Complicity' Explores Hypocrisy Of North's Virtue, book review, on 26 September 2005, by WALTER W. WOODWARD; Special to The Courant Walter W.. Woodward is Connecticut State Historian and an assistant professor of history at the University of Connecticut.

Here is a book you may not want to pick up but won't be able to put down. It is history written with the urgency of breaking news, a journalist's ear for the perfect quotation and an unflinching sensitivity to the human dimensions of a most intentionally inhuman institution.

It addresses an ugly historical reality to which readers of The Courant have already been partially exposed through two special issues of its Northeast magazine. What those publications began, the book completes.

``Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited From Slavery'' is a powerful indictment of the American North for its pervasive racism both before and after the Civil War and for its full complicity in profiting from and practicing enslavement.

``Complicity,'' by Anne Farrow, Joel Lang and Jenifer Frank (Ballantine Books, 288 pp., $25.95), explodes the myth of moral superiority with which Northerners have mantled themselves since the Civil War. In 10 image-rich chapters, the North's profound engagement with slavery from the 1600s to the 1900s -- yes, the 1900s -- is told through stories that will surprise and disturb.

The authors begin with the 1861 declaration by Mayor Fernando Wood that New York City should secede from the United States. His reasoning was simple. Southern cotton -- slave-picked, -ginned and -baled -- was the lifeblood of New York's economy.

The fulcrum of an international cotton trade, New York merchants scrambled to supply Southern planters with luxury goods while the city's shipwrights built vessels to transport cotton and sometimes human merchandise. Wood believed New York's best interests lay in following the money -- right out of the Union.

The slave-based profits made by the South's Lords of the Lash were matched in New England by those of the Lords of the Loom, northern industrialists whose mills in 1850 consumed 150 million pounds of cotton a year. Ironically, America's first power-driven mill was funded by a Providence abolitionist, Moses Brown, whose brother John tried to succeed in the slave trade. Cotton indeed became, as Emerson said, ``The thread that holds the union together,''

New England's economic dependence on slavery did not begin with Eli Whitney's cotton gin. ``Complicity'' looks back to the 17th-century Puritan trade with the West Indies, when Yankee food, horses and wood sustained a Caribbean sugar industry that consumed slaves by the tens of thousands.

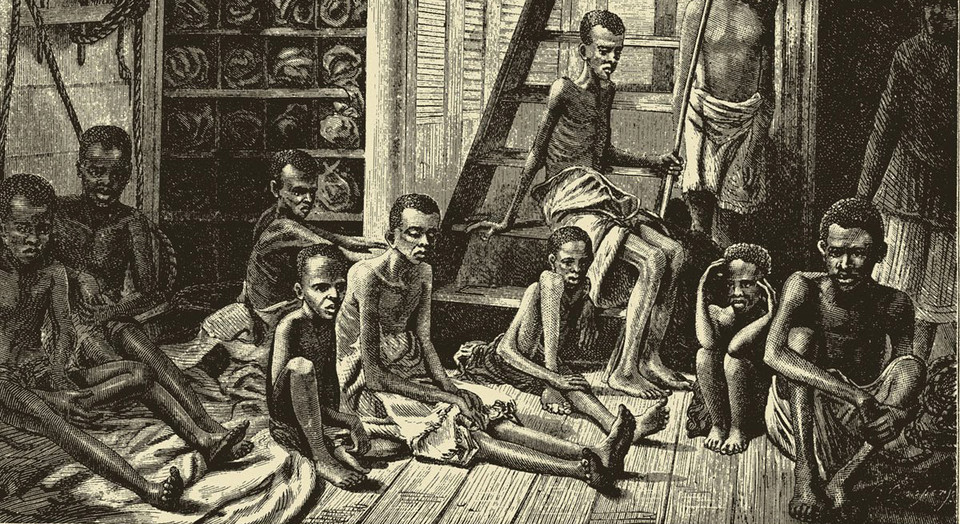

Slave plantations in Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York supported that trade. So did the slave traders of Newport and Bristol, R.I., who in the 18th century carried rum distilled from West Indies molasses to Africa to trade for slaves at 150 gallons per man. Rhode Island slavers transported more human cargo across the Middle Passage than any other American state. Even after slave trading was made a capital crime in 1820, a contraband trade continued out of New York until the Civil War.

The North never had the slave populations the South did. But was Northern captivity -- in which slaves were raised ``family style''-- more benign than its Southern counterparts? Chapters on the life of the Connecticut captive Venture Smith and the 1741 slave uprising in New York that led to 13 slaves' being burned at the stake help convey the cruelty embedded in the Northern slave experience as well as the many forms of resistance employed by captive people.

Northerners still take pride in their participation in the Underground Railroad. Few mention its counterpart, the kidnapping of free blacks from the North into slavery. This practice was rampant, especially in the mid-Atlantic states, where gangs of kidnappers made being free uncertain and insecure. ``Complicity'' documents this as another form of slave trade, sanctioned by racism, fugitive slave laws and onerous Supreme Court decisions. It also documents the Northern hatred that greeted abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Prudence Crandall. Particularly moving are the stories of Elijah Lovejoy, assassinated while defending his printing press from a mob in Alton, Ill., and the brief but powerful recounting of the life and death of John Brown.

Belief in white supremacy lay at the heart of Northern tolerance for slavery and racism. ``Complicity'' documents how 19th-century Northern intellectuals provided a scientific foundation for the most extreme forms of racism. The Philadelphia physician Samuel George Morton's study of skull sizes led him to argue that whites and blacks were permanently different. His colleague Josiah Nott and Harvard's Louis Agassiz went further, saying whites and blacks were different species, blacks permanently inferior.

The most powerful chapter of ``Complicity'' may be the last, which tells of the late-19th-century rise to prominence of the towns of Ivoryton and Deep River. Their wealth came from producing a product essential for that staple of Victorian refinement, the parlor piano. This product, ivory veneer for piano keys, was cut from the heavy elephants' tusks carried by slaves from deep in the African interior to the coast for shipment to Connecticut.

Two businesses, one owned by abolitionists, the other by a utopian industrialist, controlled 75 percent of the ivory production in America. Yet neither had a problem growing rich through a trade that led -- through their purchases alone -- to the deaths or enslavement of 2 million Africans. This ability to separate profit from human rights is a characteristic of so many of the Northern whites who figure in ``Complicity.''

``What kinds of people were these?'' I wonder indignantly. Only later, when I slip on my Malaysia-manufactured shoes and Mexico-manufactured slacks and shirt and sit in my bargain-priced Thailand-manufactured chair, do I realize the truth: They were people like me.

Professional historians may find a number of things to quibble about in ``Complicity.'' It makes a huge argument by selectively surveying moments that emphasize Northern racism and slavery. The authors make no effort to explain why, for instance, New York City did not secede, and why hundreds of thousands of Northerners abandoned the cotton economy to battle the South.

There is, I think, an element of special pleading in this book. But it is an effort to counter-balance a myth about Northern virtue that itself has been based on special pleading of the most tenuous kind.

For that reason, and because of the quality of its writing, the power of its narrative and the clarity of its voice, you should read this book -- and get others to do so, too. (source: Hartford Courant)