Santa Claus and His Works

Artist: Thomas Nast

From the New York Times, "On December 25, 1866, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon about Santa Claus and Christmas," by Robert C. Kennedy (2001) -- This multi-framed illustration of “Santa Claus and His Works” was artist Thomas Nast’s first major depiction of Santa Claus in Harper’s Weekly (appearing in the postdated December 29, 1866 issue). Although other artists of the period sketched Santa Claus, Nast stands apart from the rest for his role in creating and popularizing the modern image of the Christmas figure. He contributed 33 Christmas drawings to Harper’s Weekly from 1863 through 1886, and Santa is seen or referenced in all but one. Nast’s full-page illustration of Santa Claus in 1881 quickly attained status akin to an official portrait, and is still widely reproduced today. Before Nast, different regions, ethnic groups, and artists in the United States presented Santa Claus in various ways. A sketch in Harper’s Weekly from 1858 shows a beardless Santa whose sleigh is pulled by a turkey. Nast was instrumental in standardizing and nationalizing the image of a jolly, kind, and portly Santa in a red, fur-trimmed suit delivering toys from his North Pole workshop. This was accomplished through his work in the pages of Harper’s Weekly, his contributions to other publications, and by Christmas-card merchants in the 1870s and 1880s who relied heavily upon his portraiture.

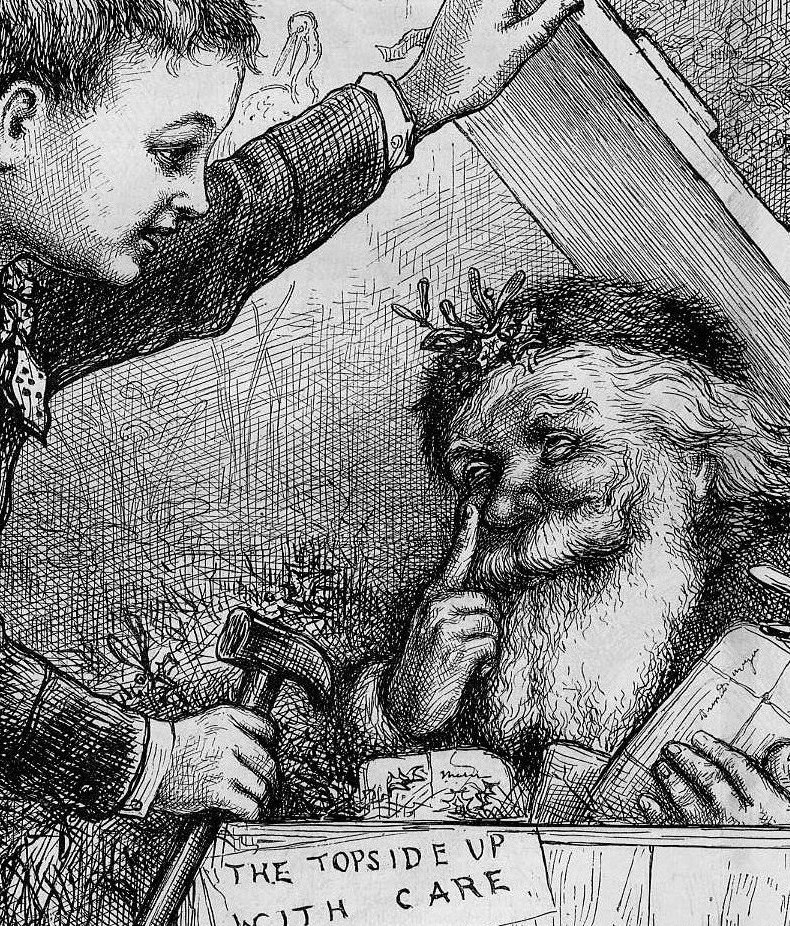

In the featured “Santa and His Works,” Nast adapts characteristics from his German heritage (he was born in Bavaria) and from Clement Clark Moore’s famous 1822 poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” (commonly known as “Twas the Night Before Christmas”), but the artist adds other aspects developed from his own creative mind and talented pen. The effect is to unveil much of the mystery behind Santa Claus by presenting a more complete account of his life, mission, and home. Instead of depicting him merely delivering gifts, the entire process of his work is detailed from the preparation to the execution to the recovery. The centerpiece is what children hope for: Santa stuffing stockings hung on the fireplace, as toys lie on the floor. He is plump, white-bearded, red-nosed, dressed all in fur, carries the sack of a peddler (evoking earlier lore of Santa as a peddler), and is still the short elf of Moore’s poetic version (here, Santa needs a chair to reach the mantle).

Along the sides, Nast adds parallel circular insets. To fulfill Santa’s traditional task of rewarding nice children and punishing naughty children, Santa uses a telescope to locate good children (upper-left), and records the behavior of children in an enormous account book (upper-right). On the center-left, he is seen in his workshop carefully crafting toys by hand (as opposed to the increasing reliance on factory production in America). On the center-right, he is taking a well-deserved post-Christmas rest in a rocking chair placed before a fireplace, as he holds a meerschaum pipe popular among Germans, Dutch, and their American descendents. On the lower-left, the diminutive Santa uses a ladder to decorate the Christmas tree (another German tradition), and on the lower-right, sews doll clothing by hand (rather than using a sewing machine). Three years later, in 1869, “Santa and His Works” was included in a new publication of Moore’s poem illustrated by Nast. At that time, Santa’s suit was changed to the red color for which it has thereafter been associated.

The origin of Santa’s home at the North Pole is uncertain, but in “Santa and His Works” Nast may have been the first illustrator to so identify the locale. (An 1857 illustration in Harper’s Weekly shows Santa preparing to leave a snowy but unnamed homeland.) In the late 1840s and the 1850s a series of expeditions to the Arctic captured public attention, and the area began to be discussed as the home of the elusive Santa Claus. Year-round the North Pole had the snow that was becoming associated in the popular image with Christmas (the American publishers of magazines, books, and cards carrying Christmas illustrations were headquartered in the snowy Northeast). Furthermore, the North Pole's geographic isolation permitted the jolly old elf to work without interruption, and the region’s independence from all nations allowed Santa to be a symbol of universal good will. The reference to the North Pole in the featured cartoon is on the curving border in the upper-right and reads “Santa Claussville, N. P.” The linkage of symbol and place was obviously common enough by 1866 that Nast realized he could simply abbreviate “North Pole.”

While setting the national standard, Nast’s own depiction of Santa Claus changed over the years. He began his almost-annual contribution of Christmas illustrations when he joined the staff of Harper’s Weekly in 1862 during the Civil War. His first Santa (in the postdated January 3, 1863 issue) is a small elf distributing Christmas presents to Union soldiers in camp. Santa dangles by the neck a comical jumping jack identified in accompanying text as Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president. There was no doubt in Nast’s illustration whose side Santa favors in the war. Besides the military context, the cartoon is set off from later ones in that the gift giving is for adults, not children (except for the drummer boys). The other two Christmas illustrations of Nast’s published during the Civil War emphasize family scenes, with Santa relegated to the background.

From 1866-1871, Nast continued to elaborate upon the image of Santa Claus portrayed in “Santa and His Works.” As in the featured cartoon, he also emphasized during this period Santa’s disciplinary role in judging whether the behavior of children during the past year warranted Christmas rewards or punishment. In an 1870 cartoon, Santa surprises two naughty children by jumping out as a jack-in-the-box clutching a switch for spanking. In 1871, Santa sits at his desk reading letter from parents chronicling their children’s good and bad acts, with the “letters from naughty children’s parents” far outnumbering the “letters from good children’s parents.” It is probably not coincidental that Nast was at that time the father of several young children (the eldest, Julia, was 9 years old in 1871). Whatever the reason, the cartoons helped revive the idea of Santa as reinforcing parental discipline, a notion that had waned since the publication of Moore’s poem in which Santa brought a “happy Christmas to all.”

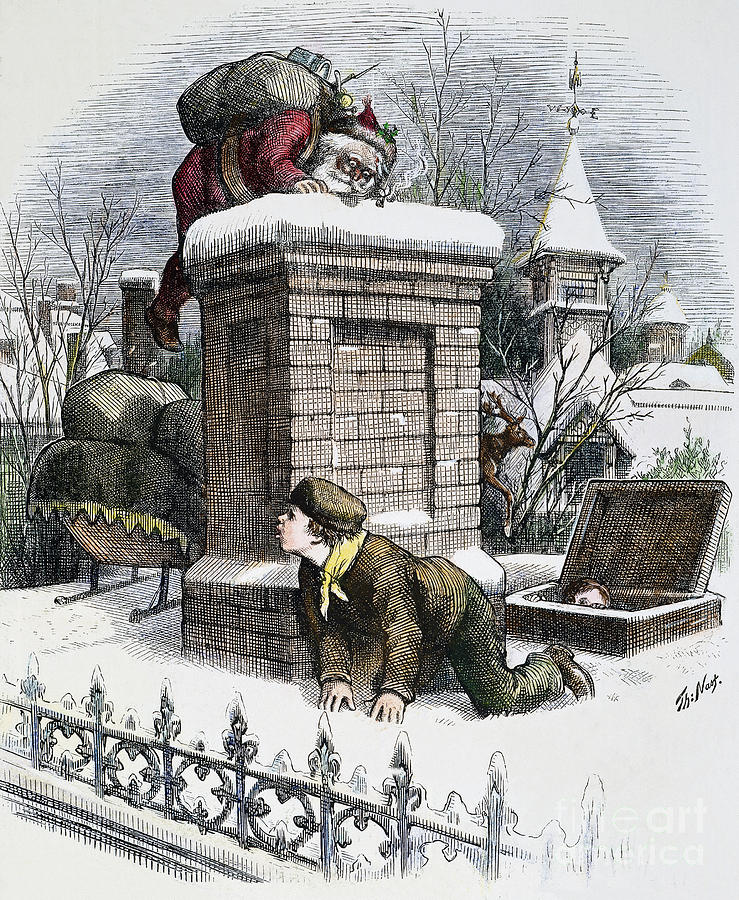

Through the rest of the 1870s, Nast’s Santa Claus was no longer the disciplinarian, but, instead, played a cat-and-mouse game with children in which he tried not to be seen and they tried to catch him in the act of delivering presents. Again, the illustrations likely reflected the situation in Nast’s home, where he loved to wrap presents and celebrate the season, but at a time when his children had become old enough to try to find the gifts and nab the gift-giver. In “Santa Waiting for Children to Get to Sleep” (1874), Santa is forced to delay on a rooftop because children in the house below are still awake. A related poem blames the late-night hours of the family on the use of gas lighting in homes.

As Nast’s own children entered and left their teen years, knowing that Santa was really their father, the artist’s illustrations finally showed direct communication and interaction between Santa Claus and the pictured children. In a postdated January 1879 issue, a girl drops a letter to Santa in a mailbox (the first time the artist depicted a letter from a child to Santa), and in December 1884, Santa and a girl are able to speak with each other by using a relatively new invention, the telephone. In the January 1879 issue, another Nast cartoon portrays Santa Claus in the midst of a group of gleeful children who he embraces affectionately. Santa is now recognized as part of the family, whose shared love is the greatest gift. Nast’s Santa makes his last appearance in Harper’s Weekly the next year when the jolly old (man-size) elf offers himself as a present. Nast’s last two Christmas illustrations in Harper’s Weekly appeared in December 1886, when he resigned from the newspaper, but his impact on the popular image of Santa Claus continued and remains potent to this day. (source: New York Times)

Thomas Nast exhibit from Will Hughes on Vimeo.

No comments:

Post a Comment