African Americans in the Civil War: Equality Earned With Blood

"Freedom to the slave should now be proclaimed from the Capitol, and should be seen above the smoke and fire of every battle field, waving from every loyal flag."

—Frederick Douglass, 1861

From the National Geographic Magazine, "African Americans in the Civil War: Equality Earned With Blood," by Shelley Sperry -- America's Civil War battlefields are sacred in large measure because on that soil a war to preserve the Union became a war to end human slavery. But through the course of the conflict, a new cause emerged, one that anticipated the next century's great struggle as African-American soldiers who fought on those bloody fields demanded not only freedom but equality. In December 1861, less than a year after the guns began firing, Secretary of War Simon Cameron suggested that slaves should be freed and recruited as laborers and soldiers for the Union cause. President Abraham Lincoln responded with a new job for the secretary, who was soon on his way to St. Petersburg as the minister to Russia. A few months earlier two Union generals had attempted to free slaves in areas under Federal control, but superiors nullified their orders. Despite these rebukes, African Americans and their white allies kept emancipation and the right of all Americans to serve in the military at the forefront of public debate about the war.

By July 1862, Lincoln announced to his Cabinet that he would soon be using his war powers to free slaves in the rebellious states. In the same month the Militia Act allowed the Army and Navy to employ "persons of African descent," and, in some cases, granted freedom to the families of those who served. Although designed mainly to let escaped slaves become laborers for Yankee forces occupying the South, the act produced black Army units in New Orleans and the Sea Islands of South Carolina.

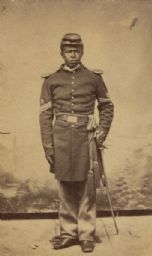

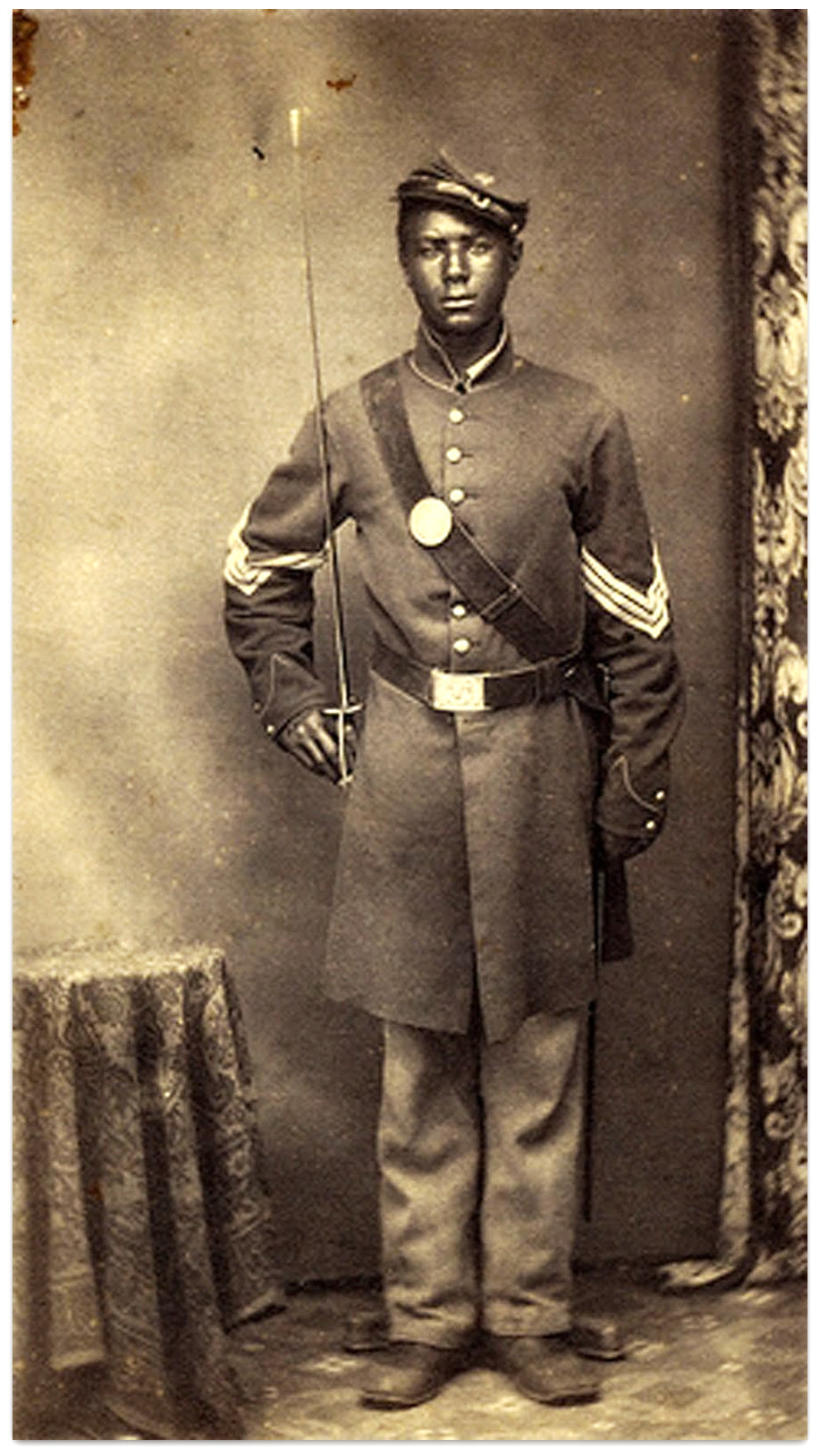

Once Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863—formally allowing the Union Army to recruit African Americans—a wave of volunteers flooded the North. A few months later a new Bureau of Colored Troops began overseeing the segregated units. In key battles at Port Hudson, Louisiana, and Fort Wagner, South Carolina, black soldiers stunned once skeptical white officers with their courage and fighting skills.

But beyond the blood and smoke of the battlefields, African-American soldiers were also engaged in a dramatic fight for equality with their white comrades on two fronts: They wanted to be treated as equals by the enemy as well as by their own government.

"Never let them sell our colored soldiers for slaves"

As soon as African Americans appeared in uniform, the Confederate government declared that captured black soldiers would not be considered prisoners of war but would be treated as fugitive slaves, even if the men had been free upon entering the Army. Many Northerners feared this would mean torture or even murder. Indeed, some Southern officers immediately executed captured black soldiers. A July 1863 letter from Hannah Johnson, mother of an African-American soldier who fought with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry at Fort Wagner, urged the President to act fairly and protect men like her son:

Excellent Sir

. . . I know that a colored man ought to run no greater risques than a white . . . So why should not our enemies be compelled to treat him the same. . . . they said Mr. Lincoln will never let them sell our colored soldiers for slaves, if they do he will get them back quck he will rettallyate and stop it. Now Mr. Lincoln don't you think you oght to stop this thing and make them do the same by the colored men.

Shortly before he received the letter, Lincoln pledged that the Union Army would indeed retaliate against Confederates if the South did not accord black prisoners the same treatment as whites. Yet the North offered no retaliation for Rebel atrocities at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, where scores of black soldiers were massacred in April 1864.

"We have done a Soldiers Duty. Why cant we have a Soldiers pay?"

While the controversy over prisoners of war raged, the U.S. government was using the Militia Act of 1862 to justify paying all black soldiers—whom it regarded as laborers—less than half the monthly wages of white soldiers. African Americans earned ten dollars a month, from which three dollars was deducted for clothing. White soldiers of the same rank received $13 a month plus clothing or cash worth more than three dollars. The Militia Act primarily applied to former slaves who worked as laborers for the Union Army, and many free blacks who had enlisted to serve their country deeply resented treatment that equated them with slaves. In September 1863, Cpl. James Henry Gooding wrote to President Lincoln to state the case of his comrades as clearly as possible:

Now the main question is. Are we Soldiers, or are we LABOURERS. We are fully armed, and equipped, have done all the various Duties, pertaining to a Soldiers life, have conducted ourselves, to the complete satisfaction of General Officers, who, were if any, prejudiced against us, but who now accord us al the encouragement, and honour due us. . . . have dyed the ground with blood, in defense of the Union, and Democracy. . . . We have done a Soldiers Duty. Why cant we have a Soldiers pay?

The men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry continued to serve, but refused to accept any pay at all until the U.S. government—the institution they were fighting to preserve—treated them as equal to their white comrades. What could be more absurd than accepting demeaning wages and treatment based on their race, while sacrificing their lives to end race-based slavery? In response, the governor of Massachusetts convinced the state legislature to make up the difference between the black and white soldiers' pay, but the soldiers refused it. It was a matter of pride. As one declared: "We did not come to fight for money . . . [but for the principle] that made us men when we enlisted."

In November 1863 Sgt. William Walker of the 3rd South Carolina Volunteers led a group of men to lay down their arms in Jacksonville, Florida, and resign from the Army in protest, arguing that they had been promised equal treatment when they enlisted. Walker's case prompted increased public discussion of the issue, and in December Secretary of War Edwin Stanton asked that the pay of all soldiers be equalized. The families of black soldiers suffered as opposition and long debates in Congress delayed the action. In February 1864 Sergeant Walker was court-martialed and shot for mutiny.

Finally, in June 1864 Congress passed legislation giving black soldiers equal pay, retroactive to January 1, 1864, for all soldiers and to the time of enlistment for those who had been free men when they joined. The question of just how the military would determine who was and wasn't a free man upon enlistment was solved creatively by officers who wanted to provide fair compensation for as many as possible. They accepted each man's personal oath about whether he had been free or not and encouraged a "Quaker oath," in which soldiers could declare that by God's law (even if not by human law) they had been free men. By December 1865 the 13th Amendment had abolished slavery throughout the United States.

[http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0504/feature5/online_extra.html]

[http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0504/feature5/online_extra.html]

No comments:

Post a Comment