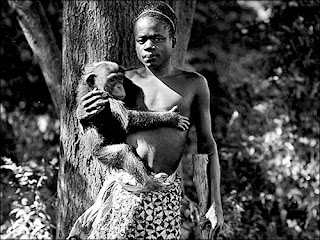

Ota Benga in the Bronx Zoo

From the Washington Post, "Basest Instinct: Case of the Zoo Pygmy Exhibited a Familiar Face of Human Nature," by Ann Hornaday, a Washington Post Staff Writer, on 3 January 2009 -- It's not unusual for a minor, obscure historical figure suddenly to bubble up into the zeitgeist. (Remember the year of two Truman Capote movies?) But the inspiration for what might be the most arcane cultural reference of 2008 turned out to have particular, grievous resonance for me. His name is Ota Benga.

If you saw the wildly imaginative movie "The Fall" in the spring, you might recognize the name. The film, directed by Tarsem Singh, featured a former slave named Otta Benga as one of its larger-than-life fictional heroes. Then, in September, Texas venture capitalist Bill Perkins took out an ad in the New York Times criticizing the financial bailout; the full-page illustration was designed by a Houston-based art collective called Otabenga Jones. Ota Benga has inspired musicians, including the Brooklyn experimental band Piñataland. Someone has set up a MySpace page in his name.

But nowhere has Ota Benga been more obviously referenced than in "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button," in which an African Pygmy befriends the title character, a young man in an old man's body. While the two explore the racier pleasures that New Orleans has to offer, the Pygmy -- in the film he's called Ngunda Oti -- cheerfully tells Benjamin of his various adventures, which happen to include being put in a zoo and exhibited in the monkey house.

It's that scene that set my stomach churning. Because it was Ota Benga who, in 1906, was actually put on display in the Bronx Zoo. And it was my great-great-great-uncle who put him there.

Ota Benga's story began at the turn of the last century, in the forests of the Congo Free State, where he and his fellow tribesmen hunted elephant and antelope for subsistence, fending off hostile tribes and the murderous forces of Belgian King Leopold's Force Publique. In 1904, Benga was brought to the United States by the missionary, explorer and entrepreneur Samuel Phillips Verner, who had been hired by the St. Louis World's Fair to bring back Pygmies for an ethnographic exhibit. (Verner's story was recounted by his grandson Phillips Verner Bradford in the book "Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo," from which much of this account was taken.) Verner purchased Benga, whose wife and children had been killed in a massacre, from African slave traders, most likely saving his life. Later he brought Benga, seven other Pygmies and a young Congolese man to St. Louis, having promised to return the eight Pygmies when the fair ended.

The nine Africans proved to be one of the most popular attractions at the fair, where the crowds gawked, jeered and at one point threw mud pies at the human exhibit. From St. Louis, the group traveled to New Orleans just in time for Mardi Gras, and finally back to Africa, where eventually Benga -- expressing a desire to learn to read -- asked Verner to take him along when the explorer returned home. They arrived in New York in August 1906, when Benga's second and even more bizarre American odyssey began.

For generations, William Temple Hornaday has been the most storied and illustrious member of the Hornaday family tree, which has its roots in 18th-century Quaker settlements of North Carolina. A famous naturalist, he was a contemporary of Theodore Roosevelt's, a zealous ecological evangelist and preserver of wildlife who is credited with saving the American bison, among other species. A mountain peak in Yellowstone and an entire range in Mexico are named after William Temple Hornaday, as well as parks, a street in New York and a special Boy Scout medal for distinguished service in conservation. To most environmentalists, wildlife biologists and lovers of the outdoors, Hornaday is a hero.

My father never met "Temple," as he called his great-great-uncle. But he often related stories passed down from his own father, who recalled him as an eccentric man -- a teetotaler, for example, known to make an exception for a glass or two of champagne. Another favorite family tale was how during his stint as the first director of the New York Zoological Park (more commonly known as the Bronx Zoo), Temple invited my grandfather, then a medical student, to come to New York and oversee the monkey house. (Before running the Bronx Zoo, Temple spent eight years at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, where he helped plan the National Zoo.)

The Bronx Zoo Monkey House, 1910

That would have been the same monkey house where Temple displayed Ota Benga, but I'd never heard his name until several years ago, when I heard his story on the radio. I was sipping coffee and reading the paper, wondering with half an ear how anyone could put a fellow human being in a zoo, when the name "William Temple Hornaday" rang out. I put the coffee down, mortified, and listened more closely. In 1906, Verner, looking for a place for Benga to live, finally brought him to the Bronx Zoo, where Temple welcomed him and, at first, simply let him walk the grounds, helping the workers, befriending the animals and keeping a relatively low profile. But one early September weekend, Temple decided to move Benga's hammock into an orangutan's cage, where he encouraged Benga to engage in such "picturesque" activities as playing with his simian companion, weaving caps out of straw and shooting his bow and arrow.

Outside the enclosure, Temple installed the following sign: "The African Pygmy, 'Ota Benga.' Age, 28 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches. Weight 103 pounds. . . . Exhibited each afternoon during September."

It's tempting to see Temple's behavior as the random, racist act of an unusually insensitive outlier. But the more unsettling truth is that he was probably a typical, if exceptionally blinkered, product of his era. This was a time in which sideshows and arcades featured lurid burlesques on primitive themes and "authentic" Americana, in which the hucksterism and hustle of P.T. Barnum meshed commerce and mass culture, in which Jim Crow was at its height, lynchings were preserved for posterity on postcards, eugenics was gaining popularity and Darwin's theory of evolution was making inroads against encroaching notions of creationism. Putting human beings on display was nothing new: Nearly a hundred years earlier, Saartjie Baartman, from what is now South Africa, was exhibited in Britain as the "Hottentot Venus." Along with Ota Benga, Geronimo was a popular attraction at the St. Louis World's Fair, the Apache warrior and U.S. prisoner of war by then relegated to a booth selling souvenirs and autographs.

Saartjie Baartman

It was most likely in the spirit of both Barnum and Darwin that Temple hit on the disastrous idea of putting Benga in the cage. The display, marketed with the right mix of sensationalism and pseudoscientific pretense, would have the double benefit of bringing in throngs of visitors to the zoo and advancing Darwin's theories, with Benga cast as the missing link. Ironically, it was on both those counts that black church leaders expressed outrage upon hearing of Benga's captivity. "Our race, we think, is depressed enough without exhibiting one of us with the apes," one minister wrote to New York's mayor, George McClellan (son of the Civil War general). Furthermore, he added, "the Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favor should not be permitted."

Reportedly, it didn't take long for Temple to cancel the monkey house exhibit, his otherwise impenetrable shell of hubris, condescension and naivete unequal to the controversy that he had unleashed. Benga stayed at the zoo for several more days before he went to live in a home for African American orphans in Brooklyn, eventually settling in Lynchburg, Va., where he befriended the poet Anne Spencer. He died in 1916, after shooting himself in the heart.

Hornaday retired from the zoo in 1926 and continued to lobby on behalf of the environment as a director of the Permanent Wildlife Protection Fund. He died in 1937 and was buried in Stamford, Conn., with 16 Boy Scouts serving as an honor guard. In "The Hornadays, Root and Branch," a family tree published in 1979, Temple is called "an original, unusual man" and "a major figure among early giants of conservation."

The name Ota Benga is never mentioned.

When I first heard about Ota Benga, I asked my father whether he knew about him. He responded immediately and un-self-consciously. "Oh yes," he said, his voice trailing off, an ellipsis that served as an apt metaphor for America's ongoing conversation about race, in which so much has gone unspoken, misremembered and distorted over hundreds of years. It's the same silence that explains why it's common to meet descendants of slaves, but far more rare to meet descendants of slave owners. It's the same silence that lets so many white Americans think of race as someone else's story.

St. Louis World's Fair, 1904

How are sins of the fathers -- or the great-great-great-uncles -- properly accounted for by their successors? The moment I heard Temple's sordid story on the radio, my first impulse was to gain as much distance as possible. "He's not my relative," I remember thinking for an addled moment. "I'm adopted!" Although it's true I'd been adopted as an infant, issues of blood and biology had never been major preoccupations. But for a brief instant I succumbed to the very genetic determinism that Temple himself might have endorsed.

Upon reflection, of course, I was right and wrong. Temple's descendants, biological or otherwise, obviously bear no direct responsibility for what he did. Our only responsibility, to the degree that we take pride in the family name, is to tell the story it represents fully, even when it doesn't follow a straight line of worthy accomplishment and moral rectitude.

For the past decade or so, I've taken to compulsively telling people about Temple and Ota Benga, especially when I meet someone familiar with the more heroic version of my distant uncle's story. Generally, the conversation begins with someone recognizing an uncommon last name. "Do you happen to be related to . . . ?" they'll ask.

With pleasantries about bison and Boy Scouts exchanged, I'll inevitably feel compelled to complete the record. "Did you know he put a Pygmy in a zoo?" I always blurt out a little too loudly. The full light of history often casts contradictory shadows, where a teetotaler drinks champagne and the better angels of a man's nature bumptiously coexist with his demons. (source: Washington Post)

How to Place Slavery into British Identity - Dr William Pettigrew

ReplyDeleteMmmmhhhh....Africa my mother land.....lest I forget my true origin

ReplyDeleteWe, the Christian, sent missionaries to Africa and Australia to bring Christ and the good news of salvation to the natives whereas the evolutionist brought them back as half humans, putting them in cages and calling them "the missing link".

ReplyDeletebape

ReplyDeletebape outlet

kd12

yeezy

kd 13