Draft wheel (ca. 1863) -- Civil War draft wheel; cylindrical drum with a rectangular, lockable hatch and an iron and wood handle, set on trestle frame with bracket feet and a turned stretcher; brass plaque on side; with 100+ cards with names of draft-eligible men. (source: New-York Historical Society)

From the University of Chicago Press. "The New York City Draft Riots of 1863; An excerpt from

In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863," by Leslie M. Harris -- In September of 1862, President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation, which would take effect January 1, 1863, and free slaves in those states or regions still in rebellion against the Union. If any southern state returned to the Union between September and January, whites in that state theoretically would not lose ownership of their slaves. Despite its limits, free blacks, slaves, and abolitionists across the country hailed it as one of the most important actions on behalf of freedom in the nation's history. The Emancipation Proclamation brought formal recognition that the war was being fought, at least in part, on behalf of black freedom and equality.

The enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 capped two years of increasing support for emancipation in New York City. Although Republicans attempted to keep abolitionists from taking a leading role in New York's antislavery politics during the early years of the war, by 1862 abolitionist speakers drew huge audiences, black and white, in the city. Increasing support for the abolitionists and for emancipation led to anxiety among New York's white proslavery supporters of the Democratic Party, particularly the Irish. From the time of Lincoln's election in 1860, the Democratic Party had warned New York's Irish and German residents to prepare for the emancipation of slaves and the resultant labor competition when southern blacks would supposedly flee north. To these New Yorkers, the Emancipation Proclamation was confirmation of their worst fears. In March 1863, fuel was added to the fire in the form of a stricter federal draft law. All male citizens between twenty and thirty-five and all unmarried men between thirty-five and forty-five years of age were subject to military duty. The federal government entered all eligible men into a lottery. Those who could afford to hire a substitute or pay the government three hundred dollars might avoid enlistment. Blacks, who were not considered citizens, were exempt from the draft.

In the month preceding the July 1863 lottery, in a pattern similar to the 1834 anti-abolition riots, antiwar newspaper editors published inflammatory attacks on the draft law aimed at inciting the white working class. They criticized the federal government's intrusion into local affairs on behalf of the "nigger war." Democratic Party leaders raised the specter of a New York deluged with southern blacks in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation. White workers compared their value unfavorably to that of southern slaves, stating that "[we] are sold for $300 [the price of exemption from war service] whilst they pay $1000 for negroes." In the midst of war-time economic distress, they believed that their political leverage and economic status was rapidly declining as blacks appeared to be gaining power. On Saturday, July 11, 1863, the first lottery of the conscription law was held. For twenty-four hours the city remained quiet. On Monday, July 13, 1863, between 6 and 7 A.M., the five days of mayhem and bloodshed that would be known as the Civil War Draft Riots began.

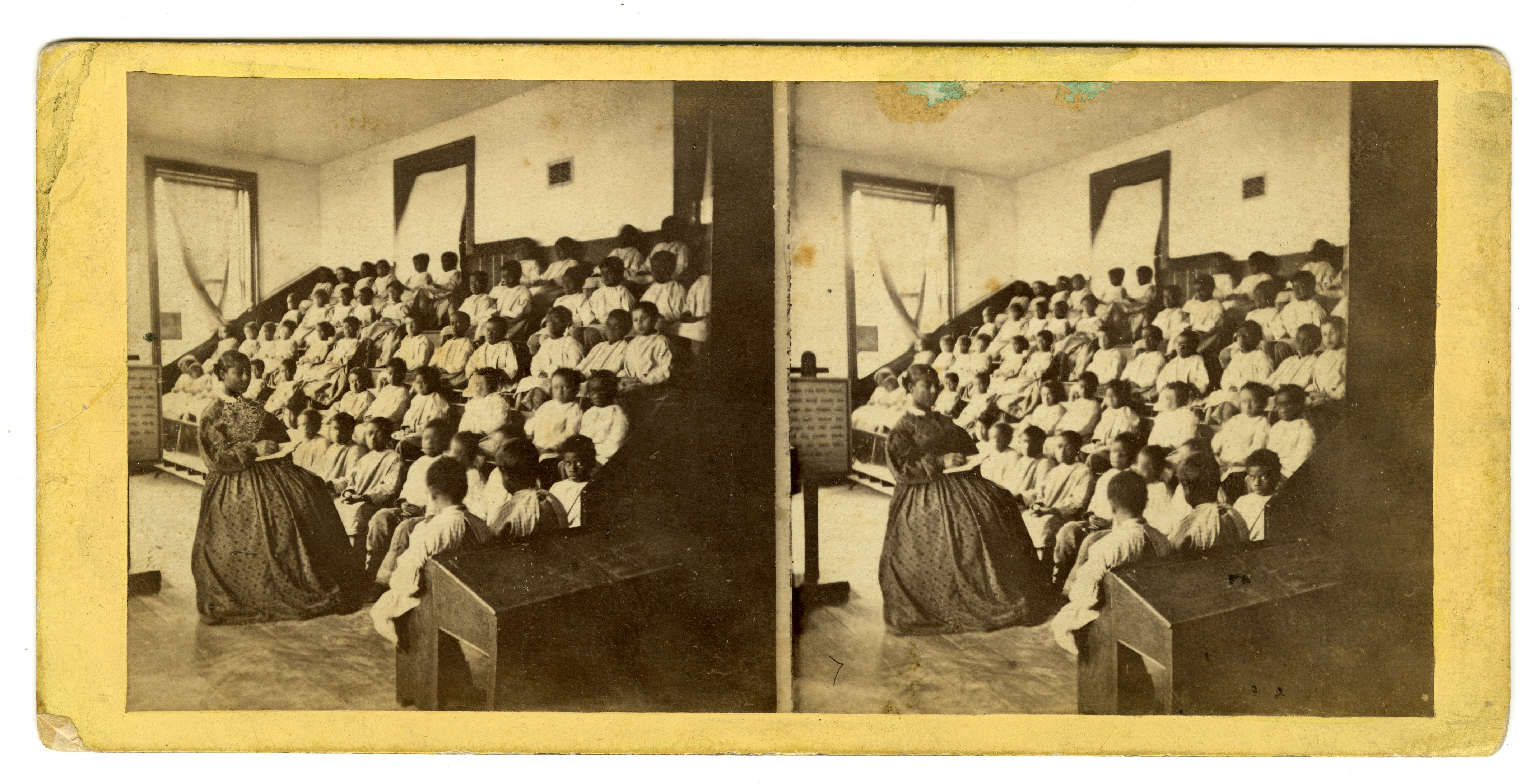

The rioters' targets initially included only military and governmental buildings, symbols of the unfairness of the draft. Mobs attacked only those individuals who interfered with their actions. But by afternoon of the first day, some of the rioters had turned to attacks on black people, and on things symbolic of black political, economic, and social power. Rioters attacked a black fruit vendor and a nine-year-old boy at the corner of Broadway and Chambers Street before moving to the Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue between Forty-Third and Forty-Fourth Streets. By the spring of 1863, the managers had built a home large enough to house over two hundred children. Financially stable and well-stocked with food, clothing, and other provisions, the four-story orphanage at its location on Fifth Avenue and Forty-Second Street was an imposing symbol of white charity toward blacks and black upward mobility. At 4 P.M. on July 13, "the children numbering 233, were quietly seated in their school rooms, playing in the nursery, or reclining on a sick bed in the Hospital when an infuriated mob, consisting of several thousand men, women and children, armed with clubs, brick bats etc. advanced upon the Institution." The crowd took as much of the bedding, clothing, food, and other transportable articles as they could and set fire to the building. John Decker, chief engineer of the fire department, was on hand, but firefighters were unable to save the building. The destruction took twenty minutes.

In the meantime, the superintendent and matron of the asylum assembled the children and led them out toForty-Fourth Street. Miraculously, the mob refrained from assaulting the children. But when an Irish observer of the scene called out, "If there is a man among you, with a heart within him come and help these poor children," the mob "laid hold of him, and appeared ready to tear him to pieces." The children made their way to the Thirty-Fifth Street Police Station, where they remained for three days and nights before moving to the almshouse on Blackwell's Island—ironically, the very place from which the orphanage's founders had hoped to keep black children when they built the asylum almost thirty years earlier.

The Irish man who castigated the mob for not helping the black children was not the only white person punished by rioters for seeming overly sympathetic to blacks. Throughout the week of riots, mobs harassed and sometimes killed blacks and their supporters and destroyed their property. Rioters burned the home of Abby Hopper Gibbons, prison reformer and daughter of abolitionist Isaac Hopper. They also attacked white "amalgamationists," such as Ann Derrickson and Ann Martin, two women who were married to black men; and Mary Burke, a white prostitute who catered to black men. Near the docks, tensions that had been brewing since the mid-1850s between white longshoremen and black workers boiled over. As recently as March of 1863, white employers had hired blacks as longshoremen, with whom Irish men refused to work. An Irish mob then attacked two hundred blacks who were working on the docks, while other rioters went into the streets in search of "all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers . . . they could find." They were routed by the police. But in July 1863, white longshoremen took advantage of the chaos of the Draft Riots to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from area near the docks. White dockworkers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to blacks; mobs stripped the clothing off the white owners of these businesses.

Black men and black women were attacked, but the rioters singled out the men for special violence. On the waterfront, they hanged William Jones and then burned his body. White dock workers also beat and nearly drowned Charles Jackson, and they beat Jeremiah Robinson to death and threw his body in the river. Rioters also made a sport of mutilating the black men's bodies, sometimes sexually. A group of white men and boys mortally attacked black sailor William Williams—jumping on his chest, plunging a knife into him, smashing his body with stones—while a crowd of men, women, and children watched. None intervened, and when the mob was done with Williams, they cheered, pledging "vengeance on every nigger in New York." A white laborer, George Glass, rousted black coachman Abraham Franklin from his apartment and dragged him through the streets. A crowd gathered and hanged Franklin from a lamppost as they cheered for Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president. After the mob pulled Franklin's body from the lamppost, a sixteen-year-old Irish man, Patrick Butler, dragged the body through the streets by its genitals. Black men who tried to defend themselves fared no better. The crowds were pitiless. After James Costello shot at and fled from a white attacker, six white men beat, stomped, kicked, and stoned him before hanging him from a lamppost.

With these actions white workers enacted their desires to eradicate the working-class black male presence from the city. The Longshoreman's Association, a white labor union, patrolled the piers during the riots, insisting that "the colored people must and shall be driven to other parts of industry." But "other parts of industry," such as cartmen and hack drivers, not to mention skilled artisans, also sought to exclude black workers. The riots gave all these workers license to physically remove blacks not only from worksites, but also from neighborhoods and leisure spaces. The rioters' actions also indicate the degree to which the sensational journalists and reformers of the 1840s and 1850s had achieved their goals of convincing whites, and particularly the Irish, that interracial socializing and marriage were evil and degrading practices. The riots unequivocally divided white workers from blacks. The act of rioting may itself have released guilt and shame over former interracial pleasures. Finally, and most simply, white workers asserted their superiority over blacks through the riots. The Civil War and the rise of the Republican Party and Lincoln to power indicated to New York's largely Democratic white workers a reversal of power in the nation; black labor competition indicated a reversal of fortunes in New York City itself. White workers sought to remedy their upside-down world through mob violence.

Ironically, the most well known center of black and interracial social life, the Five Points, was relatively quiet during the riots. Mobs neither attacked the brothels there nor killed black people within its borders. There were also instances of interracial cooperation. When a mob threatened black drugstore owner Philip White in his store at the corner of Gold and Frankfurt Street, his Irish neighbors drove the mob away, for he had often extended them credit. And when rioters invaded Hart's Alley and became trapped at its dead end, the black and white residents of the alley together leaned out of their windows and poured hot starch on them, driving them from the neighborhood. But such incidents were few compared to the widespread hatred of blacks expressed during and after the riots.

In all, rioters lynched eleven black men over the five days of mayhem. The riots forced hundreds of blacks out of the city. As Iver Bernstein states, "For months after the riots the public life of the city became a more noticeably white domain." During the riots, landlords drove blacks from their residences, fearing the destruction of their property. After the riots, when the Colored Orphan Asylum attempted to rebuild on the site of its old building, neighboring property owners asked them to leave. The orphanage relocated to 51st Street for four years before moving into a new residence at 143rd Street between Amsterdam and Broadway, in the midst of what would become New York's predominantly black neighborhood in the twentieth century, Harlem. But in 1867, the area was barely settled and far removed from the center of New York City. Black families also fled the city altogether. Albro Lyons, keeper of the Colored Sailors' Home, was able to protect the boardinghouse on the first day of the riots, but soon fled to the neighborhood police station to seek an escort from the city for his wife and family. An officer accompanied the Lyons family to the Sailors' Home, where they gathered up what belongings they could carry before boarding the Roosevelt Street ferry, which took them to Williamsburg in Brooklyn. "From the moment they put foot on the boat, that was the last time they ever resided in New York City, leaving it forever." Other blacks fled to New Jersey and beyond. By 1865, the black population had plummeted to just under ten thousand, its lowest since 1820.

Those blacks who remained in the city found a somewhat chastened elite eager to help New York's black residents recover in the aftermath of the riots. The seven-month-old Union League Club (which had as one of its main tenets black uplift) and the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People spearheaded relief efforts to blacks, providing forty thousand dollars to almost twenty-five hundred riot victims and finding new jobs and homes for blacks. Just under a year later, Republican elites and New York City blacks publicly celebrated their renewed alliance. In December of 1863, the secretary of war gave the Union League Club permission to raise a black regiment. The Union League Club decided to march the regiment of over one thousand black men through the streets of New York to the Hudson River, where the ship that would take them south waited. On March 5, 1864, before a crowd of one hundred thousand black and white New Yorkers, the black regiment processed, making "a fine appearance in their blue uniform, white gloves and white leggings." They were preceded by the police superintendent, one hundred policemen, the Union League Club itself, "colored friends of the recruits," and a band. In a powerful display, the parade publicly linked blacks with the leaders of the new order being ushered in by the Civil War.

But the event could not completely erase the racial concerns that had been part of the draft riots, if indeed its organizers sought to. One account said of the soldiers, "a majority of them are black; indeed there are but few mulattoes among them," an attempt to downplay the obvious fears of racial mixing that white workers displayed before and during the riots, fears which many white elites may have shared. Observers also used the event to contrast the loyalty of blacks to the Union and their good behavior with the recent rioting as well as the general culture of white workers: "The 20th is emphatically an African regiment, and to its credit be it spoken, not one of its members disobeyed orders, no one broke ranks to greet enthusiastic friends, no one used intoxicating drinks to excess, no one manifested the least inclination to leave the service, and their marching was very creditable." The New York elite presented the black troops as symbols of the new orderly working class they desired: sober, solemn, obedient, and dedicated to the Union cause. But such simple symbolism obscured the complex divisions of status, class, outlook and aspiration that had been part of New York's free black community from its inception.

As the Union Army marched south, it brought with it black and white abolitionists (many affiliated with the American Missionary Assocition, others independent of organized efforts) who sought to reform southern blacks during and after the war. These largely middle-class activists carried ideas of racial uplift first promulgated in the northeast, from creating manual labor schools to moral reform to enhancing wage labor. They encountered newly free blacks eager for educational and economic betterment, but just as certainly shaping their own definitions of independence and equality. During the Civil War and Reconstruction years, black and white people from urban and rural areas in the north and south were challenged to create new opportunities for the freed people. But New York City had never unified to overcome the problems of racism and fully embrace black freedom; neither would the nation.

white people are evil as hell

ReplyDeleteRe read article: good people exist. Find them and fight with them against the evil.

ReplyDeleteFreedomPop is UK's only ABSOLUTELY FREE mobile phone provider.

ReplyDeleteWith voice, text & data plans always start at £0.00/month (100% FREE).