The Patent Office, c. 1855, Edward Sachse and Co. chromolithograph, From the original in the National Portrait Gallery Smithsonian Institution

From Bloomberg, "How the Patent Office Helped to End Slavery," by Sean Vanatta, on Febuary 2013 -- It is easy to look to early America as a moment of unshackled innovation. Yet in this respect the pre-Civil War period was especially problematic.

Then, intellectual property and human property were dual and dueling pillars of capitalist development, and for a vast swath of the population, invention was stifled under the crushing weight of slavery.

Benjamin Montgomery, a slave inventor.

In the years before the outbreak of the Civil War -- the historical record is not clear exactly when -- the future president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, filed a patent claim on an improved riverboat propeller with the U.S. Patent Office. The novel design promised both increased efficiency and improved maneuverability compared with the paddlewheels then favored by most river steamships. His claim, however, was summarily denied.

Davis is remembered for many things, though not for being an accomplished inventor, and for good reason: The improved propeller wasn’t his to patent. Instead, it was the work of Benjamin Montgomery, a slave on the plantation of Davis’s brother Joseph.

Joseph Emory Davis was Jefferson Davis' eldest brother and mentor.

Slave Owner

After the patent office turned down Jefferson Davis’s claim, Joseph tried his luck, applying for a patent on the propeller and making clear, as Jefferson had, that it was Montgomery’s design. Since Montgomery was Joseph Davis’s human property, Joseph had every reason to expect that the Patent Office would accept his claim. Naturally, as one slave owner phrased it, “no one could rationally doubt, that in legal contemplation, the master has the same right to the fruits of the labor of the intilect [sic] of his slave, that he has to those of his hand.”

Commissioner of Patents Joseph Holt

No one, that is, except U.S. Commissioner of Patents Joseph Holt.

Unfortunately for the Davis brothers, Holt ruled in 1857 that slave inventions couldn’t be patented under existing law. As a slave, Montgomery wasn’t a citizen and was therefore “legally incompetent,” in Holt’s words, to file a claim on his own. At the same time, because neither Jefferson nor Joseph Davis was the “true and original inventor” of Montgomery’s propeller, neither could file a claim on the slave’s behalf and thus legally protect the invention.

In effect, slaves’ intellectual property simply didn’t exist. This posed a significant problem, not only for the Davis brothers, but for any slave owner who sought to protect and profit from slaves’ inventions. On the eve of the Civil War, several slaveholders met with similarly negative responses from the Patent Office. For these Southerners, their prerogatives as slave owners (-to maintain a legal system that inscribed the inferiority of slaves),- and as capitalists (-to profit from the judicious employment of their capital),- were thrown into conflict by Holt’s patent ruling.

Still, the Davis brothers could have simply claimed Montgomery’s inventions as their own. Evidence suggests that Eli Whitney’s cotton gin and Cyrus McCormick’s reaper, both landmark antebellum inventions, were at least partially the products of slave intellectual labor. The Davis brothers took a different approach, asserting the intellectual capabilities of slaves such as Montgomery, while trying to claim the profits of that ingenuity as their own.

Confederate Law

The creation of the Confederacy, though, offered slaveholders a chance to square this circle. Through their new government, Southerners sought to institute legal structures that would allow them to deploy their human capital most efficiently -- whether toward manual or intellectual labor -- securing for slave owners the profits from that work.

With Jefferson Davis at the helm, the Confederate States enacted a patent law in 1861 that formalized slaveholders’ ownership of slave inventions.

If the “original inventor” was a slave, the act read, the owner of the slave may “have all the rights to which a patentee is entitled by law.”

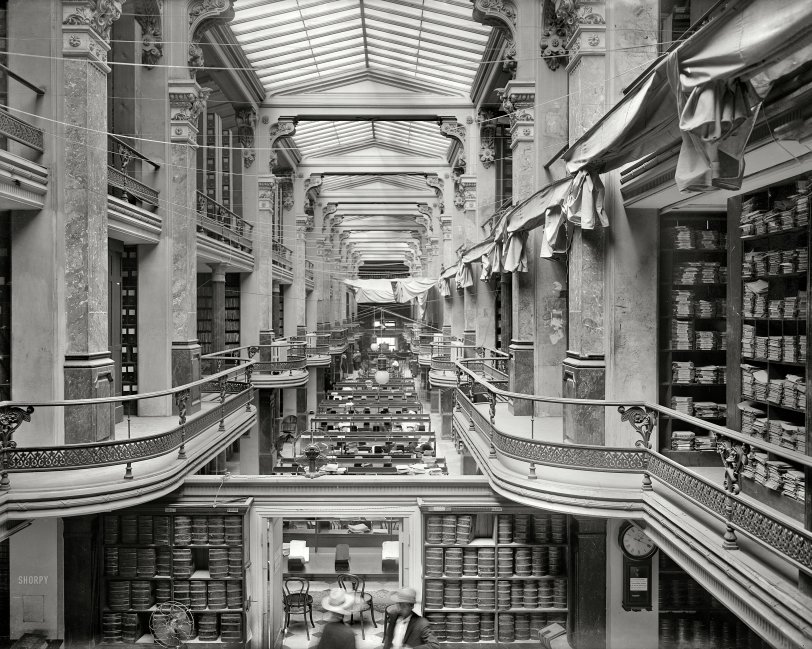

Unites States Troops bunking at the US Patent Office during the Civil War.

Such legislative labors ultimately proved unnecessary. Of 274 patents issued by the Confederate Patent Office from August 1861 to March 1865 -- including improvements to rifle and cannon technology, submarine and torpedo models, and a new type of artificial leg -- none appears to have been the product of slaves. Montgomery’s case proved to be a rare exception.

Still, even after the war, some Southerners continued to promote and seek profit from the ideas of onetime slaves. One Southerner marketed a novel agricultural implement using the following testimonial: “I am glad to know this implement is the invention of a negro slave -- thus giving the lie to the abolition cry that slavery dwarfs the negro mind. When did a free negro ever invent anything?”

The long history of African-American invention need not be recounted here to demonstrate the falsehood of this statement. Conversely and unsurprisingly, abolition greatly increased the rate of black inventiveness, and led to what one scholar has called “a burst of patents.” Clearly, the promise of owning their own intellectual property prompted African-Americans to pursue innovation in their own interests.

[source: Bloomberg (Sean Vanatta is a graduate student at Princeton University. The opinions expressed are his own.) ®2013 BLOOMBERG L.P. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

From Wikipedia --Ben Montgomery was born into slavery in 1819 in Loudon County, Virginia. He was sold to Joseph E. Davis, a Mississippi planter. Davis was the older brother of Jefferson Davis who would later serve as the President of the Confederate States of America. After a period time, Davis could see great talent within Montgomery and assigned to him the responsibility of running his general store on the Davis Bend plantation. Montgomery, who by this time had learned to read and write (he was taught by the Davis children), excelled at running the store and served both white customers and slaves who could trade poultry and other items in return for dry goods. Impressed with his knowledge and abilities to run the store, Davis placed Montgomery in charge of overseeing the entirety of his purchasing and shipping operations on the plantation.

In the year of 1837, before the outbreak of the Civil War, Montgomery was sold as a slave to Joseph Emory Davis. Davis' brother, Jefferson Davis, later became the President of the Confederate States of America. Prior to the war, Montgomery managed a general store on the Davis Bend plantation in Mississippi, where slaves could trade for dry goods and where whites could purchase the items traded in by the slaves. It was unusual for a slave to serve in this position.

Taught to read and write by his owners, Montgomery eventually became responsible for overseeing the entire purchasing and shipping operations of the plantation. The Davis family taught him many skills including land surveying, flood control, and architecture.

On May 21, 1847, Montgomery's son, Isaiah Montgomery, was born. Due to Ben's favored position among the Davis Bend slaves by the Davis family, Isaiah was also given the opportunity of receiving an education. Montgomery maintained a close relationship with his son up until his death

In addition to being able to read and write, Montgomery also learned a number of other difficult tasks, including land surveying, techniques for flood control and the drafting of architectural plans. He was also a skilled mechanic and a born inventor. At the time commerce often flowed through the rivers connecting counties and states. With differences in the depths of water in different spots throughout the river, navigation could become difficult. If a steamboat were to run adrift, the merchandise would be delayed for days, if not weeks. [5]

Montgomery also worked as an inventor. In the late 1850s he applied for a patent for his design of a steam operated propeller to provide propulsion to boats in shallow water. Davis decided to address the problem and created a propellor that could cut into the water at different angles, thus allowing the boat to navigate more easily though shallow water. This was not a new invention, but an improvement on similar designs invented by John Stevens in 1804 and John Ericsson in 1838.(U.S. Patent 588) On June 10, 1858, on the basis that Ben, as a slave, was not a citizen of the United States, and thus could not apply for a patent in his name, he was denied this patent application in a ruling by the United States Attorney General's office, on the grounds that neither slaves nor their owners could receive patents on inventions devised by slaves.[6] Later, both Joseph and Jefferson Davis attempted to patent the device in their names but were denied because they were not the "true inventor." Ironically, when Jefferson Davis later assumed the Presidency of the Confederacy, he signed into law the legislation that would allow a slaves to receive patent protection for their inventions. On June 28, 1864, Montgomery, no longer a slave, filed a patent application for his devise, but the patent office again rejected his application.

Following the end of the American Civil War, Joseph Davis sold his plantation and property to Montgomery, in 1866, for the sum of $300,000 as part of a long-term loan. With his son Isaiah, Montgomery established a general store known as Montgomery and Sons. Montgomery worked towards his lifelong dream of establishing a community for freed slaves. He never lived to see his dream come to fruition. Catastrophic floods ruined the crops, and, when Montgomery failed to make a payment on the loan in 1876, Davis Bend automatically reverted to the Davis family as per the terms of the original contract. Heartbroken, Montgomery died the next year.

However, after his father's death, Montgomery's son Isaiah purchased 840 acres (3.4 km2) between the Vicksburg and Memphis railroad lines for the purpose of establishing the community of freed slaves his father dreamed of. Along with other former slaves, Isaiah Montgomery established the town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi in 1887. (source: Wikipedia)

In the year of 1837, before the outbreak of the Civil War, Montgomery was sold as a slave to Joseph Emory Davis. Davis' brother, Jefferson Davis, later became the President of the Confederate States of America. Prior to the war, Montgomery managed a general store on the Davis Bend plantation in Mississippi, where slaves could trade for dry goods and where whites could purchase the items traded in by the slaves. It was unusual for a slave to serve in this position.

Taught to read and write by his owners, Montgomery eventually became responsible for overseeing the entire purchasing and shipping operations of the plantation. The Davis family taught him many skills including land surveying, flood control, and architecture.

On May 21, 1847, Montgomery's son, Isaiah Montgomery, was born. Due to Ben's favored position among the Davis Bend slaves by the Davis family, Isaiah was also given the opportunity of receiving an education. Montgomery maintained a close relationship with his son up until his death

In addition to being able to read and write, Montgomery also learned a number of other difficult tasks, including land surveying, techniques for flood control and the drafting of architectural plans. He was also a skilled mechanic and a born inventor. At the time commerce often flowed through the rivers connecting counties and states. With differences in the depths of water in different spots throughout the river, navigation could become difficult. If a steamboat were to run adrift, the merchandise would be delayed for days, if not weeks. [5]

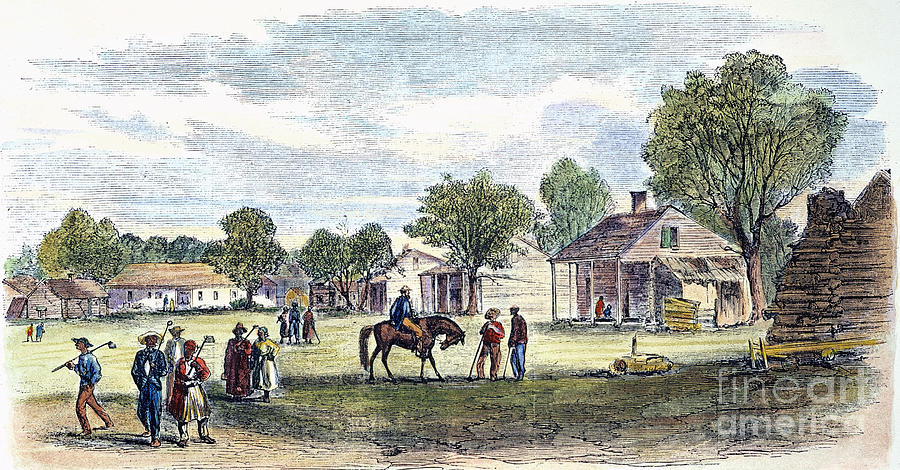

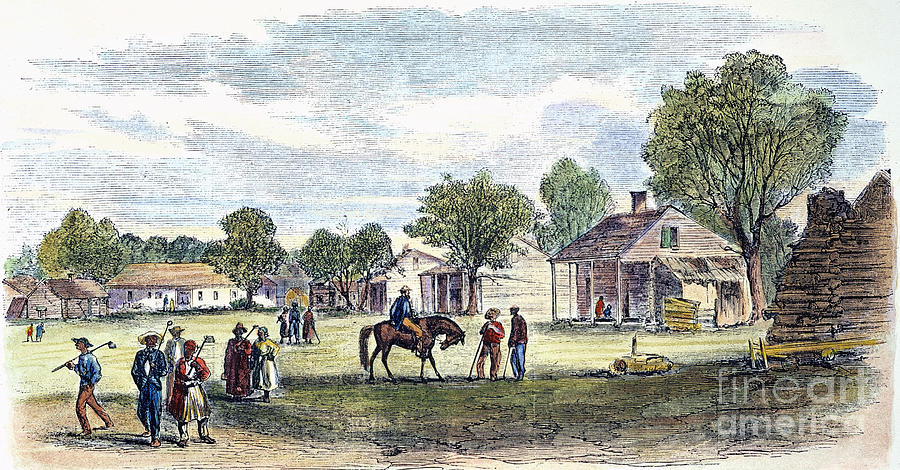

Slave quarters of Jefferson Davis' Plantation, Davis Bend, Mississippi

Montgomery also worked as an inventor. In the late 1850s he applied for a patent for his design of a steam operated propeller to provide propulsion to boats in shallow water. Davis decided to address the problem and created a propellor that could cut into the water at different angles, thus allowing the boat to navigate more easily though shallow water. This was not a new invention, but an improvement on similar designs invented by John Stevens in 1804 and John Ericsson in 1838.(U.S. Patent 588) On June 10, 1858, on the basis that Ben, as a slave, was not a citizen of the United States, and thus could not apply for a patent in his name, he was denied this patent application in a ruling by the United States Attorney General's office, on the grounds that neither slaves nor their owners could receive patents on inventions devised by slaves.[6] Later, both Joseph and Jefferson Davis attempted to patent the device in their names but were denied because they were not the "true inventor." Ironically, when Jefferson Davis later assumed the Presidency of the Confederacy, he signed into law the legislation that would allow a slaves to receive patent protection for their inventions. On June 28, 1864, Montgomery, no longer a slave, filed a patent application for his devise, but the patent office again rejected his application.

Following the end of the American Civil War, Joseph Davis sold his plantation and property to Montgomery, in 1866, for the sum of $300,000 as part of a long-term loan. With his son Isaiah, Montgomery established a general store known as Montgomery and Sons. Montgomery worked towards his lifelong dream of establishing a community for freed slaves. He never lived to see his dream come to fruition. Catastrophic floods ruined the crops, and, when Montgomery failed to make a payment on the loan in 1876, Davis Bend automatically reverted to the Davis family as per the terms of the original contract. Heartbroken, Montgomery died the next year.

However, after his father's death, Montgomery's son Isaiah purchased 840 acres (3.4 km2) between the Vicksburg and Memphis railroad lines for the purpose of establishing the community of freed slaves his father dreamed of. Along with other former slaves, Isaiah Montgomery established the town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi in 1887. (source: Wikipedia)

***

Click on the links below for more information on Issiah Montgomery, son of Ben Montgomery, former slaves of Jefferson and Joseph Davis:

No comments:

Post a Comment