From the Fall 2010 National Park Conservation Association Magazine, "Freedom’s Fortress At Virginia’s Fort Monroe, preserving the past may mean striking out in a new direction," by Jeff Rennicke -- Hushed voices. The slow slap of waves. The creak of an oar lock. It is May 23, 1861. Three figures, half-hidden by a cloak of darkness, set off from Sewell’s Point near Norfolk, Virginia, to row a small boat across the wind-stirred waters of Hampton Roads to Old Point Comfort at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

It is a simple act, yet one that will change the course of American history, spell the beginning of the end for slavery, and, 140 years later, sit squarely at the center of efforts to preserve an American landmark and create the newest unit of our National Park System. On this night, however, the three men simply take their bearings, lean hard into the oars, and row.

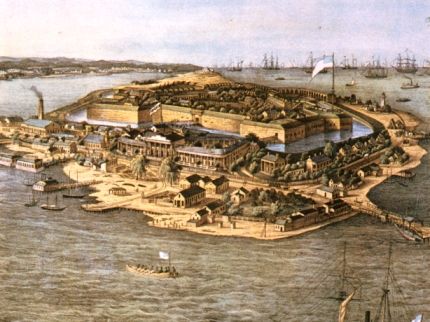

Jutting into the deep waters of Chesapeake Bay off Virginia’s eastern coast, Old Point Comfort is a natural lookout, a clenched fist protecting one of the largest natural harbors on the Eastern Seaboard. Archaeological evidence shows that humans used the point as a transportation route and hunted migrating waterfowl and sea life for more than 10,000 years before Europeans arrived. In 1608, Captain John Smith dubbed Old Point Comfort a place “fit for a castle.” Yet forts, not castles, would play the leading role in the history of the Point.

As early as 1609, the British built Algernoune Fort—a wooden structure “10 hands high” and large enough to hold 40 soldiers and seven mounted cannons. Fire claimed the fort three years later. In 1619, the first African slaves to set foot on North American soil stopped here aboard Dutch ships bound for Jamestown. In 1727, the more formidable Fort George was built to guard against French invasion. Constructed of brick and shell lime, this was a fort “no ship could pass … without running great risk,” as Governor William Gooch would write in 1736. It was no match, however, for the hurricane that destroyed it in 1749.

During the War of 1812, the fledgling United States was dealt a stinging reminder of the point’s strategic importance. The single lighthouse that guarded Old Point Comfort at the time was no deterrent to the British Navy, which moved uncontested up the waterways to strike deep into the heart of the new nation, sacking Baltimore and setting fire to Washington. The lesson was not lost on President James Madison. In 1819, he appointed French military engineer Simon Bernard to oversee construction of the largest moat-encircled stone fort ever built in America. And he ordered it built at Old Point Comfort.

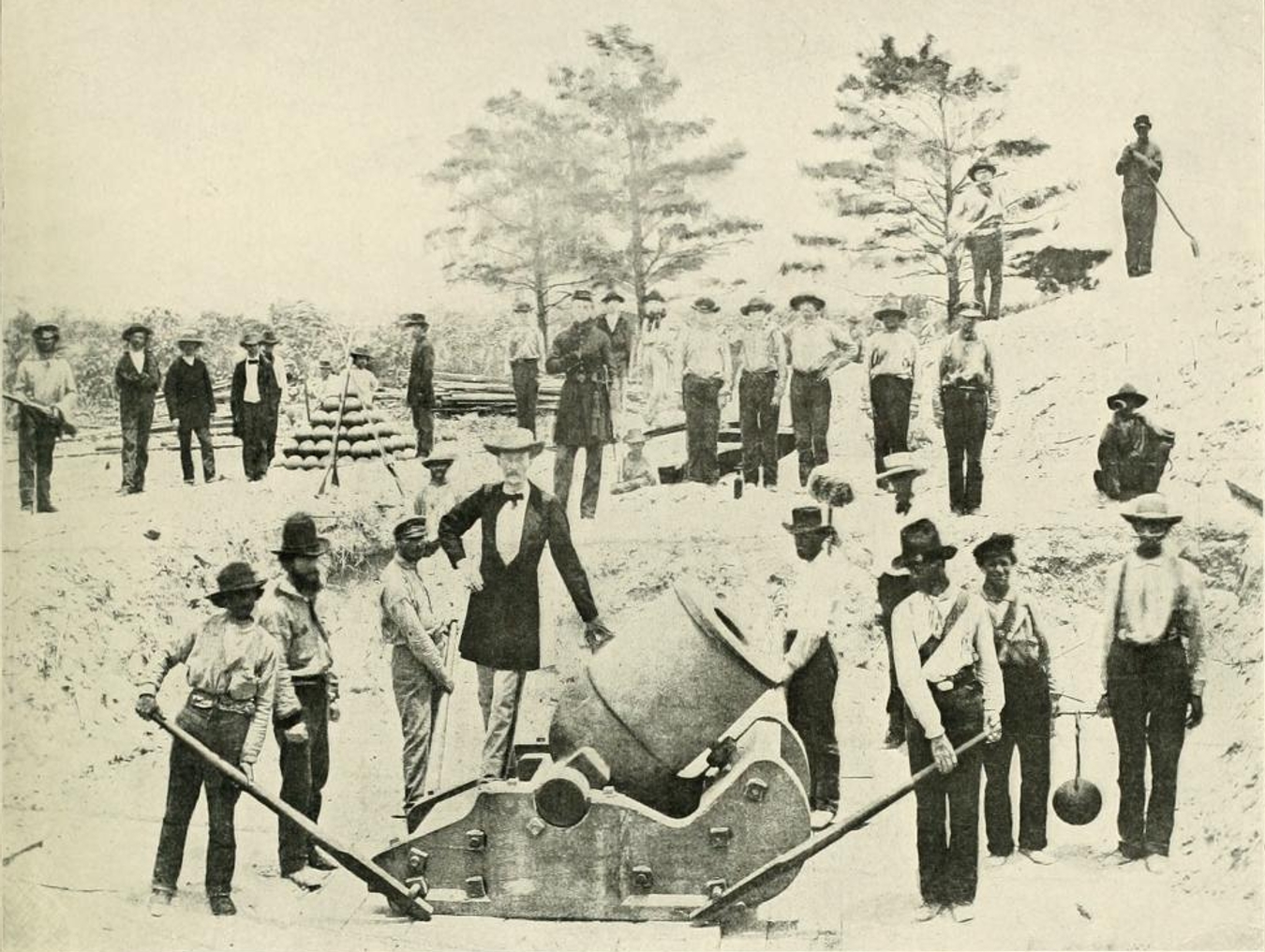

Fifteen years in the making and sporting a price tag of nearly $2 million, Fort Monroe is a true fortress—63 acres encompassed by a mile-long moat and fortified with granite walls 10 feet thick. It holds 380 gun mounts and housed 2,600 men in times of war. Named for our fifth president, it was considered nearly impregnable by land or sea, secure enough to house Abraham Lincoln during the height of the Civil War. Its labyrinth of streets and buildings have seen a parade of famous figures and events—Robert E. Lee helped with construction of the moat; Edgar Allen Poe, who enlisted under the alias of “Edgar A. Perry,” set his famous poem “Annabel Lee” at this “kingdom by the sea”; Chief Blackhawk and Jefferson Davis were both prisoners within its walls; Harriet Tubman acted as a matron of the fort’s hospital; soldiers atop the walls of the fort witnessed the March 9, 1862, battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac (a.k.a. CSS Virginia), which would change naval history forever.

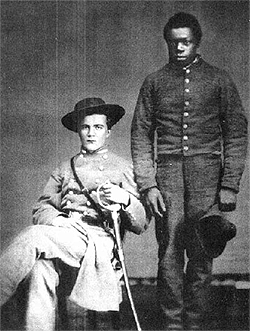

Yet for all of that, perhaps the fort’s greatest moment came that May night in 1861 when Frank Baker, Sheppard Mallory, and James Townsend—slaves belonging to Confederate General Charles Mallory—slipped a small, stolen boat into the waters of Hampton Roads and rowed for freedom.

What these three men did was an act of exceptional courage,” says Professor Robert Engs, author of Freedom’s First Generation. “Under the Fugitive Slave Act, there were dire consequences for runaway slaves.” Yet, if they did nothing, the men faced being ripped from their homes and families and taken south as part of the Confederate work force. And so they rowed for Fort Monroe hoping to find freedom, and according to Engs, became “the foot soldiers of a revolution that changed the course of U.S. history.”

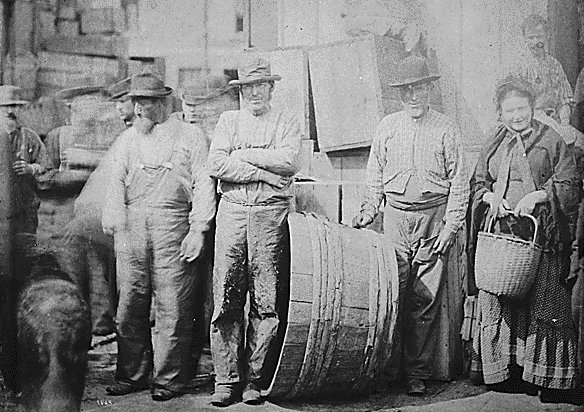

At Fort Monroe, Union General Benjamin Butler deemed the men “contraband of war” and refused to send them back to their owner. The next day, eight more slaves showed up at the fort; 47 the day after that. The three men had touched off the first mass freedom movement of the Civil War. Eventually some 20,000 men, women, and children flocked to the fort, an act that weakened the Confederate labor force, changed the focus of the war into a fight over slavery, and led directly to the Emancipation Proclamation and the disintegration of the institution. “Fort Monroe,” says Professor Engs, “is where freedom for all Americans truly began.”

Echoes of History

Still an active military installation, Fort Monroe has seen its role gradually change from one of coastal defense to headquarters for a series of Army commands including, most recently, the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command. But budget cuts and fort closures across the country had put the future of the fort in question. Finally, in 2005, the Department of Defense announced that on September 14, 2011, after 188 years of continual presence, the U.S. Army will vacate historic Fort Monroe. The move has touched off yet another battle in its long and storied history: the battle for the future of what has become known as “Freedom’s Fortress.”

The city of Hampton, where the fort resides, fired the first volley in that battle with its “draft reuse plan” released in 2006. Faced with an estimated 7-percent drop in tax revenue from the closure of the fort, the city sought to maximize development. Artists’ renditions accompanying the plan depicted dense concentrations of three-story office buildings and up to 2,500 residential units that, according to one observer, would have ended up “submerging the historic properties in a sea of new privately owned residences.”

A clause in the original 1838 deed makes it clear, however, that it is the Commonwealth of Virginia, not the city of Hampton, that will take over possession of Fort Monroe. In 2007, the state legislature created the Fort Monroe Federal Area Development Authority (FMFADA). Bill Armbruster, FMFADA’s executive director, acknowledges that rumors of the fort’s fate have run rampant. “A number of scenarios have been put out there, and some of the early ideas did call for new dense urban development,” says the former Pentagon official. “I even heard a rumor of casinos. But the rumors are just not true.”

In 2008, then-Governor Tim Kaine called on FMFADA to produce a reuse plan in which “revenue maximization” was not “goal one.” The plan, signed by the governor in August 2008, calls for preservation of the core of the fort site as well as some new construction focusing on residential units, office space and “hospitality services,” which would, according to Armbruster, be leased to help raise operating funds. The plan also calls for preservation of nearly 40 percent of the site as green space. “We believe we can maintain the historic fabric of this place and make Fort Monroe a vibrant, self-sustaining destination—the two are not incompatible.”

“The FMFADA reuse plan is a step in the right direction,” says Mark Perreault, president of Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park. But even that plan, he says, leaves several major questions unanswered. One of these is the fate of the Wherry Quarter, a 100-acre parcel of land where mid-20th century housing is likely to be removed. Many hope that it will be restored to open space, marshlands, and beach-front property, and once again become the heart of Old Point Comfort. The plan labels the future of this section as “undetermined.” “That’s better than having it slated for development,” says Perreault, “but it also leaves a critical part of the future of the fort undefined and unprotected.”

An even bigger question mark revolves around something the FMFADA plan did not address: What role should the National Park Service play in the future of Freedom’s Fortress?

Fort Monroe National Park?

“Fort Monroe is a national treasure,” says Stephen Corneliussen, a long-time resident and vice president of Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park. “It is grand public place that belongs to all of us, and the National Park Service is the only agency with the experience and expertise to take on the challenge of its protection and interpretation.”

That challenge is a big one—570 acres with more than 250 buildings, a mile-long moat, a 322-slip marina, three miles of promenade, an 85-acre wetland, not to mention an estimated $4-million annual operating budget. A May 2008 Park Service Reconnaissance Study acknowledges that daunting challenge by stating that while “the resources of Fort Monroe are likely to meet the criteria for national significance and suitability as a potential unit of the National Park System,” it is unlikely that the Park Service is in a position to take over management of the entire 570-acres or even the smaller 63-acre moated fort without “a strong and financially sustainable partner to contribute to the costs of managing, maintaining, and operating” the fort and grounds.

With a potential for up to 2 million square feet of leasable commercial space, more than 300 residential units, and an annual visitation of up to 250,000, the site could be part of a “strong and financially sustainable” partnership, says Corneliussen. “The problem is that if you say ‘national park,’ some people take that to mean that nothing changes whatsoever, that a velvet rope is placed across the gateway and all you can do is gaze adoringly at what existed in the past. That’s not what we have in mind at all.”

Some people have pointed to California’s Presidio as a potential model, but Perreault says the Presidio model is not simply an “overlay” for any potential new park unit at Fort Monroe, citing differences in real estate values, ownership, and the lack of a federal trust to act as seed money. “We have to think outside the moat here,” he says. “A solid, strong presence of the National Park Service is critical. Uncle Sam, through the National Park Service, should be a principal player at Fort Monroe. It is something the nation built. It is a part of our history, and so its protection should be seen as a national obligation.”

Whatever form it takes, engaging the Park Service in the future of Fort Monroe is an idea that is catching on. A recent poll in the Virginian-Pilot, the newspaper that serves the Hampton Roads area, revealed that 86 percent of local citizens like the idea of a new national park. FMFADA, under the direction of Bill Armbruster, recently voted unanimously to pursue a strong Park Service presence and will work closely with Congress to draft the necessary legislation. Even the city of Hampton, whose original plan led some to fear the fort would be lost, recently passed a resolution that envisions “the National Park Service playing a major, active role in the reuse of Fort Monroe and urges a specific emphasis on the unique history of African Americans at Fort Monroe including especially the Contraband Slave Story.”

“This is our Ellis Island,” says Gerri Hollins, a descendant of a “contraband” slave and a founder of the Contraband Historical Society. “It is a place that marks both the beginning of slavery and the beginning of the end of slavery in this country. More people need to understand what happened here and its value in American history.” Just what form that story will be told in and who will be responsible for its telling are yet to be decided. “It is really about finding what will work best for this place rather than having preconceived notions about one model or another that may have been used elsewhere,” says Kathleen Kilpatrick, head of Virginia’s Department of Historic Resources. “It is a question of finding the right model even if it means striking out on your own.” A fitting image for a place where three men changed the course of American history by striking out on their own in search of freedom. [source: National Park Conservation Association Magazine, Jeff Rennicke teaches environmental literature classes at Conserve School in Wisconsin’s North Woods.]

Kingdom by the Sea - Fortress Monroe