From H-Net, "Mobilizing Power from the Top Down," by Kelly D. McMichael, on August 2004 -- Most historians view the hegemony of the Democratic Party and the disfranchisement of African Americans in the late-nineteenth-century South as inevitable, but Kent Redding argues in Making Race, Making Power that the path state politics might have taken was entirely unpredictable. Redding's easily readable text makes a convincing argument for the need to approach southern politics from a different direction, looking at southern elites not just from their exalted positions or their ability to command resources (as power holders) but as power makers. Redding is interested in the process elites used to collectively mobilize power and examines one state, North Carolina, to determine how the political mobilization process led to disfranchisement. North Carolina shared many similarities with other southern states during the period. For example, Republicans were ousted from power in the 1870s, the Ku Klux Klan intimidated large numbers of African Americans, and blacks and many poor whites lost the vote due to the poll tax, literacy, and registration requirements. But North Carolina was exceptional because it suffered less than many of the other southern states from political violence, corruption, and fraud, leaving the democratic processes in the state relatively intact well into the 1890s. Black political mobilization remained strong, and a fusion between the Republicans and Populists in 1892 allowed the two parties to defeat the Democrats. The loss led to the extraordinary white supremacy campaigns of the rest of the decade.

Kent Redding. Making Race, Making Power: North Carolina's Road to Disfranchisement.

Redding begins by posing several questions, including asking why it took so long for African Americans to be disfranchised (when Democrats were already in power) and why blacks were allowed to vote until the 1890s in such large numbers. Essentially, he wants to know why disfranchisement occurred when it did. Why did Democrats formally restrict suffrage when they did? Redding determines that white Democratic elites in North Carolina, and likely elsewhere in the region, were initially divided about what political strategies the party should pursue. Over time the party had to face the powerful and innovative techniques of their competition. Organized blacks and Populists created new means of political mobilization that challenged the old patterns of organization and forced the Democrats to work along new lines, mainly by adapting the same types of strategies their opponents employed. The Democrats combined the use of new political techniques with their already solidified social position and abundant resources, a combination that allowed the party to gain a solid hold on the state and thwart any second or third party competition.

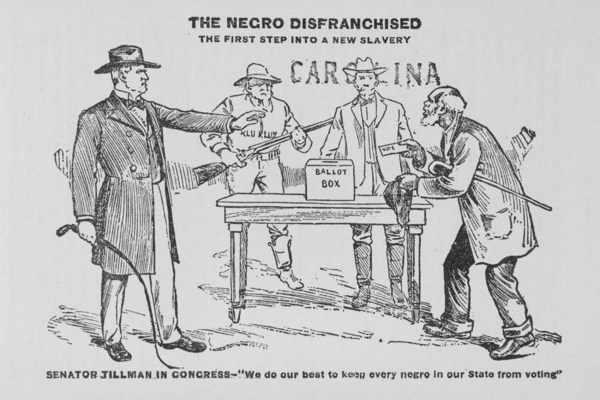

"The Negro Disfranchised. The First Step Into A New Slavery. Senator Tillman in Congress - 'We o or best to keep every negro in our State from voting."

Redding begins his analysis by examining voter turnout patterns across thirty years in the eleven traditionally southern states. Using multiple variable-centered analyses, he quantitatively reveals the loose process by which voter turnout was determined, a process combining race, competition, voting regulations, and class. Overall voting turnout declined from 65 percent in 1880 to less than 30 percent by 1912. The low turnout proved a necessary condition for Democrats to create an elite, racially based one-party system. The state no longer needed to mediate between contending interest groups when a large proportion of the voters no longer participated. Instead the party--and by default the state--could work at eliminating those people from the voting rolls permanently.

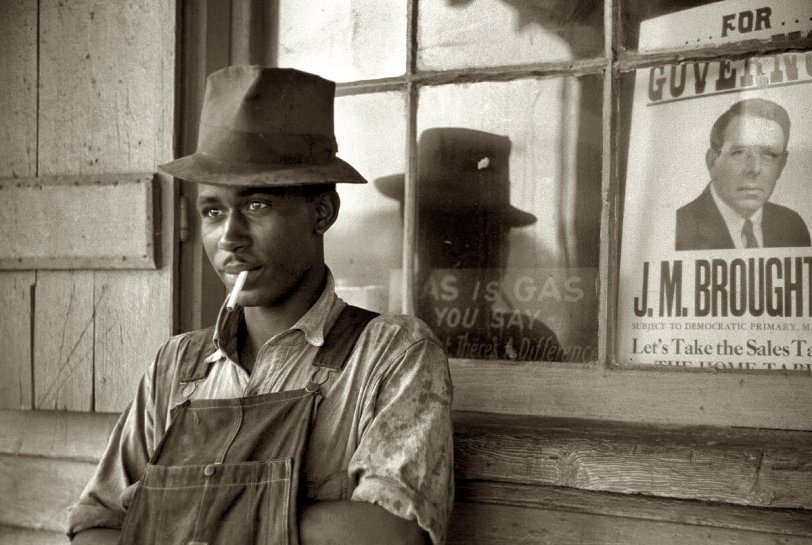

After examining the declining voter turnout in the South and illustrating the multiple factors responsible, Redding concentrates on the case of disfranchisement in North Carolina. He argues that the state Democratic party was vertically organized, a term that denotes power based on hierarchies within the group. In the case of elite whites, the power reflects a local, community-based system of patronage and kinship, controlled by key county offices. While politicians spouted racially based rhetoric early on, such policies were loosely and inconsistently applied. Race simply did not prove a strong organizing factor for the Democratic party in the state until the late 1890s. Local elite rule proved strong enough over two decades to make disfranchisement unnecessary, but continued high voter turnout through the 1880s stressed elite whites, and the Democrats found that they could not predict or control the strong mobilization being mounted by blacks and populists, a condition that eventually made disfranchisement necessary.

While Democrats used a vertical organization of power, blacks in the Republican and Populist parties experimented with and succeeded in creating a horizontal form of power, creating new types of party mobilization based on an identity determined by interest. Republicans coalesced a party around issues of race while Populists did the same using the economic interests of farmers. Democrats still engaged in the traditional method of creating a party--building support through local networks--but found that identity based issues superseded local elites' abilities to control the voting population.

Faced with a resounding defeat in 1892 by the fused Republicans/Populists, the Democratic party in North Carolina knew it had to radically change its party organization. The party seized the political innovations of their competitors and recaptured the state by making the Democratic party synonymous with racial purity. Not only did the Democrats create a party based on white supremacy, they linked the issue of manhood (gender identity) with whiteness and confirmed the loosely held notion that all whites held a common identity based purely on their skin color. Potential white political fusion with blacks based on economic issues was effectively ended; whites were symbolically separated from blacks as each race was given a specific identity. Once back in power, Democrats used their control to eliminate their competition permanently.

Although Redding is a sociologist, his work is thoroughly grounded in the historiography of disfranchisement. It adds greatly to the standard in the field, J. Morgan Kousser's monograph, The Shaping of Southern Politics, by giving detailed evidence of the depth of African American political activity well into the 1890s. The Republican Party remained viable far longer than many historians suspect and blacks formed its vibrant backbone. Redding's evidence takes some of Michael Perman's interpretations in Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908 to task. Perman asserts that the Democratic elite were consumed by racism and that their political agenda was driven by the need to end biracial democracy in the South. Redding's work acknowledges the part that white supremacy played in disfranchisement, but his interpretations shine in their nuanced analysis of the multiple factors leading to a one-party state. Redding argues that race alone was not the overwhelming cause of disfranchisement. How could it be when held up against his original question of why the Democrats waited so many years to eliminate black suffrage? Race was only one factor among many others--and not even the most important factor--that determined the eventual disfranchisement of a significant number of voters.

Redding's effort to illustrate the fluid and relational means with which race, class, and even gender were all factors in determining disfranchisement is excellent. His work is extremely readable, despite the large amount of quantitative data included. His use of cliometric analysis, archival, and secondary sources brings authority to his conclusions. Redding presents a highly convincing argument, illustrating how Democratic elites became mobilizers of power. Race did not determine party policy, Redding argues, rather political battles determined the stand elites took on race. Redding proves that the solid democratic South was not a monolith, but rather that politics in the South remained dynamic well into the early 1900s and that marginal groups could exert real power that forced majorities to create or utilize new collective actions to maintain or regain control. (source:H-Net, )

Good day! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was

ReplyDeletewondering if you knew where I could get a captcha plugin for my comment form?

I'm using the same blog platform as yours and I'm having

trouble finding one? Thanks a lot!

my web page :: trading commodity

Hi i am kavin, its my first time to commenting anywhere, when i read this piece of writing i thought i could also create comment

ReplyDeletedue to this good post.

My page ... building muscle