partly by British efforts to prohibit traditional Kikuyu customs, a Kikuyu secret society, the Mau Mau, launched a rebellion, attacking white-owned farms and brutally killing perhaps a hundred whites and 1,800 of their African supporters. In retaliation, the British carried out a campaign that, Elkins suggests, amounted to genocide.

Anderson's book, meant as a kind of requiem for the ''as yet unacknowledged martyrs of the rebel cause: the 1,090 men who went to the gallows as convicted Mau Mau terrorists,'' never manages to render a vivid martyr. Examples of colonial judicial corruption and hypocrisy are thoroughly explored, but little room is left for character. Elkins, a history professor at Harvard, also neglects individual portraits, but she develops an unforgettable catalog of atrocities and mass killing perpetrated by the British. ''Imperial Reckoning'' is an important and excruciating record; it will shock even those who think they have assumed the worst about Europe's era of control in Africa. Nearly the entire Kikuyu population of 1.5 million was, by Elkins's calculation, herded by the British into various gulags. Elkins, who assembled her indictment through archives, letters and interviews with survivors and colonists, tells of a settler who would burn the skin off Mau Mau suspects or force them to eat their own testicles as methods of interrogation. She quotes a survivor recalling a torment evocative of Abu Ghraib: lines of Kikuyu detainees ordered to strip naked and embrace each other randomly, and a woman committing suicide after being forced into the arms of her son-in-law. She quotes an anonymous settler telling her, ''Never knew a Kuke had so many brains until we cracked open a few heads.'' Her method is relentless; page after page, chapter after chapter, the horrors accumulate.

Yet for all its power, ''Imperial Reckoning'' is not as compelling as it should be. With so much evidence of atrocity, Elkins often forgoes complexity and careful analysis. Not only are the colonists barbaric in their treatment of the Kikuyu, but, as she has it, they are basically barbarous in private as well, maintaining ''an absolutely hedonistic lifestyle, filled with sex, drugs, drink and dance.'' More important, there is the case that Elkins apparently wishes to make -- for genocide. ''Mau Mau,'' she writes, ''became for many whites in Kenya, and for many Kikuyu loyalists as well, what the Armenians had been to the Turks . . . and the Jews to the Nazis. As with any incipient genocide, the logic was all too easy to follow.'' According to the official statistics, the British killed 11,503 Mau Mau adherents. By contrast, Elkins estimates that ''somewhere between 130,000 and 300,000 Kikuyu are unaccounted for.'' She reaches her figures by reviewing colonial censuses taken in 1948 and 1962; she compares the increase in the Kikuyu population to the larger increases in three other Kenyan tribes. It's a fragile means to support her case, partly because we're left wondering whether the other tribes also grew more swiftly than the Kikuyu during earlier periods.

Unfortunately, Elkins's prosecutorial zeal in a sense precludes a true ''imperial reckoning.'' For British rule brought crucial benefits that persist -- among them modern education and a degree of infrastructure -- as well as violent oppression to its subjects. A thorough reckoning would provide, by way of paradox, not only a more deeply insightful but a more deeply wrenching work of imperial history.(source: New York Times Sunday Book Review)

Unfortunately, Elkins's prosecutorial zeal in a sense precludes a true ''imperial reckoning.'' For British rule brought crucial benefits that persist -- among them modern education and a degree of infrastructure -- as well as violent oppression to its subjects. A thorough reckoning would provide, by way of paradox, not only a more deeply insightful but a more deeply wrenching work of imperial history.(source: New York Times Sunday Book Review)

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteGiày là một trong những thời trang không thể thiếu, đặc biệt đối với những chàng trai chân ngắn thì lựa chọn đôi giày phù hợp rất quan trọng. Bạn có thể tham khảo cách lựa chọn qua bài viết

ReplyDeletenam chân ngăn nên mang giày nào. hoặc có thể tham khảo

cách chọn giày cho phái mạnh giúp bạn lựa chọn được những sản phẩm thích hợp nhất.

Hướng dẫn cách bảo vệ giày đi mưa giúp bạn bảo vệ đôi giày của bạn được tốt nhất.

Bài viết chia sẽ Cách đeo đồng hồ đẹp và quý phái giúp bạn lựa chọn cho mình những chiếc đồng hồ có thể tôn lên nét đẹp riêng cho bạn. Ngoài ra, chúng tôi còn chuyên cung cấp dây da dùng cho đồng hồ dây da nữ với giá rẻ và chất lượng tốt nhất trên thị trường hiện nay. Tìm hiểu chi tiết về thương hiệu đồng hồ nổi tiếng trên thế giới

Nguyên nhân bàn làm việc hòa phát được nhiều người lựa chọn là gì khi trên thị trường có nhiều thương hiệu sản xuất noi that van phong gia re khác nhau.

ReplyDeleteNên lựa chọn ban van phong gia re có kích thước như thế nào là phù hợp đúng chuẩn

ReplyDeleteI like this post. quite informative blog. Keep blogging.. thanks

fear of god outlet

ReplyDeleteyeezy outlet

bape sta

jordan outlet

cheap jordans