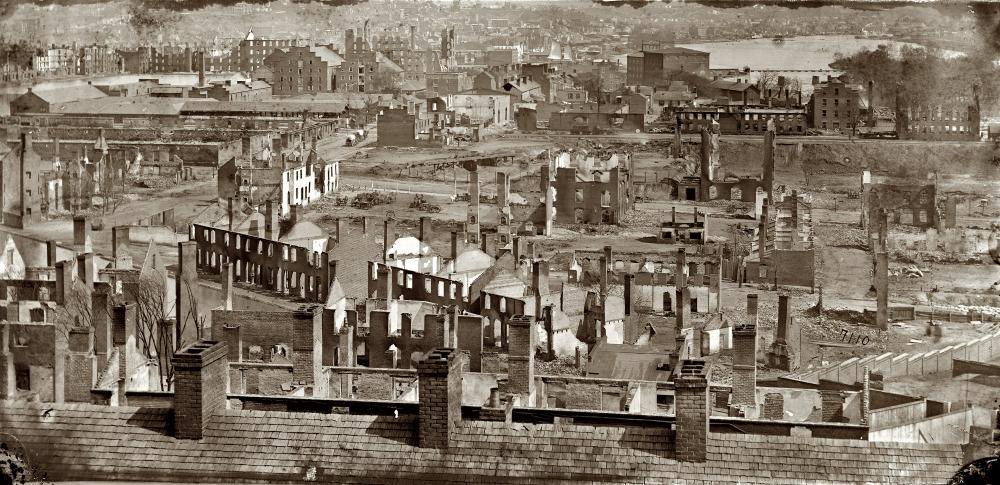

From the archives of The Economist (UK), "The fall of Richmond and its effect upon English commerce," Our [The UK Economist] coverage of the end of America's civil war, on 22 April 1865 -- United States -- THE fall of Richmond is one of the most striking events of modern history. On the one side the great hopes of the Confederates, their equally great efforts, the sympathy they have gained in Europe: on the other side, the undaunted courage of the Federals, their refusal to admit, even to their imagination, the possibility of real failure,—their accumulating power, which for many weeks past has seemed to concentrate like a gathering cloud about the capital of their enemies, give to the real event the intense but melancholy interest that belongs to the catastrophe of a tragedy. It is impossible not to feel a sympathy with the Confederates. There is an attraction in vanquished gallantry which appeals to the good side of human nature. But every Englishman at least will feel a kind of personal sympathy with the victory of the Federals.

They have won, as an Englishman would have won, by obstinacy. They would not admit the possibility of real defeat; they did not know that they were beaten; or, to speak more accurately, they knew that though they seemed to be beaten they were not: they felt that they had in them latent elements of conclusive vigour which, in the end, they should bring out, though they were awkward and slow in so doing. We may alter, perhaps, to suit this event, the terms which, in one of the greatest specimens of English narrative, the great English historian describes on a memorable occasion the conduct of Rome. "But there are moments when rashness is wisdom, and it may be that this was one of them; panic did not for a moment unnerve the iron courage of the American democracy, and their resolute will striving beyond. its present power created, as is the law of our nature, the power which it required."

But leaving history to deal in a becoming manner with the imaginative aspect of this great event, let us look at its present aspect in a business-like manner. The details of it are yet uncertain, and any conclusive judgment on minute results would be absurd. But, as far as we know, what does it amount to, and what will be its result?

It used to be said that Richmond was not essential to the Confederacy; that it was a nominal and accidental capital; that it was not even the original capital; that Virginia was but an outside State in a Confederacy with a vast interior; that even if this superficial outwork was lost, the war could be indefinitely protracted; that the fall of this exterior fortification would have scarcely affected the resistance of the provinces, upon which everything depended, And at the outset of the war when these words were used, they were doubtless substantially true. Subsequent events have in many respects confirmed them, and have in few tended to contradict them.

But now the case is altered. The loss of an outer fortification does not impair the resisting faculty, when it is lost early in the day—when its defenders have not spent upon it the resources which are needful to defend the citadel. It still appears to be true, that if sometime since when the Confederacy, had three armies unbroken—when no hostile army had penetrated their interior—when their organisation was as yet intact, its Government had retired from Richmond, the war would not have ceased on the evacuation. The task of pursuing three armies retiring in a vast and friendly country by converging lines would certainly have been difficult, and might not have been successful. Loose bodies of insurgents, if such there were, would then have had large armies upon which to support their accessory operations. But now the Confederacy have no such armies. What Lee may have saved, what Johnston may still command, we do not know; but we may say without fear that they are incalculably less than the armies of the Confederacy a year ago, that they cannot maintain as compact bodies even a defensive and retiring conflict with the eager armies of the North.

But without organised armies, can the Confederates be defended by loose insurgents and guerilla warfare, acting alone and without support? We believe that history affords no countenance to such an idea. A guerilla warfare requires the aid either of disciplined forces or of inaccessible territory. The history of the Spanish war shows conclusively that the guerilla resistance of the nation would have been useless without the regular resistance of the English army under the Duke of Wellington; the Spaniards enabled him to effect more with fewer troops, but they did little themselves. A territory like Arabia, a mountain chain like the Caucasus, can be defended by a few bodies of men with little discipline as well as by many more with discipline. Nature does so much that any sort of human force is sufficient to complete it. But the territory of the Confederacy though vast is penetrable: it is not a fortress, it is only a battlefield : it is a country in which a martial population, aided by effective armies, may well resist an invading enemy; but it is also a country from which even the most martial population may be brushed off with ease by diffused and disciplined forces.

Even under the most favourable circumstances a guerilla warfare by a nation of slaveowners must have unusual difficulties. The slaves cannot be relied on as a native peasantry can be relied on. It is said that Sherman on his march through Georgia always had good information regularly brought by negroes. We do not vouch for this as a fact, but it illustrates our meaning as an example. It is impossible that the existence of a slave class, which is not a part of the nation, which requires to be kept down by the nation, should not always be an impediment to the rising of the nation; and especially so in this case, when the invading army proclaims liberty to those slaves. We cannot expect a protracted guerilla resistance from a nation which has neither an inaccessible territory, nor a regular army, nor an attached peasant population.

But if the Confederacy cannot long defend itself, if the civil war must soon come to an end, what will be its effect on us? The war itself disturbed as much in its origin and much by its continuance, will it also disturb us much by its cessation?

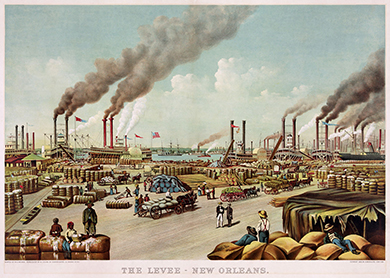

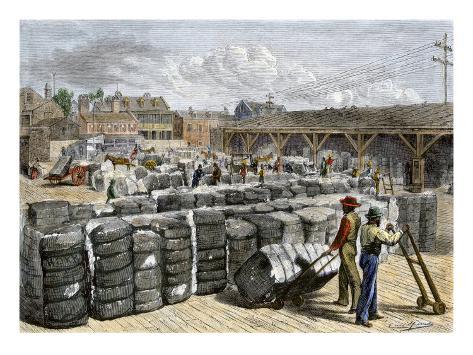

It is undeniable that the fall of Richmond, such as we have ascertained it to be, would have been of disastrous consequences to several branches of English commerce if it had happened six months ago. When cotton and its substitutes were weakly held at extravagant prices, the sudden occurrence of so great a catastrophe must have caused of itself many failures. So many slow and steady agencies all tending to produce a fall of price were then operating, that the addition of a single one of a striking nature might have produced lamentable results. A great panic in one class of articles would in a sensitive stale of the commercial world have produced a semi-panic in other articles. But now the case is different. Prices have greatly fallen. Whether they may have reached their lowest point exactly may lie argued, but they have fallen so low that no great further drop is possible or likely. Many weak holders have been cleared away, and the nominal price in consequence is firmer and more real than the nominal price of six months since. The peculiar circumstances affecting cotton, we explained in an elaborate article last week. We showed that even on the assumption that "the civil war in America must be near its close," there was no ground for thinking that cotton would experience a further fall, but rather a probability that the present fall had been too great and too sudden to be permanent. In fact, as so often happens, the effect of the defeat of the South has been discounted; the result of the expectation has been as great, if not greater, than the result of the event.

There is another circumstance of great importance. The world is getting "short of clothes," and especially of good clothes. When the war broke out great stores of cotton goods were found to be lying in warehouses at Manchester and elsewhere, and many persons were eager to raise the common cry of over-production: they fancied there was something anomalous and out of place in so vast an accumulation. But Mr Cobden, with that real perception of the facts of commerce which characterised his mind, immediately said, "No, there is no unnecessary accumulation, except in one or two particular markets, as India and China, and in other exceptional cases; we have not more goods on hand than we ought to have." In reality, a very considerable accumulation of stored manufactures is an attendant condition, an inevitable consequence, of the present vast and delicate division of labour. When everybody is working for everybody, everybody is injured by the mischances of everybody. An English middle class consumer is fed and clothed by an immense multiplicity of labourers; their numbers are considerable, and they are of several kinds. If any one important species of these labourers is impeded, we risk the loss of some article of prime necessity. But we insure against it. We keep a stock of each durable article so considerable that we have much to last for a long time, even if the means of producing it have by some casualty suddenly stopped. Some people say the world ought always to have "two years' stock" of clothes on hand, and now we bare nothing like it.

The effect of this will be very remarkable. When the American war broke out we had two years' stock on hand, and we lived on that till other sources of supply were opened and made effectual. The existence of that supply insured us then; its non-existence will insure us now. As we return to a usual and normal state of things, we shall tend to recur to our regular and habitual accumulation. We have not only now to clothe the world—we have to clothe it and something more. We have to make up our stock; to again create the guarantee fund, which shall insure us against any new calamities—against some deprivation of supply as sudden and as unlikely as an American civil war would have seemed five years ago. At that time any one who had prophesied the actual history of those five years would have been deemed a lunatic: our stored resources saved us then, and we must store them up again now to use them in like manner.

And this additional demand will gradually carry off an additional supply—especially if, as is likely, the clothes made with cheap material be better than the clothes made with dear material. There will be a capital demand for cotton and other goods, if once it is understood that the end is attained, that the bottom is reached, that the trader nearest the consumer—the small shopkeeper—had better supply himself at once. The small shops of the world are now only half supplied; if they once take to supplying themselves, the demand will be great.

As far, therefore, as the producing power of America is concerned, we do not think its revival, even if it should occur very rapidly, would derange our market, or affect us except beneficially. Nor, as far as its consuming power is concerned, can we cannot expect much from the conclusion of the war. Some sanguine persons fancy that we shall at once have a vast trade with the United States the moment they are reunited—the moment the war stops. But there is no ground for so thinking either as respects the South or the North. Some additional trade with both, of course, there will be, but not enough to affect Lombard street—to alter the demand for the capital of England. First, as to the North, its tariff cripples to an incredible extent all commerce with it. It has been spending largely and recklessly. It has been borrowing largely and recklessly. It has been misusing its currency. The repentance after these errors will be a time of strait and difficulty, and though under good management its splendid national resources are quite sufficient to cope with this difficulty, yet the difficulty is real and considerable. The additional immediate trade which we shall have with the North will not be of the first magnitude—will not affect the money market.

Nor will the trade with the South. The South is disorganised, and must long be disorganised. What the fate of its peculiar civilisation may be we cannot yet say, for there are no data, and any conclusion is only "one guess among many," one notion a little better perhaps than others, but without any solid ground of evidence. But so much is evident that great changes are in store for the South,—that it must pass through a social revolution,—that during the revolution it will not buy as it used to buy,—that after the revolution tastes will have changed, and it will not buy what it used to buy.

On the whole, therefore, the conclusion is, that though the catastrophe of the American war seems likely to happen more suddenly and more strikingly than could have been expected, yet its principal effect will have been already anticipated, and it will have less influence on prices and transactions than many events of less considerable magnitude. (source: The UK Economist)