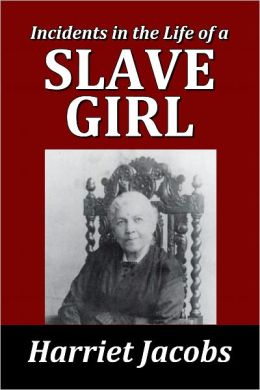

As reported by the Baltimore Sun, "A bitter Inner Harbor legacy: the slave trade: City Diary," by Ralph Clayton on 12 July 2000 -- THOUSANDS of NAACP members descended on Baltimore for their convention this week, prompting visits to the major tourist attractions that line the Pratt Street corridor.

What most of the hundreds of thousands of tourists who visit the Inner Harbor each year don't realize is that they are walking on sacred ground, where countless thousands of men, women, and children suffered during Baltimore's darkest hour.

Between 1815 and 1860, traders in Baltimore made the port one of the leading disembarkation points for ships carrying slaves to New Orleans and other ports in the deep South. Interstate traders in the domestic coast slave trade found Baltimore's excellent harbor, central location and position in the midst of a developing "selling market" attractive incentives in which to build their slave pens and base their operations near the bustling port.

The major slave dealers, who came from Kentucky, Georgia, Virginia and Tennessee built their slave pens near Pratt Street, the major east-west connection to the wharves in the Inner Harbor and Fells Point.

One of the first major pens was built behind a white frame house near the corner of Cove and Pratt streets, near the intersection of what is today Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. The pen belonged to Tennessee native Austin Woolfolk, whose reign in Baltimore ran from 1818 to 1841.

Georgia native Hope Hull Slatter constructed his pen in 1838, several doors east of Howard and Pratt streets. During his 14-year stay, Slatter was ably assisted by his male slave, a jail steward.

By the late 1850s, Joseph Donovan, who had used pens on Pratt Street and Camden Street near Light Street, had a new pen constructed on the southwest corner of Camden and Eutaw streets, near where the Babe Ruth statue now stands at Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

Many other traders made their mark in Baltimore during the height of the slave trade: James Franklin Purvis, whose pen was on Harford Road near Aisquith; Bernard M. and Walter L. Campbell, whose pen was on the south side of Conway Street, near Hanover Street. (He would later buy Slatter's pen after Slatter's departure for Mobile, Ala., in 1848); William Harker, several doors south of Baltimore Street, on the west side of Calvert Street; and John Denning, on Frederick Street, several hundred feet behind the current site of the Holocaust memorial.

The "travelling traders" like George Kephart of Maryland, David Anderson of Kentucky, and Barthalomew Accinelly of Virginia came to town, gathered purchased slaves, and shipped them on packets that regularly made the run from Baltimore to New Orleans.

Although numerous wharves at Fells Point were used by the packet ships, so were the Pratt Street wharves that lined the north side of the Inner Harbor. The site of the current Pratt Street Pavilion, once underwater, was the home to numerous such packets as well as the docks that housed their agents' offices.

The methods for moving the slaves down Pratt Street differed, depending on the trader. Woolfolk preferred to march his slaves in the middle of the night, chained together and on foot. Slatter often used carriages and omnibuses to convey his slaves to the packet ships.

Ships with names like Agent, Architect, Hyperion, General Pinckney, Intelligence, Kirkwood, Tippecanoe and Victorine made their runs from wharves along the Inner Harbor as well as Fells Point.

Greed made for strange bedfellows. Many of Baltimore's slave dealers shipped together on the same brigs, barks, ships and schooners making their cyclical runs to New Orleans. In October 1845, Campbell, Donovan and Slatter shipped 117 souls aboard the Kirkwood from the Frederick Street dock. The Tippecanoe sailed from Chase's wharf in January 1842 with 114 souls shipped by Purvis, Slatter and others.

For 45 years, thousands of families and individuals were sent south on their final passage. For most on board, this meant a death that came when families and loved ones were separated and "sold South" -- a separation from which few returned. It also signified almost certain separation from one another in New Orleans; large families were rarely sold to the same buyer.

![[BaltSlaveTrade.JPG]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgYRj-PsFwpfE-YKFqnLDiLLil8ARVbaD6hHQwcPt_TMlDMe15aX7ud2ECHgdeOv2MqkNnab3FaudChsDuSkCZPCqOhfx8c6b8bRff-Ta1bVncw2WUImJMEzTLr-m8zcFLAz1Y47R1GHxQH/s320/BaltSlaveTrade.JPG)

Tourists who go to the attractions of the harbor area this summer should take time to remember the price that so many paid in blood and broken hearts on Pratt Street.

Remember the young woman who took her and her child's life in Woolfolk's pen in the spring of 1826, rather than go south; the man who, in 1821, upon learning that he had been sold to a trader, slit his own throat at one of Baltimore's wharves; or the unsuccessful attempt in1846 of a female slave to drown herself at the Light Street dock rather than live another day in slavery.

Remember.