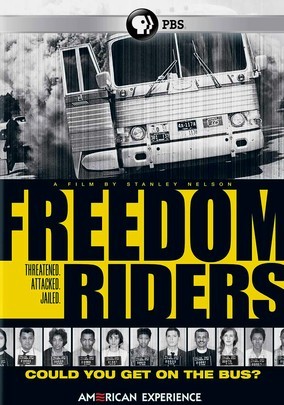

From the New York Times Television Review, "Voices From the Buses on the Road to Civil Rights," by Ginia Bellafante, on 15 May 2011 -- The filmmaker Stanley Nelson has a stunning accomplishment in “Freedom Riders,” a documentary that chronicles a crucial, devastating episode of the civil rights movement, an episode whose gruesome visuals impinged on the perception of American liberty around the world. Commemorating the 50th anniversary of the freedom rides, the film (to be shown Monday on PBS) is a story of ennobled youth and noxious hatred, of decided courage and inexplicable brutality. In May 1961 the Congress of Racial Equality sought to challenge the segregation of interstate travel on public transport and sent forth activists, both black and white, and many of them students, on a bus journey through the South, where they were received with violence that law enforcers refused to tame.

It is hard to imagine a feature film conveying the events with a more vivid sense of drama or suspense. The commentators — the riders themselves, historians, politicians, civil rights leaders — have mostly been chosen for an uncanny ability to convey the tension in a present-tense reconstruction. Blowhards and professors of the obvious have been excised, and the archival photographs and news clips have been edited down to those most affecting and lyrical.

The story told begins like this: On Mother’s Day in 1961 two buses departed Atlanta headed for Birmingham, Ala. CORE leaders assumed that the activists would confront hostility, but they had no idea what would follow. The first bus was burned in Anniston, Ala. Occupants of the second forged on with no knowledge of what their compatriots had just encountered. The riders possessed a fearlessness that leads you to imagine that even if cellphone technology had existed and had allowed them to be warned, little about their plans would have changed.

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson

Birmingham, at the time among the most racially divided cities in the country, was not poised to greet the riders neutrally. The city was ruled by the notorious Bull Connor, a police commissioner economically described here by Julian Bond, a founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, as “some kind of psychopath, rabid on the subject of race.” Connor had allotted the hordes of Klansmen intent on disrupting the arrival of the buses 15 minutes to beat, maim and burn the passengers, with the promise that none would be arrested.

One of the most bizarrely compelling figures to emerge in the film is John Patterson, then Alabama’s governor, who had to be strong-armed by the federal government into offering protection to the riders. He speaks to the cameras now with an oddly casual air and no obvious sense of contrition. He says that he was afraid of Connor. He was also a political opportunist who had won the Democratic gubernatorial primary in 1958 with the support of the Ku Klux Klan. His opponent, George Wallace, had lost with the support of the N.A.A.C.P. (Wallace’s segregationist politics flourished as a result of this defeat.)

“Freedom Riders” implicitly and ably conveys the powerlessness of positive law in the face of a toxic cultural emotionalism. By the time the freedom riders had begun their efforts, the Supreme Court had twice handed down decisions — first in 1946, in Morgan v. Virginia, and 14 years later in Boynton v. Virginia — declaring segregation on buses and trains traveling between states a violation of interstate commerce laws. But Jim Crow traditions meant an ugly disregard for what was already mandated.

By the fall of 1961, 400 Americans had participated in the freedom rides, facing attack and arrest. That September the Interstate Commerce Commission delivered its order to end segregation on buses and in railway stations, and the civil rights movement had an enormous triumph. Now so too does this genre of documentary film. It is easy to imagine “Freedom Riders,” attaining the status of “Eyes on the Prize,” the multipart film on the history of the civil rights movement that has been an essential component of American history classes for years. “Freedom Riders” should have an equally long life.

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: Freedom Riders

Written and directed by Stanley Nelson; based in part on the book “Freedom Riders” by Raymond Arsenault; Mr. Nelson and Laurens Grant, producers; Lewis Erskine and Aljernon Tunsil, editors; Lewanne Jones, archival producer; Stacey Holman, associate producer; Robert Shepard, director of photography; Tom Phillips, composer; Rena Kosersky, music supervisor. For American Experience: Sharon Grimberg, senior producer; Mark Samels, executive producer. (source: New York Times Television Review)

American Experience Freedom Riders

Watch Freedom Riders on PBS. See more from American Experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment