The Congolese Ota Benga

As reported by the New York Times, "The Scandal at the Zoo," by Mitch Keller, on 6 August 2006-- WHEN New Yorkers went to the Bronx Zoo on Saturday, Sept. 8, 1906, they were treated to something novel at the Monkey House.

At first, some people weren’t sure what it was. It — he — seemed much less a monkey than a man, though a very small, dark one with grotesquely pointed teeth. He wore modern clothing but no shoes. He was proficient with bow and arrow, and entertained the crowd by shooting at a target. He displayed skill at weaving with twine, made amusing faces and drank soda.

The new resident of the Monkey House was, indeed, a man, a Congolese pygmy named Ota Benga. The next day, a sign was posted that gave Ota Benga’s height as 4 feet 11 inches, his weight as 103 pounds and his age as 23. The sign concluded, “Exhibited each afternoon during September.”

Visitors to the Monkey House that second day got an even better show. Ota Benga and an orangutan frolicked together, hugging and wrestling and playing tricks on each other. The crowd loved it. To enhance the jungle effect, a parrot was put in the cage and bones had been strewn around it. The crowd laughed as the pygmy sat staring at a pair of canvas shoes he had been given. “Few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions,” The New York Times wrote the next day, “and there could be no doubt that to the majority the joint man-and-monkey exhibition was the most interesting sight in Bronx Park.”

But the Ota Benga “exhibit” did not last. A scandal flared up almost immediately, fueled by the indignation of black clergymen like the Rev. James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. “Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes,” Mr. Gordon said. “We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.”

William Temple Hornaday, founder of the American conservation movement.

One hundred years later, the Ota Benga episode remains a perfect illustration of the racism that pervaded New York at the time. Mayor George McClellan, for example, refused to meet with the clergymen or to support their cause. For this he was congratulated by the zoo’s director, William Temple Hornaday, a major figure not only in the zoo’s history but also in the history of American conservation, who wrote to him, “When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage.”

The Bronx Zoo, which opened in 1899, was a young institution during the Ota Benga scandal. Those at the zoo today look back at the episode with a mixture of regret and resignation. “It was a mistake,” said John Calvelli, senior vice president for public affairs of the Wildlife Conservation Society, which owns and runs the zoo. “When you reflect on it, you realize that it was a moment in time. You have to look at the time in which it happened, and you try to understand why this would occur.”

That understanding may deepen with a recent spike in interest in Ota Benga, who died in March 1916 when he shot himself in the heart. His story has inspired writers, artists and musicians, and there is even an effort to exhume his remains from a cemetery in Lynchburg, Va., where he spent the last six years of his life, and return them to Congo.

“This was his wish,” said Dibinga wa Said, a Congolese involved in the exhumation campaign. “He wanted to go home.”

From the Bush to the Bronx

Ota Benga had already lived an eventful life by the time he arrived in the Bronx. According to the 1992 book “Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo,” by Phillips Verner Bradford and Harvey Blume, he was a survivor of a pygmy slaughter carried out by the Force Publique, a vicious armed force in service to Leopold II, the king of Belgium and the ruler of what was then called Congo Free State. Among the dead were Ota Benga’s wife and two children.

The killers sold him into slavery to a tribe called the Baschilele. He was in the slave market when his deliverance appeared one day in the form of Samuel Phillips Verner, 30, an Africa-obsessed explorer, anthropologist and missionary from South Carolina (and a grandfather of Dr. Bradford, the author).

Mr. Verner had been hired to take some pygmies and other Africans back to St. Louis for the extensive “anthropology exhibit” at the 1904 World’s Fair. There, for the edification of American fairgoers, they and representatives of other aboriginal peoples, like Eskimos, American Indians and Filipino tribesmen, would live in replicas of their traditional dwellings and villages.

After examining Ota Benga and being particularly pleased by his teeth, which had been filed to sharp points in the manner common among his people, Mr. Verner bought him from his captors and, along with several other pygmies and a few other Africans, took him to St. Louis. When the fair was over, he took them all back to Africa as promised.

Ota Benga was unable to make a successful transition to his original way of life, and continued to spend a lot of time with Mr. Verner as the anthropologist pursued his interests in Africa, which included the collection of artifacts and animal specimens. Their friendship grew, and Ota Benga asked Mr. Verner to return with him to “the land of the muzungu” — the land of the white man. The blond South Carolinian and the pygmy arrived back in New York in August 1906.

Their first stop, as Dr. Bradford and Mr. Blume recount in their book, was the American Museum of Natural History, whose director, Hermon Bumpus, agreed to store not just Mr. Verner’s cargo of collectibles, including a couple of chimpanzees, but — temporarily, at least — Ota Benga himself. Mr. Verner, who was broke, left for the South to try to raise some money, and the pygmy’s residency in the Museum of Natural History began. He was given a place to sleep and seems to have been free to roam the museum. Mr. Bumpus bought him a white duck suit.

Before long, though, the African became difficult to control. Among other things, he threw a chair at Florence Guggenheim, the philanthropist, and almost hit her in the head. Fed up, Mr. Bumpus suggested that Mr. Verner explore the possibilities at the zoo. Hornaday, the zoo’s director, was receptive, agreeing to lodge not just Mr. Verner’s animals but Ota Benga, too. Toward the end of August, the defining chapter in the pygmy’s strange life had begun.

Degradation and Darwin

Ota Benga was free to wander the zoo as he pleased. Sometimes he helped the animal keepers with their jobs. In fact, Hornaday described the African as being “employed” by the zoo, though there is no record he was ever paid. He spent a lot of time at the Monkey House, caring for Mr. Verner’s one surviving chimp and bonding as well with an orangutan named Dohong.

Contrary to common belief, Ota Benga was not simply placed in a cage that second weekend in September and put on display. As Dr. Bradford and Mr. Blume point out, the process was far subtler. Since he was already spending much time inside the Monkey House, where he was free to come and go, it was but a small step to encourage him to hang his hammock in an empty cage and start spending even more time there. It was but another small step to give him his bow and arrows, set up a target and encourage him to start shooting. This was the scene that zoogoers found at the Monkey House on the first day of the Ota Benga “exhibit.”

The next day, word was out. The headline in The New York Times read: “Bushman Shares a Cage With Bronx Park Apes.” Thousands went to the zoo that day to see the new attraction, to watch him carry on so amusingly, often arm in arm, with Dohong the orangutan.

But the end came quickly. Confronted with the protests of the Colored Baptist Ministers’ Conference, Mr. Hornaday suspended the exhibit that Monday afternoon.

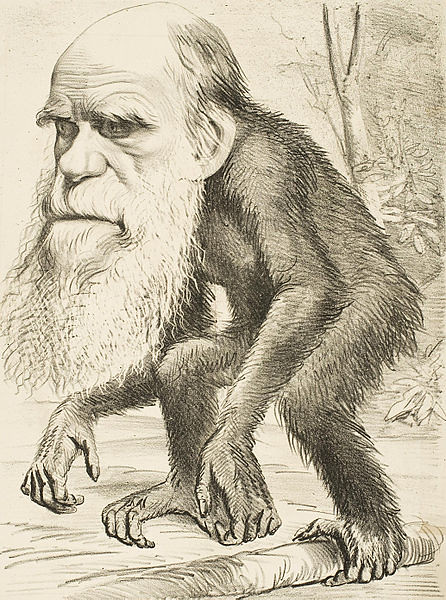

To the black ministers and their allies, the message of the exhibit was clear: The African was meant to be seen as falling somewhere on the evolutionary scale between the apes with which he was housed and the people in the overwhelmingly white crowds who found him so entertaining.

“The person responsible for this exhibition,” said the Rev. R. S. MacArthur, a white man who was pastor of the Calvary Baptist Church, “degrades himself as much as he does the African. Instead of making a beast of this little fellow, we should be putting him in school for the development of such powers as God gave him.”

It was not just racism that offended the clergymen. As Christians, they did not believe in Darwin, and the Ota Benga exhibit, as Mr. Gordon of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum said, “evidently aims to be a demonstration of Darwin’s theory of evolution.”

“The Darwinian theory is absolutely opposed to Christianity, and a public demonstration in its favor should not be permitted,” Mr. Gordon said.

As for the press, The Evening Post reported that Ota Benga, according to the zoo’s animal keepers, “has a great influence with the beasts — even with the larger kind, including the orang-outang with whom he plays as though one of them, rolling around the floor of the cages in wild wrestling matches and chattering to them in his own guttural tongue, which they seem to understand.”

The New York Times wrote in an editorial: “Not feeling particularly vehement excitement ourselves over the exhibition of an African ‘pigmy’ in the Primate House of the Zoological Park, we do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter. Still, the show is not exactly a pleasant one, and we do wonder that the Director did not foresee and avoid the scoldings now aimed in his direction.” The editorial added, “As for Benga himself, he is probably enjoying himself as well as he could anywhere in his country, and it is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation he is suffering.”

The New York Globe printed a letter from a reader that said: “I lived in the south several years, and consequently am not overfond of the negro, but believe him human. I think it a shame that the authorities of this great city should allow such a sight as that witnessed at the Bronx Park — a negro boy on exhibition in a monkey cage.”

And The New York Daily Tribune, evincing little interest in facts, wrote of Ota Benga’s past: “His first wife excited the hunger of the rest of the tribe, and one day when Ota returned from hunting he learned that she had passed quietly away just before luncheon and that there was not so much as a sparerib for him.”

Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an “ethnological exhibit.” In a letter to the mayor, he defended “my action in placing Dr. Verner’s very interesting little African where the people of New York may see him without annoyance or discomfort to him.” In another letter, he said that he and Madison Grant, the secretary of the New York Zoological Society — who 10 years later would publish the racialist tract “The Passing of the Great Race” — considered it “imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to” by the black clergymen.

The public, at any rate, had not yet had its fill of Ota Benga, whose name was now a household one. Though no longer on official display, the African was still living at the zoo and spending time with his primate friends in the Monkey House. On Sunday, Sept. 16, 40,000 people went to the zoo, and everywhere Ota Benga went that day, The Times reported, the crowds pursued him, “howling, jeering and yelling.”

The newspaper reported, “Some of them poked him in the ribs, others tripped him up, all laughed at him.”

Suicide, and MySpace

Toward the end of September, arrangements were made for Ota Benga to live at the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. Eventually he was sent to the asylum’s facility in eastern Long Island. Then, in January 1910, Mr. Gordon arranged for the pygmy to move to Lynchburg, where he had already spent a semester at a Baptist seminary.

In Lynchburg, Ota Benga had his teeth capped and became known as Otto Bingo. He spent a lot of time in the woods, hunting with bow and arrow, and gathering plants and herbs. He did odd jobs and worked in a tobacco factory. He became friendly with the poet Anne Spencer, who lived in Lynchburg, and through her met both W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington.

No one can be absolutely sure why Ota Benga killed himself that afternoon in March 1916. Dr. Dibinga, the Congolese who wants to return the pygmy’s remains to Congo, agrees with the view expressed in a Lynchburg newspaper report of the time: “For a long time the young negro pined for his African relations, and grew morose when he realized that such a trip was out of the question because of the lack of resources.” Mr. Verner himself wrote that Ota Benga “probably succumbed only after the feeling of utter inassimilability overwhelmed his brave little heart.”

“Congo is a very important area for us, and we’ve been there for many, many years,” he said. “The way we memorialize the Ota Benga experience is by making sure that the place where Ota Benga came from remains a place where his people can continue to live.”

After 100 years, Ota Benga seems to be having the last word. His name has been adopted by the Ota Benga Alliance for Peace, Healing and Dignity in Congo and by a Houston-based collective of African-American artists called Otabenga Jones and Associates. This spring he was the subject of a three-day conference in Lynchburg that included lectures, readings and an ecumenical service. Dr. Dibinga and other participants in that conference are hoping to have an even bigger one next year, with Congolese pygmies in attendance.

In 2001, “Ode to Ota Benga,” a “historical lecture with piano improvisations” by the performer and composer Lester Allyson Knibbs, was presented at the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance. In 2003, the Brooklyn-based alternative band Piñataland recorded the song “Ota Benga’s Name,” drawing many of the lyrics from a poem that appeared in The New York Times on Sept. 19, 1906: “In this land of foremost progress/ In this wisdom’s ripest age/ We have placed him in high honor in a monkey’s cage.”

To make the return of Ota Benga complete, he even has a page at www.myspace .com. The “About Me” section quotes the sign that hung briefly at the Monkey House, including its final phrase, “Exhibited each afternoon during September.” (source: The New York Times, Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company)

Quantum Binary Signals

ReplyDeleteGet professional trading signals delivered to your cell phone daily.

Start following our signals NOW and profit up to 270% a day.