This site is for educational purposes. Slavery in the new world from Africa to the Americas.

Saturday, March 30, 2013

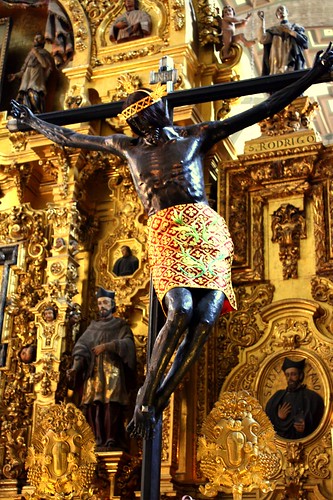

Jesus Was Lynched

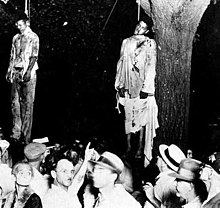

As reported by Truthdig, "Jesus Was Lynched," by Mel White, on 23 December 2011 -- For more than 40 years I’ve been moved and provoked by the writings of James Cone, Union Seminary’s distinguished professor of systematic theology. While reading his newest book, “The Cross and the Lynching Tree,” however, I felt grief and anger on a whole new scale. I felt grief for the nearly 5,000 African-American men, women and children who were lynched between 1880 and 1940, and anger that during that 60-year holocaust, white preachers, evangelists and theologians didn’t even notice. No author has ever made me more ashamed to be a white American Christian and at the same time no author has ever given me a more dramatic example of the sustaining power of the cross.

All my life I had been taught that the cross was at the heart of my Christian faith. It has been a long time since I was deeply moved by it. “The Cross and the Lynching Tree” helped me experience the cross on a far more visceral level. Cone says it simply: Jesus was lynched. He makes the connection between the crucifixion of Jesus and the lynching of African-Americans. He explains why understanding that connection is vital to understanding the meaning of the cross:

“As Jesus was an innocent victim of mob hysteria and Roman imperial violence, many African-Americans were innocent victims of white mobs, thirsting for blood in the name of God and in defense of segregation, white supremacy, and the purity of the Anglo-Saxon race. Both the cross and the lynching tree were symbols of terror, instruments of torture and execution, reserved primarily for slaves, criminals, and insurrectionists—the lowest of the low in society. Both Jesus and blacks were publicly humiliated, subjected to the utmost indignity and cruelty. They were stripped, in order to be deprived of dignity, then paraded, mocked and whipped, pierced, derided and spat upon, and tortured for hours in the presence of jeering crowds for popular entertainment. In both cases, the purpose was to strike terror in the subject community. It was to let people know that the same thing would happen to them if they did not stay in their place.”

During his decades of research, Cone found, incredibly, no sermons, lectures, books or articles by white preachers, evangelists or theologians linking what happened on the cross to what happened on the lynching tree—not even when lynching was at its peak.

Cone is particularly saddened that Reinhold Niebuhr, perhaps the most influential theologian and ethicist of the 20th century, “failed to connect the cross and its most vivid reenactment in his time.” Cone, who is black and grew up in segregated Arkansas, is rightfully aggrieved when he describes the silence of Christian leaders during and after the lynching years. “To reflect on this failure,” Cone warns, “is to address a defect in the conscience of white Christians and to suggest why African-Americans have needed to trust and cultivate their own theological imagination.”

Story after heartbreaking story, Cone walks us through those tragic and shameful years when thousands of black Americans were dragged from their homes and families, raped, tortured, disemboweled, castrated, burned and/or hanged by white Americans. Often those same white Americans were quoting Scripture while silhouetted by flaming crosses. Here are just two of the stories Cone tells to illustrate the horror of the lynching tree:

AsIn 1918, when a white mob in Valdosta, Ga., couldn’t find Haynes Turner (who was guilty of nothing more than being black) the sheriff arrested his wife instead. Mary Turner was eight months pregnant. When she insisted that her husband was innocent, she was “stripped, hung upside down by the ankles, soaked with gasoline and roasted to death. In the midst of this torment, a white man opened her swollen belly with a hunting knife and her infant fell to the ground and was stomped to death.”

In 1955, Emmett Louis “Bo” Till, a 14-year-old African-American from Chicago, was kidnapped from his grandparents’ Mississippi home because (or so the rumor went) he had dared to whistle at Carolyn Bryant, a 21-year old white woman, and moments later said “Bye, baby” as she left a local store. At 2 a.m. Bryant’s husband and his half-brother dragged Till to a barn where one of the boy’s eyes was gouged out. He was tortured, beaten beyond recognition, shot in the head, tied to a heavy gin fan and dropped into the Tallahatchie River. The two men were arrested, tried and found not guilty of the crime.

Cone documents in grim detail the unimaginable mental and physical suffering black Americans experienced during those lynching years. But instead of giving up on God, those who suffered embraced their Christian faith with new zeal. Cone turns to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to help us understand how great suffering, paradoxically, can lead to even greater faith. In his “darkest hours” during the Montgomery bus boycott, King’s own experience of suffering lead him to conclude that we do not know what we truly believe or what our theology is worth until “our highest hopes are turned into shambles of despair” or “we are victims of some tragic injustice and some terrible exploitation.” Cone summarizes the mystery of faith that grew stronger during the lynching years:

“Black faith emerged out of black people’s wrestling with suffering, the struggle to make sense out of their senseless situation, as they related their own predicament to similar stories in the Bible. On the one hand, faith spoke to their suffering, making it bearable, while on the other hand, suffering contradicted their faith, making it unbearable. That is the profound paradox inherent in black faith, the dialectic of doubt and trust in the search for meaning, as blacks ‘walk[ed] through the valley of the shadow of death.’ ”

“The Cross and the Lynching Tree” also explores the connection between faith and art, through the music, poetry and prose of those who suffered. Cone asks: “How did ordinary blacks, like my mother and father, survive the lynching atrocity and still keep together their families, their communities and not lose their sanity?” He answers that question simply: “Both black religion and the blues offered sources of hope that there was more to life than what one encountered daily in the white man’s world.”

There was no opportunity for black Americans to protest, let alone defend themselves from the violence that permeated their lives. In public, where a black man could be lynched for looking a white man in the eye, they had to play the subservient coward. But on Saturday nights, by singing the blues in the privacy of their “juke joints” where the whole community gathered to dance, drink, clap, stomp and “hollar,” these “cowards” expressed their courage and their determination to overcome. Those nights brought a measure of joy and a lot of relief to black Americans. To the white man all that “noise” must have seemed tribal and orgiastic. But if those same white men had been capable of truly listening, they would have realized that the poetry of the blues was in fact restoring the souls of black Americans and renewing their determination to resist despair.

As a child, Cone remembers hearing the blues echoing at night from “Sam’s Place” near his home in Arkansas. The author recalls tapping his feet and moving his body to the sounds of B.B. King’s “Rock Me Baby” and Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man.” There is no question, however, that Billie Holiday holds a special place for the author. In 1939, on the stage of New York’s Café Society, Holiday sang “Strange Fruit,” the first of many songs that would help mobilize the civil rights movement. Time magazine called “Strange Fruit” “the best song of the century,” and Holiday “history’s greatest jazz singer.” The song was written by Abel Meeropol, the white Jewish communist who later adopted the two sons of convicted spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg after their execution. “Strange Fruit” was inspired by an appalling photo Meeropol saw of a lynching in Mississippi:

“Southern trees bear strange fruit, Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze, Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South, The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh, Then the sudden smell of burning flesh …”

On Sundays a different kind of music was heard. Cone uses the familiar spiritual “Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen” to show how the black poetry of those lynching years reflected both suffering and certainty. The spiritual begins with a mournful lament but ends with an almost inexplicable shout of praise: “Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen. Nobody knows my sorrow. Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen … Glory Hallelujah!”

Black poets and musicians brought hope in times of despair. They were not blind to the fact that white Christians were in large part the cause of their suffering. With scathing sarcasm, black poet Walter Everette Hawkins called lynching “A Festival of Christendom” alongside the festive days of Christmas and Easter:

“And so the Christian mob did turn from prayer to rob, to lynch and burn.

A victim helplessly he fell to tortures truly kin to hell;

They bound him fast and strung him high. They cut him down lest he should die

Before their energy was spent in torturing to their heart’s content.

They tore his flesh and broke his bones and laughed in triumph at his groans;

They chopped his fingers, clipped his ears and passed them round as souvenirs.

The bored hot irons in his side and reveled in their zeal and pride;

They cut his quivering flesh away and danced and sang as Christians may … ”

In spite of their anger at white Christians, they spoke of Jesus’ life and death with increasing reverence. Black poet Countee Cullen writes, “How Calvary in Palestine, extending down to me and mine, was but the first leaf in a line of trees on which a Man should swing … ” Cone points out that in this poem Cullen is claiming “that Christ, poetically and religiously, was symbolically the first lynchee,” and by this close association with Jesus “turned lynch victims into martyrs.” Cullen wrote, “The South is crucifying Christ again,” and this time “he’s dark of hue.” According to Cone, Cullen and many of his fellow poets and musicians could not help but see “ … the liberating power of the ‘Black Christ’ for suffering black people.”

“Ordinary blacks” survived those lynching years, Cone says, because their Jesus too had been lynched. He too had suffered exactly as they were suffering. They were not alone when they walked into the valley of death because Jesus walked that way before them. “Jesus walked this lonesome valley,” a spiritual begins, “He had to walk it by himself. Nobody else could walk it for him. He had to walk it by himself.” African-American Christians were absolutely certain the Christ who died on a cross understood their suffering and would see them through it.

Cone understands that although black art and music helped foment the civil rights movement, “ … the blues and the juke joint did not lead to an organized political resistance against white supremacy. But one could correctly say that the spirituals and the church, with Jesus’ cross at the heart of its faith, gave birth to the black freedom movement that reached its peak in the civil rights era during the 1950s and 1960s. The spirituals were the soul of the movement, giving people courage to fight, and the church was its anchor, deepening its faith in the coming freedom for all.”

Cone makes it clear that the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s—with spirituals as its soul and the church as its anchor—saw an end to segregation but not to white supremacy. At its heart, “The Cross and the Lynching Tree” is a powerful indictment of white supremacy, past and present, and a challenge to white Americans to have “the courage to confront the great sin and ongoing legacy of white supremacy with repentance and reparation.”

The lynching of black Americans is still taking place in the 21st century. Cone targets America’s criminal justice system “ … where nearly one-third of black men between the ages of 18 and 28 are in prisons, jails, on parole or waiting for their day in court.” Cone continues:

“Nearly one-half of the more than 2 million people in prisons are black. That is 1 million black people behind bars, more than in colleges. Through private prisons and the ‘war against drugs’ whites have turned the brutality of their racist legal system into a profit-making venture for dying white towns and cities throughout America. … Nothing is more racist in America’s criminal justice system than its administration of the death penalty. America is the only industrialized country in the West where the death penalty is still legal. The death penalty is primarily reserved, though not exclusively, for people of color, and white supremacy shows no signs of changing it. That is why the term ‘legal lynching’ is still relevant today. One can lynch a person without a rope or tree.”

I am a white American. What questions should I ask myself about living in a nation still permeated by white supremacy? What questions should I ask myself about living in a mostly white neighborhood, attending a mostly white church and hanging out with mostly white friends? Cone states unequivocally that Jesus calls us to confront white supremacy. “I believe,” Cone writes, “that the cross placed alongside the lynching tree can help us to see Jesus in America in a new light, and thereby empower people who claim to follow him to take a stand against white supremacy and every kind of injustice.”

“The Cross and the Lynching Tree” also transcends the topic of lynching and the suffering of African-Americans. Cone asks his readers to see all suffering and oppression in light of the promise of the cross. Therefore—and please forgive this personal aside—his “every kind of injustice” includes the injustice faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans. What was Matthew Shepard’s death but a lynching? All the elements are present. Shepard was harassed, kidnapped, driven to a remote country area, robbed, pistol-whipped, tortured, tied to a fence and left to die. Brandon Teena, a 21-year-old trans man who was raped and murdered, is just one example of dozens of forgotten trans people who are lynched every year. And in some ways Tyler Clementi, Jamey Rodemeyer and all the other gay teens and young people who have committed suicide because of bullying and harassment are lynching victims.

My son once asked me, “How can you still be a Christian, Dad, after what the church has done to you?” Suddenly we’re back to the same mystery we encountered with black Christians during the lynching years. Cone quotes the Apostle Paul to describe this mystery: “St. Paul said that the ‘word of the cross is foolishness’ to the intellect and a ‘stumbling block’ to established religion. The cross is a paradoxical religious symbol because it inverts the world’s value system with the news that hope comes by way of defeat, that suffering and death do not have the last word, that the last shall be first and the first last.” I believed that Jesus was with me during the attacks by Bible-quoting Christians, during the disappearance of most of my old friends and clients, and during the aversive therapies, the electric shock and the exorcisms by well-meaning Christians who tried to rid me of the “demon of homosexuality.” And in my lowest moments when I genuinely longed for death, I knew that Jesus would walk with me through that valley as well.

Black Americans were victims of white Christian bigotry as gay Americans are victims of straight Christian bigotry. Please don’t think for a moment that I am comparing my suffering or the suffering of the LGBT community to the suffering of African-Americans during the lynching years. I am not. But in the struggle between faith and oppression, and sensing Jesus’ presence during my own suffering, I feel solidarity with my African-American family whose faith in the “old rugged cross” was the key to surviving the lynching tree.

Here is the danger: To say that Jesus stands with me in my suffering is far too simple. My redemption doesn’t come that easily. There’s something in the cross that says this is not just about my “salvation” but about the “salvation” of all those who suffer injustice and inequality. The cross warns and welcomes. It warns me that if I confront white supremacy, homophobia or injustice of any kind, I could end up being lynched. And the cross welcomes me to that great company of the committed who believed its promise that “death is not the end but the beginning of life.”

Cone reminds us that “ … it takes a special kind of imagination to understand the truth of the cross. … The Gospel of Jesus is not a rational concept to be explained in a theory of salvation, but a story about God’s presence in Jesus’ solidarity with the oppressed which led to his death on the cross. … What is redemptive is the faith that God snatches victory out of defeat, life out of death and hope out of despair, as revealed in the biblical and black proclamation of Jesus’ resurrection.”

[source: Truthdig -- The Rev. Mel White is co-founder of Soulforce and the author of “Stranger at the Gate: To Be Gay and Christian in America” and “Religion Gone Bad: The Hidden Dangers of the Christian Right.” --- © 2013 Truthdig, LLC. All rights reserved.]

Friday, March 29, 2013

James Cone: The Cross & The Lynching Tree

As reported in Truthdig, "James Cone’s Gospel of the Penniless, Jobless, Marginalized and Despised," by Chris Hedges, on 9 January 2012 -- “The Cross and the Lynching Tree are separated by nearly two thousand years,” James Cone writes in his new book, “The Cross and the Lynching Tree.” “One is the universal symbol of the Christian faith; the other is the quintessential symbol of black oppression in America. Though both are symbols of death, one represents a message of hope and salvation, while the other signifies the negation of that message by white supremacy. Despite the obvious similarities between Jesus’ death on the cross and the death of thousands of black men and women strung up to die on a lamppost or tree, relatively few people, apart from the black poets, novelists, and other reality-seeing artists, have explored the symbolic connections. Yet, I believe this is the challenge we must face. What is at stake is the credibility and the promise of the Christian gospel and the hope that we may heal the wounds of racial violence that continue to divide our churches and our society.”

So begins James Cone, perhaps the most important contemporary theologian in America, who has spent a lifetime pointing out the hypocrisy and mendacity of the white church and white-dominated society while lifting up and exalting the voices of the oppressed. He writes out of his experience as an African-American growing up in segregated Arkansas and his close association with the Black Power movement. But what is more important is that he writes out of a deep religious conviction, one I share, that the true power of the Christian gospel is its unambiguous call for liberation from forces of oppression and for a fierce and uncompromising condemnation of all who oppress.

Cone, who teaches at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, writes on behalf of all those whom the Salvadoran theologian and martyr Ignacio Ellacuría called “the crucified peoples of history.” He writes for the forgotten and abused, the marginalized and the despised. He writes for those who are penniless, jobless, landless and without political or social power. He writes for gays, lesbians, bisexuals and those who are transgender. He writes for undocumented farmworkers toiling in misery in the nation’s agricultural fields. He writes for Muslims who live under the terror of war and empire in Iraq and Afghanistan. And he writes for us. He understands that until white Americans can see the cross and the lynching tree together, “until we can identify Christ with a ‘recrucified’ black-body hanging from a lynching tree, there can be no genuine understanding of Christian identity in America, and no deliverance from the brutal legacy of slavery and white supremacy.”

“In the deepest sense, I’ve been writing this book all my life,” he said of “The Cross and the Lynching Tree” when we spoke recently. “I put my whole being into it. And did not hold anything back. I didn’t choose to write it. It chose me.

Dr. James Cone

“I started reading about lynching, and reading about the historical situation of the crosses in Rome in the time of Jesus, and then my question was how did African-Americans survive and resist the lynching terror. How did they do it? [Nearly 5,000 African-American men, women and children were lynched in the United States between 1880 and 1940.] To live every day under the terror of death. I grew up in Arkansas. I know something about that. I watched my mother and father deal with that. But the moment I read about it, historically, I had to ask, how did they survive, how did they keep their sanity in the midst of that terror? And I discovered it was the cross. It was their faith in that cross, that if God was with Jesus, God must be with us, because we’re up on the cross too. And then the other question was, how could white Christians, who say they believe that Jesus died on the cross to save them, how could they then turn around and put blacks on crosses and crucify them just like the Romans crucified Jesus? That was an amazing paradox to me. Here African-Americans used faith to survive and resist, and fight, while whites used faith in order to terrorize black people. Two communities. Both Christian. Living in the same faith. Whites did lynchings on church grounds. How could they do it? That’s where [my] passion came from. That’s where the paradox came from. That’s where the wrestling came from.

“Many Christians embrace the conviction that Jesus died on the cross to redeem humankind from sin,” he said. “Taking our place, they say, Jesus suffered on the cross and gave his life as a ransom for many. The cross is the great symbol of the Christian narrative of salvation. Unfortunately, during the course of 2,000 years of Christian history, the symbol of salvation has been detached from the ongoing suffering and oppression of human beings, the crucified people of history. The cross has been transformed into a harmless, non-offensive ornament that Christians wear around their necks. Rather than reminding us of the cost of discipleship, it has become a form of cheap grace, an easy way to salvation that doesn’t force us to confront the power of Christ’s message and mission.”

Cone’s chapter on Reinhold Niebuhr, the most important Christian social ethicist of the 20th century and a theologian whose work Cone teaches, exposes Niebuhr’s blindness to and tacit complicity in white oppression. Slavery, segregation and the terror of lynching have little or no place in the theological reflections of Niebuhr or any other white theologian. Niebuhr, as Cone points out, had little empathy for those subjugated by white colonialists. Niebuhr claimed that North America was a “virgin continent when the Anglo-Saxons came, with a few Indians in a primitive state of culture.” He saw America as being elected by God for the expansion of empire and, as Cone points out, “he wrote about Arabs of Palestine and people of color in the Third World in a similar manner, offering moral justification for colonialism.”

Cone reprints a radio dialogue between Niebuhr and writer James Baldwin that took place after the September 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., that killed four girls. Niebuhr, who spoke in the language of moderation that infuriated figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Baldwin, was disarmed by Baldwin’s eloquence and fire.

Baldwin said: The only people in this country at the moment who believe either in Christianity or in the country are the most despised minority in it. … It is ironical … the people who were slaves here, the most beaten and despised people here … should be at this moment … the only hope this country has. It doesn’t have any other. None of the descendants of Europe seem to be able to do, or have taken it on themselves to do, what Negros are now trying to do. And this is not a chauvinistic or racial outlook. It probably has something to do with the nature of life itself. It forces you, in any extremity, any extreme, to discover what you really live by, whereas most Americans have been for so long, so safe and so sleepy, that they don’t any longer have any real sense of what they live by. I think they really think it may be Coca-Cola.

“If Niebuhr could ignore it, there must be something defective in that faith itself,” Cone said. “If it weren’t defective, then they wouldn’t put black people on crosses. Niebuhr wouldn’t have been silent about it. I look around and see the same thing happening today in the prison industrial complex. You can lynch people by more than just hanging them on the tree. You can incarcerate them. How long will this terror last? I’m Christian. Suffering gives rise to faith. It helps you deal with it. But at the same time, suffering contradicts the faith that it gave rise to. It is like Jacob wrestling with the angel. I can’t give up with the wrestling.”

Cone wrote his doctoral dissertation on the Swiss theologian Karl Barth. But Barth, he admits, never moved him deeply. Cone found his inspiration in the black church, along with writers such as Baldwin, Albert Camus and Richard Wright, as well as the great blues artists of his youth. These artists and writers, not the white theologians, he said, gave him “a sense of awe.” He saw that “for most blacks it was the blues and religion that offered the chief weapons of resistance.” It was religion and the blues that “offered sources of hope that there was more to life than what one encountered daily in the white man’s world.” In the words of great poets and writers, in the verses of the great blues singers and in the thunderous services of the black church, not in the words of white theologians, Cone discovered those who were able to confront the bleak circumstances of their lives and yet defy fate and suffering to make the most of what little life had offered them. He had through these connections found his own voice, one that was powerfully expressed in his first work, the 1969 manifesto “Black Theology & Black Power.” Cone understood that “when people do not want to be themselves, but somebody else, that is utter despair.” And he knew that his faith “was the one thing white people could not control or take away.”

He quotes the bluesman Robert Johnson:

I got to keep movin’, I got to keep movin’,

Blues fallin’ down like hail

And the day keeps on worrin’ me,

There’s a hellhound on my trail.

“I like people who talk about the real, concrete world,” he said. “And unless I can feel it in my gut, in my being, I can’t say it. The poor help me to say it. The literary people help me to say it—Baldwin is my favorite. Martin King is the next. Malcolm is the third element of my trinity. The poets give me energy. Theologians talk about things removed, way out there. They talk to each other. They give each other degrees. The real world is not there. So that is why I turn to the poets. They talk to the people.

“Being Christian is like being black,” Cone said. “It’s a paradox. You grow up. You wonder why they treat you like that. And yet at the same time my mother and daddy told me ‘don’t hate like they hate. If you do, you will self-destruct. Hate only kills the hater, not the hated.’ It was their faith that gave them the resources to transcend the brutality and see the real beauty. It’s a mystery. It’s a mystery how African-Americans, after two and half centuries of slavery, another century of lynching and Jim Crow segregation, still come out loving white people. Now, most white people don’t think I love them, but I do. They always feel strange when I say that. You see, the deeper the love, the more the passion, especially when the one you love hurt you. Your brothers and sisters, and yet they treat you like the enemy. The paradox is, is that in spite of all that, African-Americans are the only people who’ve never organized to take down this nation. We have fought. We have given our lives. No matter what they do to us, we still come out whole. Still searching for meaning. I think the resources for that are in the culture and in the religion that is associated with that. That faith and that culture, it was the blues of the spiritual; that faith and that culture gives African-Americans a sense that they are not what white people say they are.”

Cone sees the cross as “a paradoxical religious symbol because it inverts the world’s value system with the news that hope comes by way of defeat, that suffering and death do not have the last word, that the last shall be first and the first last.” This idea, he points out, is absurd to the intellect, “yet profoundly real in the souls of black folk.” The crucified Christ, for those who are crucified themselves, manifests “God’s loving and liberating presence in the contradictions of black life—that transcendent presence in the lives of black Christians that empowered them to believe that ultimately, in God’s eschatological future, they would not be defeated by the ‘troubles of the world,’ no matter how great and painful their suffering.” Cone elucidates this paradox, what he calls “this absurd claim of faith,” by pointing out that to cling to this absurdity was possible only when one was shorn of power, when one was unable to be proud and mighty, when one understood that he was not called by God to rule over others. “The cross was God’s critique of power—white power—with powerless love, snatching victory out of defeat.”

“It’s like love,” he said. “It’s something you cannot articulate. It’s self-evident in its own living. And I’ve seen it among many black Christians who struggle, particularly in the civil rights movement. They know they’re going to die. They know they’re not going to win in the obvious way of winning. But they have to do what they gonna do because the reality that they encounter in that spiritual moment, that reality is more powerful than the opposition, than that which contradicts it. People respond to what empowers them inside. It makes them know they are somebody when the world treats them as nobody. When you can do that, when you can act out of that spirit, then you know there is a reality that is much bigger than you. And that’s, that’s what black religion bears witness to in all of its flaws. It bears witness to a reality that empowers people to do that which seems impossible. I grew up with that. I really don’t ever remember wishing I was white. I may have, but I really don’t remember. It’s because the reality of my own community was so strong, that that was more important than the material things I saw out there. Their [African-Americans’] music, their preaching, their loving, their dancing—everything was much more interesting.

“How do a people know that they are not what the world says they are when they have so few social, economic and political reasons in order to claim that humanity?” he asked. “So few political resources. So few economic, educational resources to articulate the humanity. How do they still claim, and be able to see something more than what the world says about them? I think it’s in that culture and it’s in the faith that is inseparable from that culture. That’s why I call the blues secular spirituals. They are a kind of resource, a cultural and mysterious resource that enables a people to express their humanity even though they don’t have many resources intellectually and otherwise to express it. Baldwin only finished high school. Wright only the ninth grade. But he still had his say. And B.B. King never got out of grade school. And Louis Armstrong hardly went to school at all. Now, I said to myself, if Louis could blow a trumpet like that, forget it, I’m gonna write theology the way Louis Armstrong blows that trumpet. I want to reach down for those resources that enable people to express themselves when the world says that you have nothing to say.

“People who resist create hope and love of humanity,” he said. “The civil rights was a mass movement, but a movement defined by love. You always have both sides. You have bad faith and good faith. I like to write about the good faith. I like to write about faith that resists. I like to write about faith that empowers. I like to write about faith that enables people to look another in the eye and tell ’em what you think. I remember growing up in Arkansas. There were a lot of masks. I wore a mask in Arkansas as a child, not in my own community but when I went down to the white people’s town. I knew what they could do to you. But I kept saying to myself, ‘One of these days I’m gonna say what I think to white people and make up for lost time,’ and so the last 40-something years that’s what I been doing. I write to encourage African-Americans to have that inner resource in order to have your say and to say it as clearly, as forcefully, and as truthfully as you can. Not all would be able to do that ’cause white people have a lot of power.

“Now white churches are empty Christ churches,” he said. “They ain’t the real thing. They just lovin’ each other. That’s all, that’s all that is: socializin’ with each other, that’s what they do most of the time. You seldom go to a church that has any diversity to it. Now how can that be Christian? God was in Christ reconciling the world unto God’s self. Well, it’s in white churches that God and Christ separated us from white people. That’s what they say. And I’m sayin’ as long as you are silent and say nothin’ about it, as Reinhold Niebuhr did, say nothin’, you are just as guilty as the one who hung him on the tree because you were silent just like Peter. Now if you are silent, you are guilty. If you are gonna worship somebody that was nailed to a tree, you must know that the life of a disciple of that person is not going to be easy. It will make you end up on that tree. And so in this sense, I just want to say that we have to take seriously the faith or else we will be the opposite of what it means.

“My momma and daddy did not have my opportunity, so when I write and speak, I try to write and speak for them,” he said. “They not here. They never had a chance to stand before white people and tell ’em what they think. I gotta do it somehow. I try to do that all over the world. I think of Lucy Cone and Charlie Cone, and of all the other Lucy Cones and Charlie Cones that’s out there who cannot speak. I think of them. I don’t think of myself, I think of them. It deepens my spirituality. It gives me something to hold on to, that I can feel and touch. It’s a very spiritual experience, because you are doin’ something for people you love who cannot and will never have a chance to speak in a context like this. So, why do I need to speak for myself? I need to speak for them. If you feel passion in my voice, you feel energy in this text, that’s because I was thinkin’ of Lucy and Charlie, my daddy, and my mama. And as long as I do that, I’ll stay on the right track.” (source: Turthdig -- © 2013 Truthdig, LLC. All rights reserved.)

Andrew Bryan, Founder of the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia

First African Baptist Church of Savannah, Georgia

From PBS's series Africans in America -- Andrew Bryan, the founder of the First African Baptist Church, was born enslaved in 1737, on a plantation outside of Charleston, South Carolina. He served as coachman and body servant to Jonathan Bryan, who along with his brother Hugh and several other planters, was arrested for preaching to slaves. Jonathan Bryan's plantation became the center of efforts by dissenting group of planters to evangelize their slaves.

In 1782, Andrew was converted by the preaching of George Liele, the first black Baptist in Georgia, who was licensed to preach to slaves along the Savannah River. Liele baptized Andrew and his wife Hannah. When Liele and hundreds of other blacks left with the British later that year, Andrew continued to preach to small groups outside of Savannah. With his master's encouragement, he built a shack for his small flock, which included a few whites. Although he brought hundreds into his church, 350 others could not be baptized because of their masters' opposition.

Andrew Bryan (1737 - 1812)

Fearing slave uprisings and desertions to the British, Georgian masters forbade their slaves to listen to Andrew's sermons. Even slaves who had passes were stopped and whipped, and members of the church, both slave and free, were harassed, whipped, and jailed. Jonathan Bryan and several other sympathetic planters protested Andrew's imprisonment. Upon his release he continued to preach in a barn on the Bryan plantation, between sunrise and sunset.

With the support of several prominent white men of Savannah who cited the positive effect of religion on slave discipline, Andrew was ordained and his church certified in 1788. When his own master died, Andrew Bryan purchased his freedom. In 1794, Bryan raised enough money to erect a church in Savannah, calling it the Bryan Street African Baptist Church -- the first black Baptist church in Georgia (and probably the United States), as well as the first Baptist church, black or white, in Savannah. By 1800, the church had grown to about 700; they reorganized as the First Baptist Church of Savannah, and 250 members were dismissed in order to establish a branch outside of Savannah.

Bryan died in 1812, having obtained a house of his own, property in Savannah and in the country, and the freedom of his wife -- though his "only daughter and child, who is married to a free man" remained in slavery along with her seven children, since according to law children inherited the condition of their enslaved mothers. (source: PBS)

Remarkably, a few black preachers in the South succeeded in establishing independent black churches. In the 1780s, a slave named Andrew Bryan preached to a small group of slaves in Savannah, Ga. White citizens had Bryan arrested and whipped. Despite persecution and harassment, the church grew, and by 1790 it became the First African Baptist Church of Savannah. In time, a Second and a Third African Church were formed, also led by black pastors. (source: PBS)

Thursday, March 28, 2013

The Chinese in Mississippi: An Ethnic People in a Biracial Society

The Chinese first arrived during the Reconstruction period (1865-1877). The period was a time of considerable turmoil in Mississippi as the state adjusted after the Civil War to the end of slavery and the defeat of the Confederacy. Tensions were high between the black freedmen and whites. Because the labor system was unsettled, planters recruited the Chinese as a possible replacement for the freed African American laborers. The United States census of 1880 listed 51 Chinese in Mississippi, mostly in Washington County.

Like most Chinese immigrants to the United States, those coming to Mississippi were mainly from the Sze Yap, a district in south China. Sze Yap was a more commercially sophisticated area than many parts of China at the time, with a history of contacts with foreign traders. Immigrants were likely from peasant and artisan families. Traditionally, young males from the area traveled far for work to supplement the family income. The initial immigrants to Mississippi came not to settle here, but to earn money to send home as savings to be used when they returned to China. Once they were here, though, others soon arrived, often with more financial resources than the first immigrants. Few women came in this period and the men remained socially isolated. Furthermore, the state’s preoccupation with racial issues resulted in the Chinese being classified as non-white in a predominantly biracial Mississippi social system. These early immigrants to the state sought, however, economic success rather than social recognition, since they did not intend to stay long.

Joe Gow Nue Grocery Store, Greenville, Mississippi

Grocery stores

The Chinese soon realized that working on a plantation did not produce economic success. They then turned to another activity — opening and running grocery stores. The first Chinese grocery store in Mississippi likely appeared in the early 1870s. Tax records in the early 1880s list Chinese as landowners in Rosedale, in Boliver County.

Wong On, a prominent early Chinese settler in the Delta, illustrates the way immigrants became merchants. He had been born near Canton, China, in 1844. He emigrated to California in 1860, worked on the transcontinental railroad, and then came south for another railroad job.

Little is known of Wong On’s early days in Mississippi, but he probably picked cotton, became a tenant farmer on a plantation near Leland, married a black woman, and opened a store in Stoneville. His first grocery was probably like those of other Chinese groceries in this period — small, one-room shacks which carried only a few basics, such as meat, corn meal, and molasses. The people who shopped at his store were mostly poor blacks working on plantations, relatively well-off laborers who had cash from their work draining swamps and cutting timber in the Delta in the late 19th century, or poorly paid manual laborers in town.

In those days, stores were not self-service and customers had to ask for what they wanted. Merely buying a sack of corn meal was a complicated matter — the Chinese storeowners at first did not speak English and their customers did not know Chinese. Thus, pointing at merchandise was how transactions were handled. Other businessmen sometimes took advantage of the Chinese, and their lack of understanding English and the Southern legal system left them vulnerable to exploitation. At best, storeowners were dependent on customers with few economic resources themselves.

Chinese grocers, nonetheless, carved out a successful, distinctive role. One reason for their success was a cohesive family system. After they established their small businesses, these early Chinese merchants would send back home for a young male from their family to come and help the business succeed and to learn how to run a business. That young relative would later perhaps use his savings, loans from relatives, and credit from wholesale suppliers to set up his own grocery. Hard work, experience in business operations, and a reputation for financial integrity soon led to good credit ratings for the Chinese merchants. For generations, grocery stores would be passed down from father to son, and as late as the 1970s, six family names accounted for 80 percent of the Delta Chinese population.

Triethnic society

Chinese in the Delta attempted to maintain a certain distance from others in society, hoping to insulate themselves from problems and concentrate on their economic success. They experienced considerable distance from Delta whites through their exclusion from social organizations, country clubs, fraternal groups, recreational activities, and most importantly, white public schools. Several Delta cities maintained not only separate schools for blacks and whites, but also small classes for Chinese students as well. In the mid-1940s, Cleveland, for example, had two classrooms for Chinese students, enrolling thirty-six students who were taught by three teachers, including one Chinese. The Chinese worked over the years to affiliate with the white community as much as possible because whites held the highest social status in the Jim Crow South. Naming patterns came to reflect this change. Chinese parents might pick first names for their children like “Coleman” and “Patricia” to suggest identification with whites.

Mississippi Chinese society

The desire to become identified with white society shaped the institutions that anchored Chinese society in Mississippi. The “tong” was a social organization that structured much Delta Chinese social activity in the early days of settlement. But by the 1930s, the Baptist church became important for the Delta Chinese, particularly the Chinese Baptist Church in Cleveland, and served as a center for wedding banquets, community service projects, fundraising activities, funerals, and other occasions that brought the extended Chinese community together. The mission school attached to the church provided education for the Chinese, preparing them for identification with white society. In addition, the Chinese community in the mid-20th century sponsored dances for college and high school students, held summer schools, and promoted social clubs. The Chinese in towns like Greenville kept Chinese cemeteries separate from those of whites and blacks. Typically the cemeteries had small, well-tended plots with high fences around them.

Assimilation

By the post-World War II years, the Chinese in Mississippi were consciously seeking acculturation into American society, within a Southern regional context. Their numbers, however, remained small and their settlement was concentrated in the Delta. Fourteen Delta counties accounted for over ninety percent of the Mississippi Chinese population in 1960. The Delta had a larger Chinese concentration than any other area of the South. At this time though, acculturation was not complete. One college coed in this era complained, for example, that, despite being Mississippi born and bred, her white friends called her the Delta lotus, evoking an image of an Asian flower. “I’m a Delta Southerner,” she said, “but still a lotus and not a magnolia.”

Since the 1960s the Chinese in Mississippi have faced the decline of their economic base as distinctive Delta groceries serving a black clientele. Blacks now have more choices of grocery stores, including large chain stores. Children of Chinese families often go away to school now and often do not seek to inherit and run old businesses. Chinese cluster more than ever in towns and move to nearby mid-south cities, such as Jackson or Memphis. The Chinese who remain, and newcomers who still arrive seeking economic opportunity, run Chinese restaurants, which may serve barbecue as well as Cantonese fare. Families often grow their gardens to have traditional Chinese cuisine at home, using fresh bok choy, bitter melon, mustard, or other ingredients of Chinese cooking. Families celebrate traditional Chinese holidays, out of sight of most Mississippians, to honor their ancestors.

Conclusion

The Delta was settled by other ethnic groups as well as the Chinese. Lebanese, Syrians, Jews, Mexicans, and Italians were all notable for their roles there, but the Chinese had perhaps the most challenging adjustment because they came from a culture that seemed unusual to most other Mississippians.

Moreover, the Chinese sought economic opportunities in Mississippi at a time that seemed unlikely to bring them success, but they filled a distinctive economic role as merchants. They won the friendship of the blacks they served and the whites who came to trust their honesty in business dealings. They were small in number and never had the support for ethnic identity that large Chinese communities in America had, such as access to Chinese genealogical organizations, Chinese literature and media, Chinese theaters or markets, or Buddhist temples.

Still, the Chinese made new lives as Southerners and became a notable feature of Delta society. In 1960, the United States Census listed 1,244 Chinese in Mississippi and reported that the Delta had more Chinese than any other part of the South. By 1970 the Chinese population in the state had grown to 1,441. The 2000 Census reported 3,099 Chinese lived in Mississippi, out of an Asian population of 18,626 in the state. (source: Mississippi History Now -- Charles Reagan Wilson, Ph.D., is director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and professor of history and Southern studies at the University of Mississippi. )

Anti-Chinese Laws and Racist Mobs

Anti-Chinese Laws and Racist Mobs

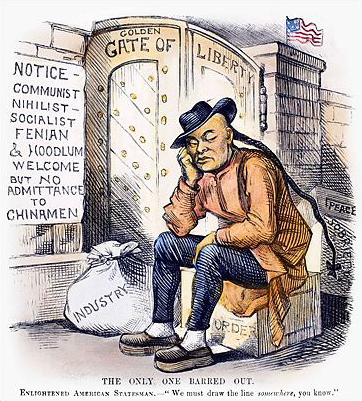

As reported in the Revolutionary Worker -- The Chinese immigrants who came looking for the "Golden Mountain" did the hardest, most dangerous and lowest paid labor. They were denied the most basic rights and subjected to racist violence and terror. In 1858, 140 years before California's anti-immigration Prop 187, the state passed an immigration law excluding Chinese from entering the state. And in 1862 a "White Labor Protection Act was passed.

The constitution of California was rewritten in 1879 forbidding any man or woman of "Chinese or Mongolian" ancestry from earning a living by working for a white man. And the legislature delegated "all necessary power" to towns and cities "for the removal of Chinese." The state constitution declared that the Chinese people were "dangerous to the well-being of the State."

In 1882 the Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, which decreed that a Chinese man who worked with his "hands," who was a "manual" laborer, would be prohibited from coming to America. And the people from China who were already residents were barred from becoming citizens. Chinese, like Black people and Indians, were not allowed to testify against whites in court. They were barred from public schools and forbidden to own real estate or get business licenses or government contracts. In San Francisco, laws were passed against the Chinese like a "queue tax," a "cubic air ordinance" requiring that every residence have so many cubic feet of air per inhabitant, and a "pole law" prohibiting the use of carrying baskets on poles. Laws that specifically targeted Chinese immigration stayed on the books until 1965. The Chinese Exclusion Act was not repealed until 1943--and even then immigration of Chinese was given a quota of only 105 per year!

The white labor movement in California became a major force behind the racist campaigns to drive the Chinese out. Mobs stormed through towns where Chinese immigrants lived, burning homes and looting shops. Chinese were lynched and scalped. They had their pigtails cut off and were branded with hot irons. In one incident a mob caught a Chinese miner and sliced off his genitals. In one Nevada town a Chinese laundryman was tied to a wagonwheel and the buckboard was driven at high speed through the town until the man's head fell off. One Chinese crab fisherman who was beaten to death was branded by hot irons, his ears sliced in half with a knife and his tongue cut off.

On a single night in Los Angeles in 1871, 20 innocent Chinese men were lynched or burned alive by mobs of white men. Four men were crucified spread-eagle and then executed with knife and gun.

And in 1885, in Rock Springs, Wyoming, 28 Chinese men were murdered by local townspeople. In an orgy of bloodletting, mobs not only burned the Chinese alive but then mutilated their dead bodies.

The racist treatment of Chinese immigrants in California in the late 1800s was very connected with the oppression of Black people in the South. The anti-Chinese measures during this period were passed in Congress by a combination of Southern and Western votes. Southern plantation owners and politicians would not tolerate a policy in California that might have unsettling consequences in the South. And the more California became committed to a Jim Crow policy in relation to the Chinese, the greater was its obligation to support Southern racist policies in Congress.

After the Civil War, Southern plantation owners--who were worried that freed slaves would be "unmanageable"--considered substituting Chinese coolie labor for Black labor. Southern plantation owners visited California with this in mind. And during the 1870s, Chinese workers were imported to states like Louisiana and Mississippi and pitted against Black workers. A southern governor explained: "Undoubtedly the underlying motive for this effort to bring in Chinese laborers was to punish the negro for having abandoned the control of his old master, and to regulate the conditions of his employment and the scale of wages to be paid him."

Eventually, plantation owners in the South stopped importing Chinese labor as the system of sharecropping became established. But Chinese laborers continued to be used in other parts of the world to replace Black slaves. From 1845 to 1877 a great movement of Chinese coolie labor from China was a direct consequence of the end of slavery in the British Empire. In colonies in the Caribbean and Latin America Chinese coolie labor was used to replace Black slave labor. Over 40,000 Chinese coolies were imported to Cuba alone--of whom it has been said that at least 80 percent were decoyed or kidnaped.

Driven Off the Land

By the beginning of the 1890s an economic depression hit the U.S. and Chinese immigrants were subjected to a whole new level of attack. There is a striking and ugly parallel between this period and the atmosphere of terror directed against Mexican and Latin American immigrants in California today.

The people who had built the railroads and levees were painted as a plague on society. White workers who were losing their jobs were told that the problem was Chinese immigrants. In 1893 the Los Angeles Times wrote: "White men and women who desire to earn a living have for some time been entering into quiet protest against vineyardists and packers employing Chinese in preference to whites." A wave of racist anti-Chinese riots broke out in the Central Valley. Takaki writes that "From Ukiah to the Napa Valley, to Fresno to Redlands, Chinese were beaten and shot by white workers and often loaded into trains and shipped out of town." These violent attacks on Chinese immigrants were concentrated in the Sacramento and San Joaquín River valleys, and especially where they join at the Delta (see map). Chinese immigrants bitterly remembered this violence and expulsion as the "driving out." While a handful of Chinese towns remained in the Delta, the vast majority of Chinese immigrants were driven from the land and forced into marginal survival. For the most part, they were denied any opportunity for work except menial jobs like washing clothes and cooking.

The levees built by Chinese immigrants created huge profits for capitalists and opened up some of the most fertile and productive land in the world. In return, these immigrants were denied the most basic rights. Their communities were burned. Dozens were murdered by racist mobs. And they were forced from the very land they had created from the Delta swamps. (source: Revolutionary Worker)

The Mississippi Delta Chinese Experience

From MBB News, "Magnolias and Chopsticks: The Mississippi Delta Chinese Experience Part 1," by Sandra Knispel, on 21 September 2011 -- The Chinese of the Mississippi Delta are an often-overlooked part of the history of the Deep South. In part one of our two-part series, MPB’s Sandra Knispel tells the story of what made them come all the way to the small towns of the Delta.

China is a long way from the United States. Yet many made the voyage, hoping for a better life. In the late 1860s, the first Chinese reached the Mississippi Delta. According to data collected by the University of Mississippi's Center for Population Studies, in 1870 only 16 Chinese lived in the Magnolia state.

“The Chinese were attracted to the Delta by plantation owners who were looking for cheap labor to replace many of the slaves who were no longer working on the plantations.”

John Jung is a California State University professor emeritus of psychology and author of Chopsticks in the Land of Cotton and Southern Fried Rice, which both describe the Chinese experience in the Deep South. The plantation owner’s plans failed quickly when the new immigrants left sharecropping pretty much immediately.

Sot Dr. John Jung: That’s partly because the Chinese were able to find a more lucrative way of earning a living.” 6

That lucrative way came as small-scale grocers. Chinese immigration to the Deep South really began to pick up in the early 20th century. Luck Wing is a retired Delta pharmacist whose parents left China in the 1920s.

“For a better life, you know. The Chinese word for the United States back then was Gam Saan, that’s the Cantonese for “Gold Mountain.”

“The Chinese at home in China would literally think that all you needed to do was to come to the United States and work somewhat and you can share in the wealth,” says Frieda Quon.

Frieda Quon, a retired librarian at Delta State is like Wing is a second-generation Chinese-American. Both were born and raised in the Mississippi Delta.

“My father came at the age of 14 from a small village in China, Canton. And he came to Chicago to join his older brother who was already there in a laundry business."

Quon’s father came to the U.S. in the 1920s, originally on forged papers, pretending to be someone else’s child.

"So, when dad left, he was the youngest to come, he wouldn’t get to see his parents again. His father died, never saw his father again. He did get to see his mother but it would be years later.”

At some point in the late 1930s, her father moved 600 miles south, down from Illinois to the Magnolia state.

"My uncle heard about Mississippi and the better opportunities for [making] a living in Mississippi," Quon explains. So, he left my father, probably with a cousin or uncle or others, to run the laundry while he journeyed to Mississippi to investigate. So, yes, this was better than the laundry and so then eventually my father came to Mississippi as well.”

In the Delta, nearly all Chinese were small grocery owners, filling a void left by white plantation owners who had stopped the commissary business of selling goods to their black sharecroppers, often at rather unfavorable terms. Quon’s dad, too, had by now become a Delta grocer. But there was something else he wanted…

“In ‘39 or 1940, he went back to China to be married. And the custom then was to have a matchmaker. It was just willingly accepted. You know, my mom never saw dad before she married him. I think maybe they stayed for a brief time but then eventually both came on a ship and came to Mississippi.”

Unlike in the large urban centers of New York and Chicago where the immigrants lived in so-called Chinatowns, the Delta Chinese were largely on their own. Without a sizeable Chinese community around them, they ended up largely isolated in Mississippi’s rigid society.

“We were not with the white group and we were not with the black group. And so, I guess, we were somewhere in the middle.”

They quickly learned that in order to survive one had to tread carefully and keep mum. Public neutrality in the emerging civil rights struggle of the 1950 and 60s became second nature to most Delta Chinese. At some point, Frieda Quon’s family even owned two groceries in Greenville:

"The way the stores were arranged -- they were diagonally. One on Alexander and Eureka and actually the other one was on Alexander and Eureka. But one focused more on the trade for the black customers, and then the other one for the white customers. Two separate stores.”

The grocery stores proved to be the ticket to survival in the Deep South. And even today, scattered among the many shuttered business facades of the Delta, here and there are still some small surviving Chinese groceries… long past their heyday, often with old, sun-bleached neon signs, but nevertheless part of the Delta’s storied history. [source: MBB News--Sandra Knispel, MPB News.]

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction

As reviewed in the New York Times Sunday Book Review, "Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction, By Eric Foner," reviewed by James Goodman, on 29 January 2006 --ERIC FONER wrote "Forever Free" to combat what he calls our "sheer ignorance" of the 15 years between the Emancipation Proclamation and the withdrawal of the last federal troops from the South in 1877. Yet when it comes to those years, ignorance is progress, a step in the right direction.

What could be worse than ignorance?

Horrible history: the distortions, misinformation and myths that passed for "the facts of Reconstruction" for nearly a century after 1877. In that history, Lincoln's magnanimous plan for reunion died with him, as power-hungry, South-hating Radical Republicans in Congress rolled over Andrew Johnson and set out to punish the South for the war.

What followed was a "tragic era" of military occupation, corrupt state governments, heavy taxation, wasteful spending and, worst of all, "Negro rule": the enfranchising of ignorant, gullible, bestial black men. All seemed lost, until the Ku Klux Klan arose and expelled the carpetbaggers, dragged the scalawags back to the white side of the color line and put the former slaves in their place. Home rule was restored, the South redeemed.

That's not a caricature. That was Reconstruction at our finest universities (nowhere more than at Columbia, where Foner now holds an endowed chair) and it was Reconstruction in popular novels, histories and films, most notably D. W. Griffith's repugnant classic, "The Birth of a Nation." Woodrow Wilson, a political scientist and Princeton professor before he became president, viewed the film in the White House. It is "like writing history with lightning," he said, "and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true."

It was terrible, but not true - as African-Americans knew. "One fact and one alone explains the attitude of most recent writers toward Reconstruction," W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in a blistering critique in 1935: "they cannot conceive Negroes as men." Du Bois saw Reconstruction as a noble effort to establish genuine democracy in the South. His white contemporaries ignored him, but a generation later his sources and insights contributed mightily to a new history, a history that has been elaborated and refined but remains the standard one today.

"Forever Free" will not supersede "Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877," the grand synthesis Foner published in 1988. His new book is aimed at readers basically unfamiliar with American history. For their benefit, he opens with a short account of slavery and emancipation. He then turns to the struggle to determine the meaning of freedom and the character of American democracy after the war. "The vast economic and political power of the South's white elite hung in the balance," he writes. So did the "lives and dreams" of four million former slaves.

Landowners and merchants wanted laborers to plant and pick their cotton - on terms as close to those of slavery as they could get. Freedmen and women wanted land of their own. They also wanted schools, churches, equality before the law and the franchise. They didn't get land. But by the early 1870's, they had achieved a measure of economic autonomy, and the legal and political tools - especially the Civil Rights Acts and the 14th and 15th Amendments - necessary to protect it. Black men voted, served on juries and held local, state and national office. "For a brief moment, the country experimented with genuine interracial democracy," Foner writes. But it wasn't easy or pretty, and it provoked a ferocious reaction. In the face of fraud and terror, the freedmen's white allies, north and south, abandoned them.

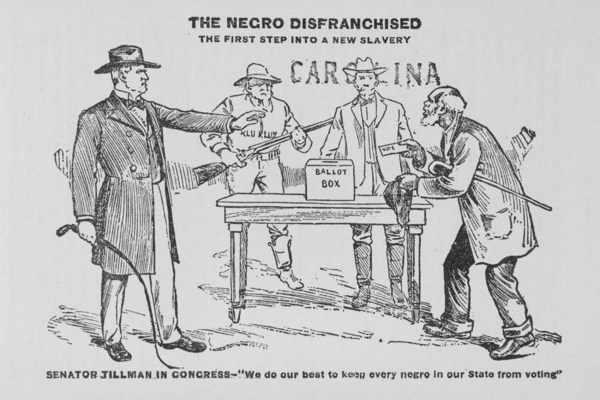

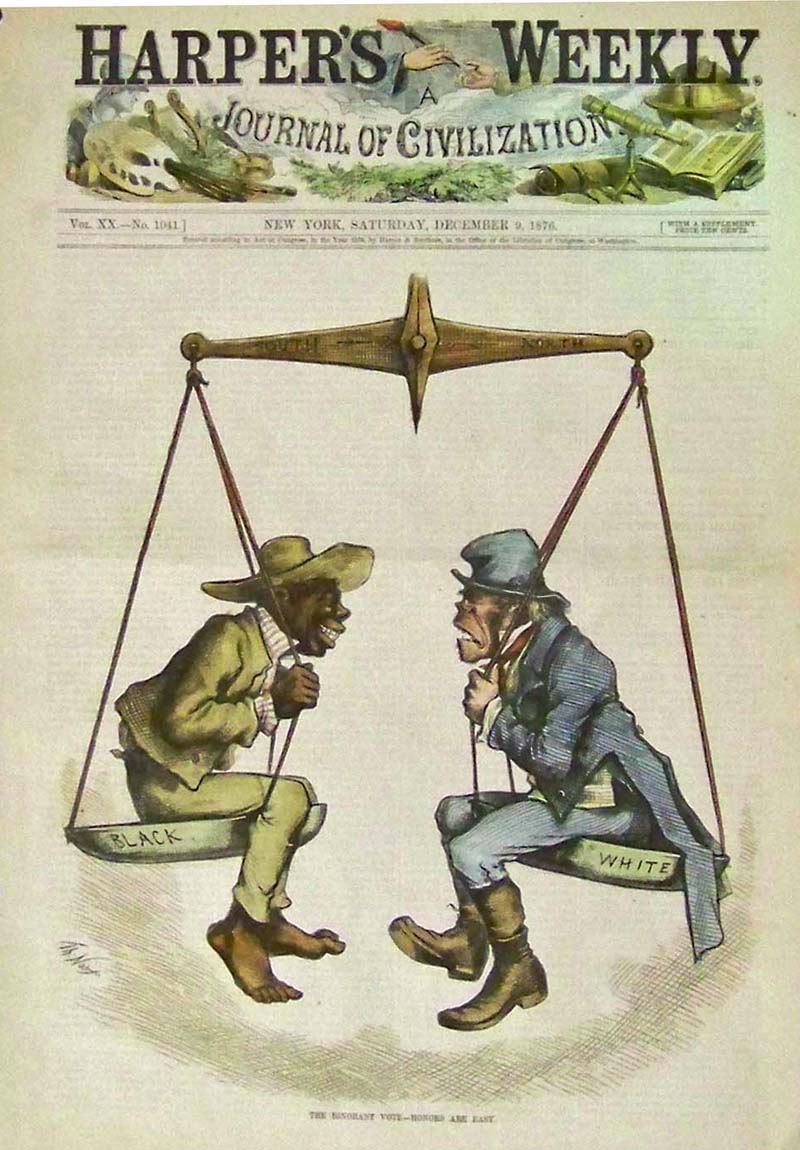

In his last two chapters, with the uninitiated again in mind, Foner traces the lines of race and politics that run from Reconstruction to the age of segregation to the civil rights movement to our own time. And throughout, the history lesson is enhanced by Foner's collaboration with Joshua Brown, a social historian and cartoonist. Brown selected the book's "illustrations" (scores of drawings, engravings, paintings, photographs and cartoons), and he wrote six short "visual essays." Those essays, set among Foner's chapters, vividly show how images - a Republican buying one black man's vote, Klansmen lynching another - are never merely illustrations of historical experience. They are another dimension of that experience.

"Forever Free" is a good book: passionate, lucid, concise without being light. But will it be a match for ignorance? The old history took hold when Northerners concluded that the freedmen and women were as hopeless as white Southerners said they were; their fate was best left in white Southern hands. Through decades of lynching, segregation, disfranchisement, debt peonage, heightened prejudice and abject poverty, history justified inaction by demonstrating that federal interference only made race matters worse.

The new history took hold in the 1960's, during the civil rights movement and Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society," when many Americans came to believe that the government had an obligation to join the struggle for equality, and that they had a huge stake in the outcome of that struggle.

Four decades and untold political abuse later, our federal government is again held in low esteem. Many wonder if it is even competent to do what it used to do best: wage war. I would like to think that the prejudice at the heart of the old history of Reconstruction would prevent its revival. But as long as Americans continue to see government simply as a problem, we won't know much, or care, about Reconstruction. [source: The New York Times -- James Goodman, a professor of history at Rutgers University, Newark, is the author of "Stories of Scottsboro" and "Blackout."]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)