By the 1940s, organized baseball had been racially segregated for many years. The black press and some of their white colleagues had long campaigned for the integration of baseball. Wendell Smith of The Pittsburgh Courier was especially vocal. World War II experiences prompted more people to question segregation practices.

Although several people in major league baseball tried to end segregation in the sport, no one succeeded until Brooklyn Dodger's general manager Branch Rickey set his "great experiment" (See Jules Tygiel's Baseball's Great Experiment in the bibliography) into motion. In 1945, the Jim Crow policies of baseball changed forever when Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson of the Negro League's Kansas City Monarchs agreed to a contract that would bring Robinson into the major leagues in 1947.

In addition to racial intolerance, economic and other complex factors contributed to segregation in baseball. For example, many owners of major league teams rented their stadiums to Negro League teams when their own teams were on the road. Team owners knew that if baseball were integrated, the Negro Leagues would probably not survive losing their best players to the majors, major league owners would lose significant rental revenue, and many Negro League players would lose their livelihoods. Some owners also thought that a white audience would be reluctant to attend games with black players. Others saw the addition of black players as a way to attract larger white as well as black audiences and sell more tickets. Looking back on this time, Rickey described the problems he faced and the events that influenced his decision in a speech to the One Hundred Percent Wrong Club in 1956.

Branch Rickey (1881-1965) was involved with baseball in a variety of capacities -- as a player, coach, manager, and owner -- for more than sixty years. His Hall of Fame plaque mentions both his creation of baseball's farm system in the 1920s and his signing of Jackie Robinson. Rickey's interest in integrating baseball began early in his career. He had been particularly troubled by the policy of barring African Americans from grandstand seating in St. Louis, when he worked for the Cardinals.

The noted sportswriter Red Smith fondly summed up Rickey's multi-faceted persona: "player, manager, executive, lawyer, preacher, horse-trader, spellbinder, innovator, husband and father and grandfather, farmer, logician, obscurantist, reformer, financier, sociologist, crusader, sharper, father confessor, checker shark, friend and fighter." (Editorial page, St. Louis Post- Dispatch, Monday, October 31, 1955)

In 1942, Rickey joined the Dodgers and quietly began plans to bring black players to the team. The first black baseball player to cross the "color line" would be subjected to intense public scrutiny, and Rickey knew that the player would have to be more than a talented athlete to succeed. He would also have to be a strong person who could agree to avoid open confrontation when subjected to hostility and insults, at least for a few years. In 1945, when Rickey approached Jackie Robinson, baseball was being proposed as one of the first areas of American society to integrate. Not until 1948 did a presidential order desegregate the armed forces; the Supreme Court forbid segregated public schools in 1954.

The player who would break the color line, Jack (John) Roosevelt Robinson, was born in Cairo, Georgia, on January 31, 1919. His mother moved the family to Pasadena, California, in 1920, and Robinson attended John Muir Technical High School and Pasadena Community College before transferring to the University of California, Los Angeles. An outstanding athlete, he lettered in four sports at UCLA -- baseball, football, basketball, and track -- and excelled in others, such as swimming and tennis. Consequently, he had experience playing integrated sports.

Robinson showed an early interest in civil rights in the Army. He was drafted in 1942 and served on bases in Kansas and Texas. With help from boxer Joe Louis, he succeeded in opening an Officer Candidate School to black soldiers. Soon after, Robinson became a second lieutenant. At Fort Hood, Texas, Robinson faced a court martial for refusing to obey an order to move to the back of a bus. The order was a violation of Army regulations, and he was exonerated. Shortly after leaving the Army in 1944, Robinson joined the Kansas City Monarchs, a leading team in the Negro Leagues.

After scouting many players from the Negro Leagues, Branch Rickey met with Jackie Robinson at the Brooklyn Dodgers office in August, 1945. Clyde Sukeforth, the Dodgers scout, had told Robinson that Rickey was scouting for players because he was starting his own black team to be called the Brown Dodgers. At the meeting, Rickey revealed that he wanted Robinson to play for the major league Dodgers. Rickey then acted out scenes Robinson might face to see how Robinson would respond. Robinson kept his composure and agreed to a contract with Brooklyn's Triple-A minor league farm club, the Montreal Royals.

On October 23, 1945, Jackie Robinson officially signed the contract. Rickey soon put other black players under contract, but the spotlight stayed on Robinson. Rickey publicized Robinson's signing nationally through Look magazine, and in the black press through his connections to Wendell Smith at the Pittsburgh Courier. In response to allegations that Negro League contracts had been broken, Rickey sought assurances that Robinson had not been under formal contract with the Monarchs. Robinson responded to Rickey in a letter preserved in the Branch Rickey Papers.

After a successful season with the minor league Montreal Royals in 1946, Robinson officially broke the major league color line when he put on a Dodgers uniform, number 42, in April 1947.

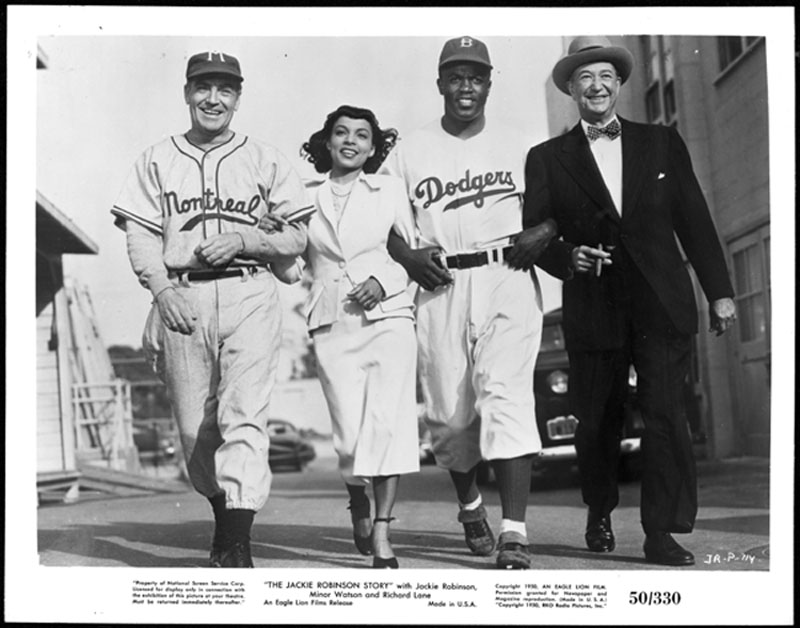

"The Jackie Robinson Story"

No comments:

Post a Comment