The New York Times, "When the Civil War Came to New York, by Jon Grinspan, on 13 July 2013 -- SGT. ROBERT McCREDIE’s men hustled down 43rd Street, turned onto Third Avenue and stopped dead. Looking north, they beheld a sight no Manhattan police officer ever expected to see. A “ragged, coatless, heterogeneously weaponed army,” in the words of one reporter, filled the boulevard two blocks uptown. The smoke of burning factories framed this rumbling multitude.

Sergeant McCredie’s eyes focused on a handful of soldiers sprinting his way, with the mob on their heels. As the troops neared, he could see the tears in their uniforms, the bruises on their faces, the terror in their eyes.

The Civil War had come to New York.

It was the Union Army draft that touched off the four days of rioting on July 13, 1863. Or was it racism? Or immigration? Or politics? It is fitting that the largest riot in American history should have so many causes. Ever since it ended, Americans have struggled to explain why a draft rebellion, a race riot, a class war and an immigrant uprising all erupted in the middle of a civil war fought in the name of unity.

The draft was the immediate cause of the trouble. As the war went badly for the North in the spring of 1863, Union leaders worried that few of the initially optimistic volunteers would re-enlist when their terms were up in 1864. So Congress established America’s first conscription system (the Confederacy already had one).

Enrolling officers entered all men between 20 and 35 years old, and unmarried men up to 45, in a lottery. Those drafted could join the Army, find a substitute or pay $300. Congress hoped this fee would prevent a bidding war for substitutes, but it was far beyond the means of the average American worker.

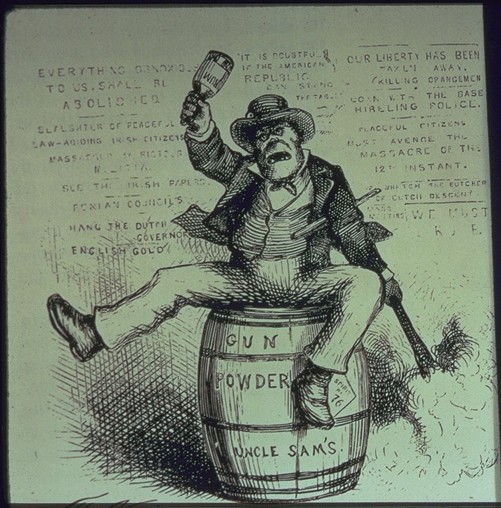

Forcing men into combat represented the greatest demand the federal government had ever put on its citizens, and it did not sit well with New York’s immigrant laborers. They were largely against the war and predominantly Democratic, and they chafed under a Republican-controlled White House, Congress, mayor’s office and, perhaps worst of all, local police force.

White supremacists fanned existing hatred, blaming African-Americans for conscription. Street-corner demagogues shouted: “There would have been no draft but for the war — there would have been no war but for slavery, the slaves were black, ergo, all blacks are responsible for the war.” New York’s black community, centered in Greenwich Village, became a scapegoat for growing anger at Washington.

Working conditions provided the riots’ final cause. New York was rapidly maturing into an industrial behemoth. From Lower Manhattan to Midtown, the island was an unbroken cluster of homes and businesses. Farther north the grid was only partly filled. Here and there factories and tenements popped up, like pimples on the forehead of the adolescent city.

Poorly paid and unprotected laborers built this metropolis. Many were recent immigrants, living in squalid, stinking neighborhoods along the rivers, seething with the belief that while the government fought for emancipation in the South, no one seemed to care about wage slavery in Manhattan.

So it stood on July 13, 1863, the muggy, hushed Monday when the lottery was to begin. Democratic politicians gave ominous warnings that the draft could not be enforced, but no one could predict what the day held.

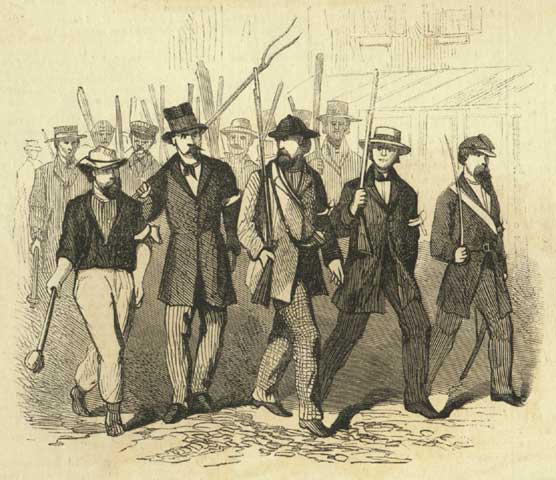

The morning began with a peaceful strike. Organizers moved through uptown factories and construction sites, recruiting protesters. Artisans, firemen and gangs of boys joined as well, waving banners, hollering slogans and swigging whiskey. Women turned out, too, “stalwart young vixens and withered old hags,” wrote one upper-class observer, “swarming everywhere, all cursing the ‘bloody draft’ and egging on their men to mischief.”

Soon two massive columns were streaming down the East and West Sides. When one reached the lottery offices, at 46th Street and Third Avenue, firemen stormed inside, smashed the selection wheel and set the building on fire. Hooligans began to tear up railroad tracks and telegraph lines. Downtown, rumors spread that someone was disabling Manhattan’s infrastructure; many believed it was the beginning of a Confederate plot.

The police superintendent, John Kennedy, pushed his way through this crowd. Around him he heard masses murmuring his name. Soon they were shouting it. Tough old Kennedy felt a shove from behind. When he turned, a man in a tattered Army coat struck him in the face.

That first blow broke the spell of his authority. The throng pushed in, pummeling him. Mr. Kennedy tried to run, but the swaying crush tripped him, dragged him to a muddy hole and forced his head under the dirty water. Mr. Kennedy broke free, and just as the crowd closed in again, a Democratic ward boss pulled him into a carriage and they fled.

Rioters began to surround African-Americans at random. Frenzied gangs attacked black males, some as young as 9 years old. Victims were beaten, stripped, mutilated and dragged through the streets; several were killed, and some were lynched from lampposts. A swarm set upon the Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street, burning it to the ground as 200 children scrambled out a back exit.

Surveying the ruins, one diarist later snarled: “This is a nice town to call itself a centre of civilization!” Other gangs attacked the police. If caught, officers faced the same atrocities as African-American victims. The grotesque beating death of Col. Henry O’Brien lasted six hours. The only authorities who could safely move among the crowds were priests, firemen and Democratic politicians.

The city seemed helpless that first terrible night. Ordinary citizens put out their lamps, fearing a brick through the window. Prominent abolitionists sat in the dark with loaded revolvers, watching for rioters’ torches.

Herman Melville wrote his poem “The House-Top” about looking out over an eerily dark Manhattan, listening to store windows shattering. The riot mocked the very idea of progress, he wrote, as “all civil charms ... like a dream dissolve / And man rebounds whole aeons back in nature.”

New York’s leadership dithered. Elites milled about the well-defended St. Nicholas Hotel, debating the best course. Manhattan’s upper class was split between Democrats who blamed “insolent Negroes” and cautioned moderation toward the troublemakers, and Republicans who called for an “immediate and terrible” response, hoping to see “war made on Irish scum.”

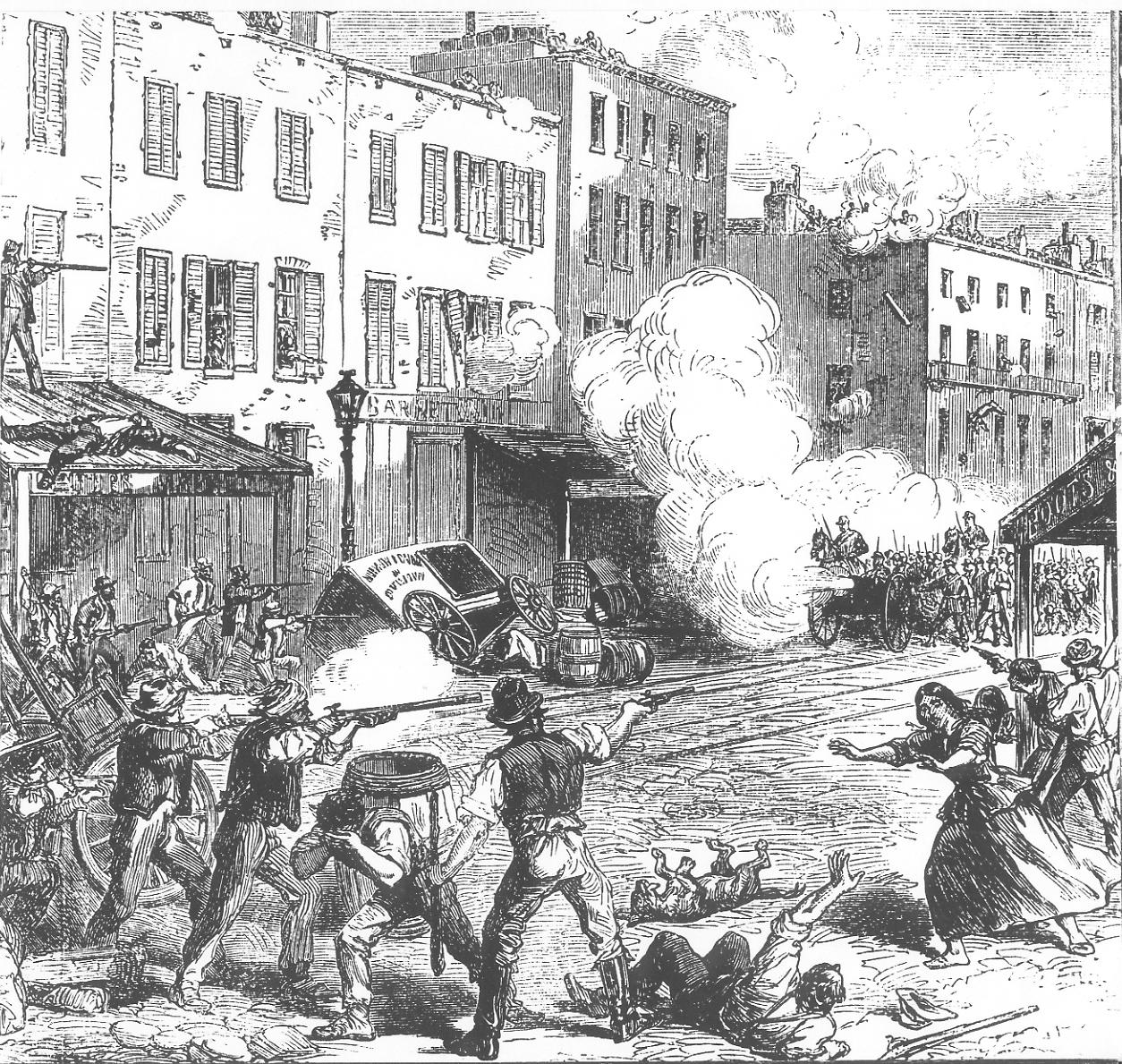

The police acted while civilians argued. They used the telegraph network (maintained by operators disguised as rioters) to track “plague spots” breaking out around the city. At one point, they sent 200 officers to halt 5,000 rioters pouring down Broadway. The police charged this horde at Bleecker Street, led by a grizzled old sergeant swinging his truncheon; one observer noted that for a while, “nothing was heard but the heavy thud of clubs falling on human skulls.”

Such battles taught the police a valuable lesson. They realized that 50 officers, moving together aggressively, could chase off 500 troublemakers lacking any organization. Once the police understood this, the week became a series of running confrontations, with clumps of rioters pinballing around Manhattan’s grid, colliding with tight units of police officers, scattering and re-forming.

The rioters never really had a chance. They achieved their only goal, pausing the draft lottery, within the first hours of their uprising. After that they had no organization, no leadership, no plan. The only question was how much damage they could do before being crushed.

By the middle of the week soldiers were streaming into the city, fighting a series of house-to-house battles in the East 20s, complete with rooftop snipers, artillery bombardments and cavalry charges. Whenever firearms were used, however, crowds grew more desperate and vicious. Policemen’s clubs did the best work.

As the police gained an upper hand, they were finally able to protect New York’s African-Americans. They evacuated the young survivors of the Colored Orphan Asylum. One witness recorded the searing scene, as “frightened little fugitives, fleeing from they scarce knew what” toddled to the foot of 35th Street under a strong guard.

Rioters retreated to tenement basements, dragging their wounded with them. The nature of the revolt — illegal and violent, fought without plan by illiterate laborers — meant that few left accounts. Their sympathizers spoke for them. Archbishop John J. Hughes refused to acknowledge the mobs’ guilt, referring to them as “the men of New York, who are now called in many of the papers rioters.” Individual priests bravely calmed crowds and protected victims, but the church leadership did nothing.

Meanwhile, native-born New Yorkers blamed all Irish Catholics (about a quarter of the city) for the riot, even though only a tiny fraction was involved. Nativists ignored the fact that many of the policemen battling the uprising had names like Kennedy and O’Brien.

By Friday the riots were over. The fighting left somewhere between 105 and 1,200 dead; even if the smaller number is correct, the draft riots killed twice as many people as the 1992 Los Angeles riots, in a city less than a quarter the size.

The uprising had little effect on conscription. Other states warned that if New York could dodge the draft by rioting, it would be unenforceable nationwide. Conscription resumed soon after, but the draft was smaller than is often believed. The image of a Union Army made up of conscripted foreigners is false; 92 percent of Union soldiers were volunteers, and immigrants were proportionally underrepresented in general.

After the war New Yorkers made a point of forgetting the riots. There are no historic markers at sites associated with the uprising. In a booming city obsessed with progress, no one wanted to linger on this shameful moment. It was easier to imagine Manhattan as an island of glittering shop windows, and ignore the piles of bricks that sat ready for throwing. (source: The New York Times; Jon Grinspan is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Virginia.)

No comments:

Post a Comment