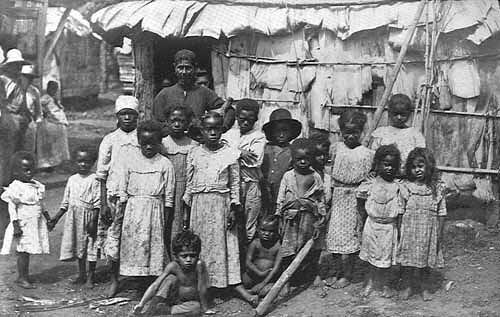

This site is for educational purposes. Slavery in the new world from Africa to the Americas.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Friday, December 30, 2011

Futurama: Hermes' Kwanzaa Party

Watch This Clip: Hermes' Kwanzaa Party

Guests arrive for the Conrad family party, and Kwanzaabot (Coolio) tells everyone how he celebrates Kwanzaa.

Futurama

African American Watch Night

San Francisco Gate, "African American Watch Night Rings In New Year," 29 December 2008, by Wanda Ravernell: There are no party favors, no paper whistles, no shiny hats for these New Year's celebrants. They won't be greeting the new year with a Champagne toast while the ball drops in Times Square.

It will be joyful, but sober, especially during those last 10 minutes when the preacher stops preaching, the choir quiets down and those who are so inclined, get down on their knees and pray.

It's called the Watch Night service, a Methodist custom that African Americans adopted and adapted as a spiritual and political ritual during the time of slavery. It continues today around the nation and the Bay Area, with many remembering the most important Watch Night service, that of Dec. 31, 1862.

Skeptical that President Abraham Lincoln would keep his word about emancipation, African Americans, both free and slave, as well as abolitionists, prayed through the night and into the day. Abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass stayed at a church in Rochester, N.Y., until 10 p.m. on New Year's Day, awaiting a cable that assured him that the law had been passed.

"Our ancestors always believed that they would someday be free," said Lawrence VanHook, Laney College adjunct professor of ethnic studies and pastor of Community Christian Church, "We believed in our prayer, our watching in anticipation of what God would do."

To borrow shamelessly from Dickens, this time of year was the best of times and the worst of times for slaves. Christmas was the best of times because it afforded good eating, less work and permission to visit distant relatives and friends. New Year's Day, also known as "Heartbreak Day," was the worst of times because slave families anticipated being split up as owners would balance their books by auctioning off slaves, as well as hogs and horses.

The institution of slavery first showed signs of cracking with the U.S. ban on slave importation as of 1808. The Civil War brought an official end to the practice with Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of Sept. 22, 1862, to be effective as of Jan. 1, 1863.

In 1862, "there was a lot of politicking and resistance," to Lincoln's plan to free the slaves, said the Rev. Amos Brown of San Francisco's Third Baptist Church. "The slaves decided they would gather and watch through the night for the expectation of the dawn of a new day."

The Jan. 1 Emancipation celebrations began to die out in the North and far West at the beginning of the 20th century, but the custom of Watch Night persists

For some people, it's the only way to bring in the new year. "That's been my party for 61 years," says Pastor Ron Thomas, 61, of the Prayer Tower Church in Oakland. "We're praying out the old year, praying in the new."

"Watch Night, like all worship, is sacrifice," says Third Baptist Church administrator Sharon Haynes. "The significance is just thanking God for getting us through."

But in those perilous times that gave birth to Watch Night, gathering for prayer was also accompanied by a need to know how to navigate the changes. For each new law passed - from the abolition of the slave trade, to the fugitive slave laws and, finally, Emancipation, the year's start was when they determined a response to the news.

This year, the greatest good news to befall the African American community since the end of slavery came early: the election of Barack Obama as president of the United States.

"To make a parallel, (election night) was a lot like Watch Night," VanHook said. "We watched and we waited. We weren't sure he would win. So we watched to be sure."

And watching is not enough. "On the heels of Obama's election," VanHook said, "How do we respond? That's our assignment."

Taking his cue from the old Emancipation Day celebrations, VanHook is sponsoring "Witness to a New Day" a New Year's Day forum featuring Rep. Barbara Lee, to speak to the issues of the nation, and Alameda County Supervisor Keith Carson, to the state of the community.

Brown, who is planning a traditional Watch Night service, is cautiously optimistic about the significance of the election of an African American president.

The gap between dream and reality for African Americans since 1863 is still here, he says. "The masses of black people have not met the fulfillment of dreams prayed for on that Watch Night," he said, referring to Dec. 31, 1862. "Mr. Obama's presidency can go no higher in our agenda than the nation permits him to go."

Although Pastor Dion Evans of Chosen Vessels Christian Church in Alameda will use what he calls a combination of new-school and old-school prayer style when it comes to his own service, he is saddened that so few people are aware of the "Emancipation piece." Knowledge of "history is important for any people to succeed," he said. "(Watch Night) ties New Year into our accomplishments in the history of this country." (source: San Francisco Gate)

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Excerpt from James Baldwin's "The Fire Next Time"

Excerpt from James Baldwin's "The Fire Next Time"

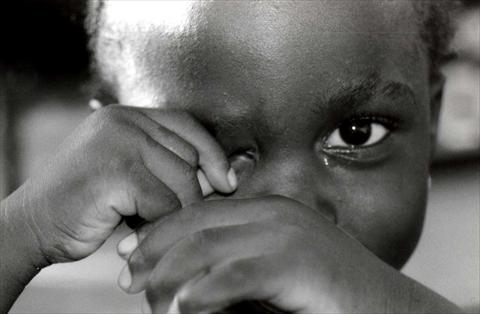

My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation:

Dear James:

I have begun this letter five times and torn it up five times. I keep seeing your face, which is also the face of your father and my brother. Like him, you are tough, dark, vulnerable, moody — with a very definite tendency to sound truculent because you want no one to think you are soft. You may be like your grandfather in this, I don't know, but certainly both you and your father resemble him very much physically. Well, he is dead, he never saw you, and he had a terrible life; he was defeated long before he died because, at the bottom of his heart, he really believed what white people said about him. This is one of the reasons that he became so holy. I am sure that your father has told you something about all that. Neither you nor your father exhibit any tendency towards holiness: you really are of another era, part of what happened when the Negro left the land and came into what the late E. Franklin Frazier called "the cities of destruction." You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger. I tell you this because I love you, and please don't you ever forget it.

I have known both of you all your lives, have carried your Daddy in my arms and on my shoulders, kissed and spanked him and watched him learn to walk. I don't know if you've known anybody from that far back; if you've loved anybody that long, first as an infant, then as a child, then as a man, you gain a strange perspective on time and human pain and effort. Other people cannot see what I see whenever I look into your father's face, for behind your father's face as it is today are all those other faces which were his. Let him laugh and I see a cellar your father does not remember and a house he does not remember and I hear in his present laughter his laughter as a child. Let him curse and I remember him falling down the cellar steps, and howling, and I remember, with pain, his tears, which my hand or your grandmother's so easily wiped away. But no one's hand can wipe away those tears he sheds invisibly today, which one hears in his laughter and in his speech and in his songs. I know what the world has done to my brother and how narrowly he has survived it. And I know, which is much worse, and this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it. One can be, indeed one must strive to become, tough and philosophical concerning destruction and death, for this is what most of mankind has been best at since we have heard of man. (But remember: most of mankind is not all of mankind.) But it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.

Now, my dear namesake, these innocent and well-meaning people, your countrymen, have caused you to be born under conditions not very far removed from those described for us by Charles Dickens in the London of more than a hundred years ago. (I hear the chorus of the innocents screaming, "No! This is not true! How bitter you are!" — but I am writing this letter to you, to try to tell you something about how to handle them, for most of them do not yet really know that you exist. I know the conditions under which you were born, for I was there. Your countrymen were not there, and haven't made it yet. Your grandmother was also there, and no one has ever accused her of being bitter. I suggest that the innocents check with her. She isn't hard to find. Your countrymen don't know that she exists, either, though she has been working for them all their lives.)

James Baldwin: "God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!"

Well, you were born, here you came, something like fifteen years ago; and though your father and mother and grandmother, looking about the streets through which they were carrying you, staring at the walls into which they brought you, had every reason to be heavyhearted, yet they were not. For here you were, Big James, named for me — you were a big baby, I was not — here you were: to be loved. To be loved, baby, hard, at once, and forever, to strengthen you against the loveless world. Remember that: I know how black it looks today, for you. It looked bad that day, too, yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other none of us would have survived. And now you must survive because we love you, and for the sake of your children and your children's children.

This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. Let me spell out precisely what I mean by that, for the heart of the matter is here, and the root of my dispute with my country. You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity. Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth, you have been told where you could go and what you could do (and how you could do it) and where you could live and whom you could marry.

I know your countrymen do not agree with me about this, and I hear them saying, "You exaggerate." They do not know Harlem, and I do. So do you. Take no one's word for anything, including mine-but trust your experience. Know whence you came. If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go. The details and symbols of your life have been deliberately constructed to make you believe what white people say about you. Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity and fear. Please try to be clear, dear James, through the storm which rages about your youthful head today, about the reality which lies behind the words acceptance and integration. There is no reason for you to try to become like white people and there is no basis whatever for their impertinent assumption that they must accept you. The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men. Many of them, indeed, know better, but, as you will discover, people find it very difficult to act on what they know. To act is to be committed, and to be committed is to be in danger. In this case, the danger, in the minds of most white Americans, is the loss of their identity. Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one's sense of one's own reality. Well, the black man has functioned in the white man's world as a fixed star, as an immovable pillar: and as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.

You, don't be afraid. I said that it was intended that you should perish in the ghetto, perish by never being allowed to go behind the white man's definitions, by never being allowed to spell your proper name. You have, and many of us have, defeated this intention; and, by a terrible law, a terrible paradox, those innocents who believed that your imprisonment made them safe are losing their grasp of reality. But these men are your brothers-your lost, younger brothers. And if the word integration means anything, this is what it means: that we, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it. For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become. It will be hard, James, but you come from sturdy, peasant stock, men who picked cotton and dammed rivers and built railroads, and, in the teeth of the most terrifying odds, achieved an unassailable and monumental dignity. You come from a long line of great poets, some of the greatest poets since Homer. One of them said, The very time I thought I was lost, My dungeon shook and my chains fell off.

You know, and I know, that the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon. We cannot be free until they are free. God bless you, James, and Godspeed.

Your uncle,

James [Baldwin]

DukeReads: "The Fire Next Time" by James Baldwin

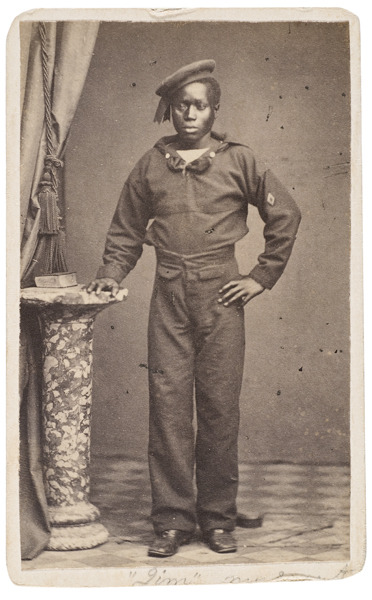

African Americans in the Civil War Navy

Given the wealth of available information about Civil War soldiers, the comparative poverty of such knowledge about Civil War sailors borders on the astonishing. Two explanations account for this imbalance. First, the broad narrative of presidential leadership and the clash of armies in Virginia that Ken Burns's The Civil War told so powerfully all but excludes naval forces from the tale. Second, existing accounts of the naval Civil War have focused on the strategic role of naval forces in the contest, the governmental architects of naval policy, the naval officers who masterminded operations, and the innovations in technology and weaponry to the near exclusion of the enlisted sailors' war. No image of "Jack Tar" comparable to Bell I. Wiley's classic portraits of "Billy Yank" and "Johnny Reb" fills the popular imagination or the works of Civil War historians.1

Because the navy, unlike the army, was racially integrated, understanding the history of black sailors requires some effort but even more interpretive caution to unravel it from that of all Civil War sailors. Exploring the similarities and differences in the experiences of black and white enlisted men must avoid viewing the racial groups in strictly monolithic terms that do not allow for internal complexity and diversity and shifting, if not altogether porous, borders. The work must also beware currently popular understandings of the black soldiers' experience. Often framed around the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, that tale depicts stoic sacrifice and daunting perseverance in pursuit of freedom and equality that in the end was crowned with "Glory," the impression conveyed by the popular feature film. The black sailors' story fits awkwardly, if at all, within that image.

The study of African Americans in the Civil War navy must begin with determining their numbers. During the first decade of the twentieth century, when the secretary of the navy was quizzed about the service of black men in the Civil War, senior officers who had served in the conflict recalled that approximately one-quarter of the enlisted force was black. In a grand display of false precision, the secretary's office concluded that 29,511 black men had served by taking the known figure of Civil War enlistments (118,044) and dividing by four.2 That figure remained essentially unchallenged until 1973, when David L. Valuska's dissertation revised it downward to slightly less than ten thousand men, based upon his survey of surviving enlistment records.3 Over the past decade, a research partnership among Howard University, the Department of the Navy, and the National Park Service has made possible an examination of a fuller array of records than earlier researchers, working as individuals, were able to explore.4 As a result, nearly eighteen thousand men of African descent (and eleven women) who served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War have been identified by name.5 At 20 percent of the navy's total enlisted force, black sailors constituted a significant segment of naval manpower and nearly double the proportion of black soldiers who served in the U.S. Army during the Civil War.6

At the start of the conflict, the army and the navy drew upon separate traditions regarding the service of persons of African descent. Following adoption of the federal Militia Act in 1792, the army excluded black men, and the prohibition remained in effect until the second summer of the Civil War. The navy, in contrast, never barred black men from serving, although from the 1840s onward regulations limited their numbers to 5 percent of the enlisted force. When the war began, several hundred black men were in the naval service, a small fraction of those with prewar experience and a figure well below the prescribed maximum. During the first ninety days after Fort Sumter, when nearly three hundred black recruits enlisted, fifty-nine (20 percent) were veterans with an average of five years of prior naval service per man.7 Over succeeding months, the proportion of black men in the service increased rapidly. At the end of 1861, they made up roughly 6 percent of the crews of vessels. By the summer of 1862, the figure had climbed to nearly 15 percent.8

Civil War U.S. Navy Recruiting Poster; Poster published on behalf of the Naval Rendezvous, Roanoke Island, North Carolina, 8 December 1863. (Photograph from the Naval Records Collection in the U.S. National Archives.)

At first, navy officials did not treat black manpower separately from their general need for men as the service expanded and as volunteer army units competed for the able-bodied. With enlistment centers at the major Atlantic ports from Chesapeake Bay through New England, recruiters could draw upon the international seafaring fraternity to supplement the recruits from the seaboard states. By the end of the war, some 7,700 of the roughly 17,000 men whose place of nativity is recorded had been born in states that remained within the Union. Not surprisingly, the coastal states contributed the largest numbers of men: New York and Pennsylvania roughly 1,200 each, and Massachusetts and New Jersey more than 400 each. Many of these men had been mariners before the war, and still others had worked on the docks and shipping-related businesses of the seaport cities. Additional recruits with prior maritime experience on the lakes and rivers of the nation's interior also enlisted; these included 420 natives of Kentucky. The largest number of black men from any of the northern states— more than 2,300 in all— hailed from Maryland. The maritime culture of Chesapeake Bay, with its numerous tributaries and the port of Baltimore, offer part of the explanation for the large number of Marylanders in naval service. The size of the Maryland contingent also benefited from a spring 1864 agreement between army and navy officials to transfer nearly eight hundred black Marylanders from incomplete units of the U.S. Colored Troops into the navy.9

USS Miami (1862-1865)Members of the ship's crew on the forecastle, circa 1864-65. Frank W. Hackett, a former officer of the ship, wrote in 1910: "The officer standing in the background, at the extreme prow of the ship, is W.N. Wells, Executive Officer. The man in the fore ground with his arm on the nine-inch gun is White, the gunner. Sergeant of Marines, Stanley, is sitting in the fore-ground, near the capstan". Men are playing checkers by the capstan. Anti-boarding nettings are rigged on each side of the ship but rolled up in way of the bow guns. There are a number of black sailors visible among the crew.

Another fifteen hundred men were born outside of the United States, chiefly Canada and the islands of the Caribbean.10 Like their counterparts from the United States, the foreign-born men entered service for a variety of reasons. John Robert Bond, for instance, a mariner of mixed African and Irish descent from Liverpool, England, enlisted during 1863 "to help free the slaves," as his descendants recall. Seriously wounded the following year, he was discharged and pensioned after a long recuperation. He settled in Hyde Park, Massachusetts, amid other black Civil War veterans.11

The remainder of the 17,000 men whose place of nativity is recorded— some 7,800 in all— were born in the seceded Confederate states. The firsthand experience that these men had with slavery distinguished them from their freeborn northern counterparts. Moreover, whereas northern freemen could enlist when they chose, men held in bondage often had to rely on the circumstances of war for the opportunity to do so. Not simply awaiting their fate, black men escaping from slavery helped create opportunities for the federal government to protect them and accept their offers of service. By September 1861, the volume of requests from commanders of naval vessels regarding authorization to enlist fugitive slaves reached such proportions that Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, a Connecticut native of antislavery bent, felt obliged to act. Welles permitted the enlistment of former slaves whose "services can be useful," stipulating that the "contrabands" be classified as "Boys," the lowest rung on the rating and pay scales and one traditionally reserved for young men under the age of eighteen.12 (The term "contraband" itself had within weeks of Fort Sumter sprung into widespread use throughout the North as a rationale for treating such persons as plunder under international conventions of warfare.)

The practical effect of this policy became evident when Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont established federal control of the harbor at Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861. This beachhead eventually became the home port of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, with repair and supply facilities that employed nearly a thousand contrabands. At the same time, vessels in all the squadrons began taking fugitive slaves on board, enlisting the men as needed and forwarding others to places of safety.13

The large concentrations of enslaved African Americans on the plantations along the Mississippi River and the strategic importance of the river to both sides assured that Secretary Welles's directive regarding the employment of contrabands would have special relevance to the Mississippi Squadron. In April 1863, as the combined army and navy assault on Vicksburg, Mississippi, took shape, Flag Officer David D. Porter instructed the commanders of vessels to take full advantage of "acclimated" black manpower.14 Under these guidelines, more than two thousand men enlisted on the vessels that plied the Mississippi and its tributaries.15 The refugee camps that sprang up in Union-occupied areas also proved a rich source of recruits. In the camps of coastal North Carolina, for instance, recruiters from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron displayed posters promising good pay and other amenities and urging volunteers to "Come forward and serve your Country."16

The success of these efforts to recruit black men from the Union-occupied regions of the South tipped the demographic balance among black sailors. Largely free men with considerable naval experience at the start of the war, over time the force included growing numbers of recently enslaved men with only limited maritime experience. Not surprisingly, most were from the states where Union naval forces operated: the Carolinas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The largest contingent of southern-born men, however, was the Virginians, more than twenty-eight hundred strong, numbers of whom had been sold before the war from their native state to plantation regions farther south. The fact that nearly six thousand (roughly 35 percent) of the black sailors whose nativity is known came from the Chesapeake Bay region is striking. Even more so is that more than eleven thousand men were born in the slave states as against four thousand born in the free states. Even allowing for the fact that a small fraction of those from the slave states had been born free, nearly three men born into slavery served for every man born free. Hardly predictable from the record of black sailors in the antebellum navy, this demographic division profoundly influenced the black naval experience during the war.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

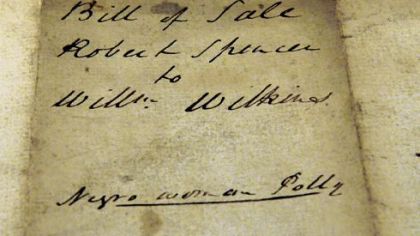

Slave Bill of Sales

1767 Bill of Sale

A handwritten copy of an original bill of sale stemming from 1767. In this transaction, David Hohanas Ackerman of Tapan, NY sold one "Negro boy about three years of age named Less," to Peter Peterse Demary of Hackensack for the sum of twenty pounds. Transcript included From the collections of the Bergen County Historical Society

1770s Bill of Sale

An original bill of sale from the 1770s that details Dirck Terhune's purchase of a "Negro boy named Cyor" from Peter Peterse Demerast of Hackensack for the sum of ninety pounds. Transcript Included From the collections of the Bergen County Historical Society

1782 Bill of Sale

A 1782 slave bill of sale for a man named Tom, a "wench" named Dinah and two children named Sam and Luce. Sold by Elias Romaine of Bergen County to Abraham Ely for 76 pounds, 10 shillings in gold and silver. Transcript Included From the collections of the Bergen County Historical Society

1784 Slave Sale Between Brothers

A 1784 letter from Isaac Van Geson of Secaucus to his brother regarding the sale of a slave named Terance. Transcript Included From the collections of the Bergen County Historical Society

1790 Bill of Sale

A bill of sale from 1790 detailing the account of Richard Reyson of Pompton who purchased a slave named Claus after a four week trial. From the collections of the Bergen County Historical Society

An original bill of sale from 1806 that details John A. Holmes' purchase of a Negro named Abraham from Jacob Lawrence of Township of Middletown, Monmouth County for $275. Transcript Included From the collections of the New Jersey Historical Society

1815 Bill of Sale

A handwritten bill of sale detailing Richard N. Terhune's purchase of a 12 year-old "Negro Boy named Jack," from Benjamin Vreeland of New Barbadoes Township. Transcript included. From the collections of the Bergen County Historical Society

Colonial Will & Inventory - 1747 &1748

A "Colonial Will" from 1747 listing the possessions of Nathaniel Irish of Bethlem, Hunterdon County, NJ. In this will, it is stated that Nathaniel Irish will bequest his daughter "a negro woman named Martilla, and her daughter, Betty. Also included, is a letter inventory of a firm named Allen & Turner, amongst their possessions are a grist mill worth £23; tools worth £12; and 18 negroes worth £600.(source: http://sites.bergen.org/ourstory/Resources/slave&war/sl_primary.htm)

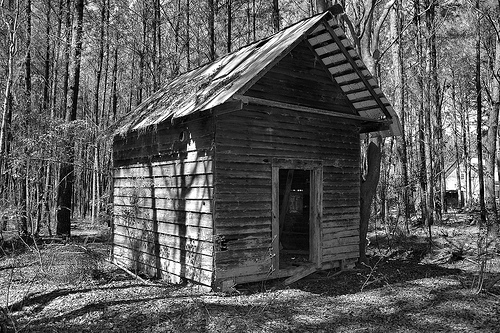

CHAPTER 3: THE SLAVES’ NEW YEAR'S DAY.

CHAPTER 3: THE SLAVES’ NEW YEAR'S DAY.

DR. Flint owned a fine residence in town, several farms, and about fifty slaves, besides hiring a number by the year. Hiring-day at the south takes place on the 1st of January. On the 2d, the slaves are expected to go to their new masters. On a farm, they work until the corn and cotton are laid. They then have two holidays. Some masters give them a good dinner under the trees. This over, they work until Christmas eve.

If no heavy charges are meantime brought against them, they are given four or five holidays, whichever the master or overseer may think proper. Then comes New Year's eve; and they gather together their little alls, or more properly speaking, their little nothings, and wait anxiously for the dawning of day. At the appointed hour the grounds are thronged with men, women, and children, waiting, like criminals, to hear their doom pronounced. The slave is sure to know who is the most humane, or cruel master, within forty miles of him. It is easy to find out, on that day, who clothes and feeds his slaves well; for he is surrounded by a crowd, begging, "Please, massa, hire me this year. I will work very hard, massa." If a slave is unwilling to go with his new master, he is whipped, or locked up in jail, until he consents to go, and promises not to run away during the year. Should he chance to change his mind, thinking it justifiable to violate an extorted promise, woe unto him if he is caught!

The whip is used till the blood flows at his feet; and his stiffened limbs are put in chains, to be dragged in the field for days and days! If he lives until the next year, perhaps the same man will hire him again, without even giving him an opportunity of going to the hiring-ground. After those for hire are disposed of, those for sale are called up. O, you happy free women, contrast your New Year's day with that of the poor bond-woman! With you it is a pleasant season, and the light of the day is blessed. Friendly wishes meet you every where, and gifts are showered upon you. Even hearts that have been estranged from you soften at this season, and lips that have been silent echo back, "I wish you a happy New Year."

Children bring their little offerings, and raise their rosy lips for a caress. They are your own, and no hand but that of death can take them from you. But to the slave mother New Year's day comes laden with peculiar sorrows. She sits on her cold cabin floor, watching the children who may all be torn from her the next morning; and often does she wish that she and they might die before the day dawns. She may be an ignorant creature, degraded by the system that has brutalized her from childhood; but she has a mother's instincts, and is capable of feeling a mother's agonies. On one of these sale days, I saw a mother lead seven children to the auction-block. She knew that some of them would be taken from her; but they took all.

The children were sold to a slave-trader, and their mother was bought by a man in her own town. Before night her children were all far away. She begged the trader to tell her where he intended to take them; this he refused to do. How could he, when he knew he would sell them, one by one, wherever he could command the highest price? I met that mother in the street, and her wild, haggard face lives to-day in my mind. She wrung her hands in anguish, and exclaimed, "Gone! all gone! Why don't God kill me?" I had no words wherewith to comfort her. Instances of this kind are of daily, yea, of hourly occurrence. Slaveholders have a method, peculiar to their institution, of getting rid of old slaves, whose lives have been worn out in their service. I knew an old woman, who for seventy years faithfully served her master. She had become almost helpless, from hard labor and disease. Her owners moved to Alabama, and the old black woman was left to be sold to any body who would give twenty dollars for her.

(source: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/jacobs/hjch3.htm)

Friday, December 23, 2011

‘Cream of Wheat’ Man Finally Gets A Tombstone

From the Seattle Times on 17 June 2007: LESLIE, Mich. — A man widely believed to be the model for the smiling chef on Cream of Wheat boxes finally has a grave marker bearing his name.

Frank L. White died in 1938, and until last week, his grave in Woodlawn Cemetery bore only a tiny concrete marker with no name.

On Wednesday, a granite gravestone was placed at his burial site. It bears his name and an etching taken from the man depicted on the Cream of Wheat box.

Jesse Lasorda, a family researcher from Lansing, discovered that White was born about 1867 in Barbados, came to the United States in 1875 and became a citizen in 1890. When White died Feb. 15, 1938, the Leslie Local-Republican newspaper described him as a "famous chef" who "posed for an advertisement of a well-known breakfast food."

Frank L. White, believed to be the model for the smiling chef, died in 1938

White lived in Leslie for about the last 20 years of his life, and the story of his posing for the Cream of Wheat picture was known in the city of 2,000, located between Jackson and Lansing and about 70 miles west of Detroit.

The chef was photographed about 1900 while working in a Chicago restaurant. His name was not recorded. White was a chef, traveled a lot, was about the right age and told neighbors he was the Cream of Wheat model, the Jackson Citizen Patriot said. (source: Seattle Times )

1897 Christmas Day in a Virginia Town

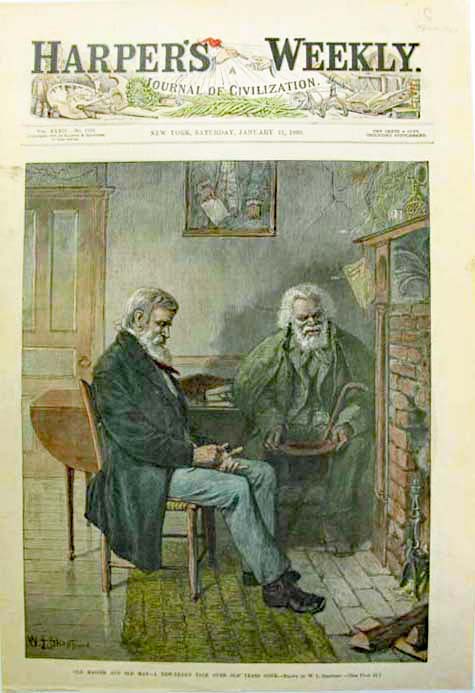

Harper's Weekly "Old Master and Old Man - A New-Year's Talk Over Old Years Gone" January 11, 1890

Harper's Weekly "Old Master and Old Man - A New-Year's Talk Over Old Years Gone" January 11, 1890

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)