From the New York Times Opinionator , "Black New York and the Draft Riots ," by Kevin McGruder, on 26 July 2013 -- Reflecting on New York City’s tumultuous summer of 1863, the Rev. Charles Bennett Ray, pastor of Bethesda Congregational Church on Sullivan Street in Manhattan, noted later that year:

But when we had concluded our work with the Relief Committee, our missionary work with these still suffering people was not done; with some of them it had just begun. Their claims for household goods were still unpaid, and they were destitute of everything needful for use and comfort. None know, excepting those who have witnessed it, the extent of the suffering among them.

The “suffering people” were African-Americans affected by the New York City Draft Riots, which occurred over four days in July of 1863 and dominated the lives of black New Yorkers during the rest of that summer. In the aftermath, Ray, the Rev. Henry Highland Garnet and other black clergymen dispensed aid to those in need and collaborated with local newspapers to convey to white and black New Yorkers a desire to move forward living in an atmosphere of fairness.

A broad range of issues, some decades in the making, related to slavery, abolition, social class, politics, ethnicity, race, labor and capital inspired the riots that summer of 1863. As a city of commerce, many New York merchants had strong financial ties with the southern planter class against whom the Civil War, begun in 1861, was being waged. As a Northern bastion of the Democratic Party, many New York Democrats opposed the Civil War and sympathized with their fellow Democrats in the South. But New York was also a center of abolitionism, with the city’s presses producing thousands of antislavery tracts, and its churches and other meeting houses for decades served as gathering places for meetings denouncing slavery. By the 1860s New York had also become a base of the new antislavery Republican Party.

The spark for the New York City Draft Riots was the federal Conscription Act, the nation’s first draft, passed by Congress in March 1863. Two years into the Civil War, with desertions, tens of thousands of battlefield deaths and an equal number of deaths from disease, more troops were needed for the Union Army than were being supplied by volunteers. The conscription law targeted men between the ages of 20 and 35, and all unmarried white men up to the age of 45 for military service. The provision that enabled draftees to be released from service by paying $300 (a year’s wages for some) to a replacement ensured that the draft would target lower-income men. Many white working men in New York took this fact as proof of the rumors that, once they were drafted, their jobs would be taken by black men.

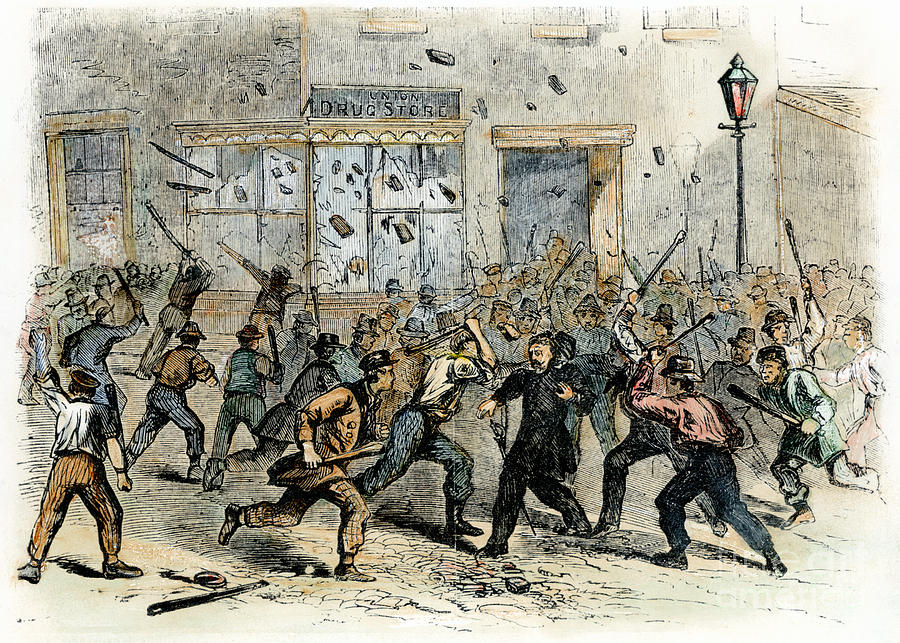

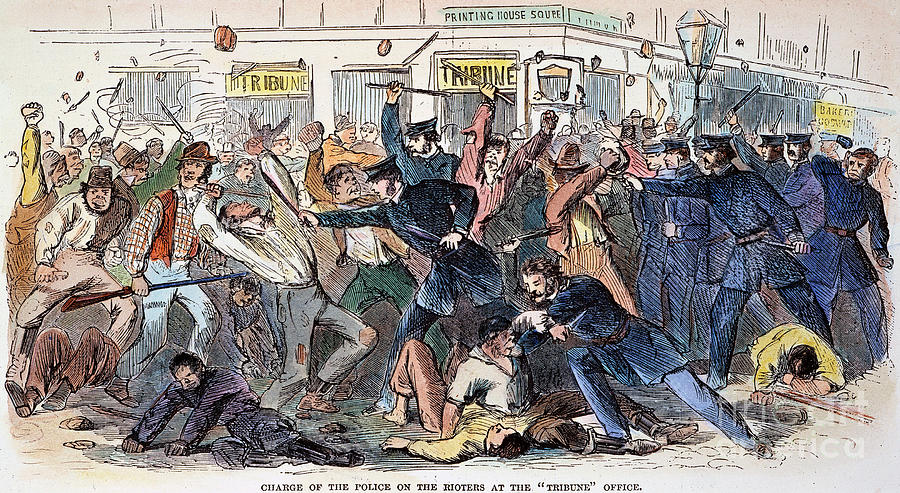

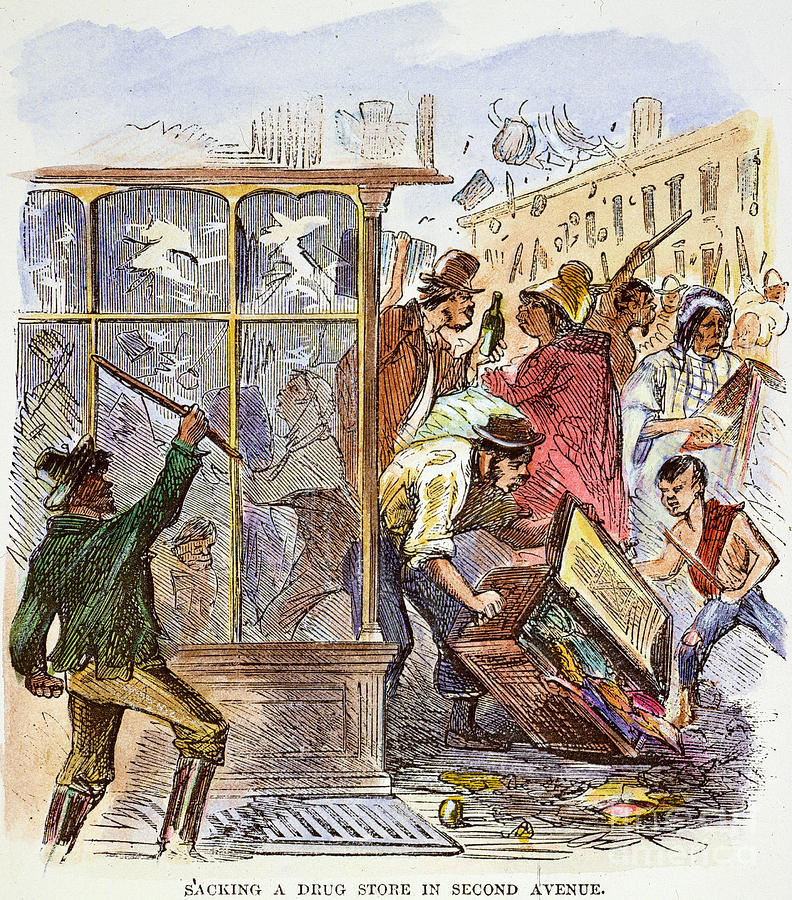

The draft selection began routinely on Saturday, July 11, and was scheduled to continue on Monday morning. But hundreds of white working men mobbed the draft office at Third Avenue and 47th Street and destroyed the office. Over the next four days, groups of men (and some women) moved about the city, looting stores and burning warehouses and the homes of African-Americans, white abolitionists and any businesses that were thought to be sympathetic to blacks. Any black person caught in the mob’s path was clubbed, stabbed, hanged or burned, and in some cases a combination of all four. Many of the male victims were sexually mutilated, and their toes or fingers cut off for trophies. New York’s recently elected Republican mayor, George Opdyke, issued a proclamation declaring New York City to be “in a state of insurrection.”

The police as well as militia units based in Manhattan scrambled to thwart rioters. By Thursday, the fourth day of the rioting, the first of several Union Army regiments arrived in New York from the South. By Saturday, 10 regiments were in the city, sent north under orders from the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

Although the peak of the violence had passed, the city was still unsafe. A comprehensive survey of the damage began. Estimates of white and black people killed in the four days of rioting ranged from 74 to 1,200. Property valued at $5 million was destroyed, and it was estimated that 3,000 black residents (out of a black population of 12,000, and total city population of 800,000) had no place to live. For black New Yorkers, the riots shattered any sense of stability that they may have had.

New York’s white civic leaders moved quickly into action to organize relief efforts, under the auspices of the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People Suffering from the Late Riots. The Relief Committee hired a general agent, Vincent Colyer, and an office was opened on Fourth Street. Notices were placed in newspapers notifying victims of the process for obtaining assistance.

A panel of African-American ministers, including Ray and Garnet, pastor of the African-American congregation at Shiloh Presbyterian Church, located at Prince and Marion Streets, were appointed by the committee to make home visits to those seeking aid and to determine the truthfulness of their requests. They were good choices: a former editor of The Colored American newspaper, Ray had a reputation that extended beyond New York City, as did Garnet. His 1843 “Address to the Slaves,” a call to resistance which he made at the National Convention of Colored Men in Buffalo, brought him to the attention of leaders in the black community across the country.

The clergy reached out to the black community through home visits as well as newspaper announcements. In the July 21 edition of Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune, Garnet offered a message of thanks under the heading “The Colored People of New York to Their Friends.” Indicating that the message was offered at the “request of many of the colored citizens of New York” to the “portion of the city press which counseled observance of the law,” to the police officers who provided protection, to the “ladies and gentlemen who sheltered our wives and little children,” and to ministers of every denomination, it noted that “we wish our persecutors no harm.”

This message seems to have been more than a simple note of gratitude. While its tone was consistent with the Christian ethos of forgiveness, Garnet’s reference to “the portion of the city press” that encouraged lawfulness alludes to the common belief, prominent at the time in the black community and elsewhere, that some elements of the press had incited the rioters. A critical purpose of the message could also have been to reassure white New Yorkers that black New Yorkers would not seek revenge leading to a cycle of violence.

Garnet’s same message appeared in the July 25 edition of the New York weekly The Anglo-African. The editor, Robert Hamilton, and his brother Thomas had established The Anglo-African in New York City in 1859 with the motto on its masthead announcing that “Man must be free, if not through the law, then above the law.” Since that paper’s readership was predominantly black, the purpose of reprinting the message of thanks to the white community in that paper could have been to inform the black community that there were white New Yorkers who had assisted some blacks in the midst of the riots, even if that had not been the personal experience of the readers, and to send the signal to black residents that seeking revenge would not benefit the black community.

The Merchant’s Committee ultimately raised over $40,000 from individuals and groups, including Sunday school classes and church congregations of all denominations within the city and from other parts of the country, and assisted over 12,000 people. The Committee formally completed its work with a meeting on Aug. 22, at which the black clergymen provided the committee with a proclamation of thanks for their assistance that included the following request:

If in your temporary labors of Christian philanthropy, you have been induced to look forward to our future destiny in this our native land, and to ask what is the best thing we can do for the colored people? This is our answer. Protect us in our endeavors to obtain an honest living. Suffer no one to hinder us in any department of well directed industry, give us a fair and open field and lets us work out our own destiny, and we ask no more.

Nevertheless, the black population of New York City declined dramatically after the draft riots. In the census of 1860, New York’s black population was 12,414; by 1865 it was estimated at 9,945. While other Northern cities, including Boston and Detroit, experienced racial violence sparked by the inception of the draft, no response was as virulent as New York City’s four days of rioting. The draft, suspended due to the riots, resumed on August 19, and with the military presence in the city continuing, it proceeded in an orderly fashion. But as suggested in Ray’s report to the American Missionary Association, the deep effects of the draft riots would require a much longer period to be overcome. (source: The New York Times; Copyright 2013 The New York Times Company)

No comments:

Post a Comment