From Bloomberg, "Foxconn Riot Shows Why Company Towns Often Grow Violent," by Hardy Green, on 3 October 2012 -- Labor unrest appears to be on the rise in China. Last month, as many as 2,000 workers skirmished with hundreds of police and security guards on the campus of the Taiwanese company Foxconn Technology Group. This 21st-century version of a company town within the industrial city of Taiyuan houses 79,000 workers who live in company-owned dorms, eat in company-owned cafeterias and put in long days on assembly lines.

Although it isn’t yet clear exactly how the riot started, resentment over poor conditions and aggressive guards almost certainly played a role. Such complaints are widespread in China’s company towns. They have an even longer history in the U.S., where such towns proliferated through the 19th and early 20th centuries.

These have generally fallen into two categories: paternalistic industrial Edens and exploitative shantytowns. Neither has been immune to violent protest.

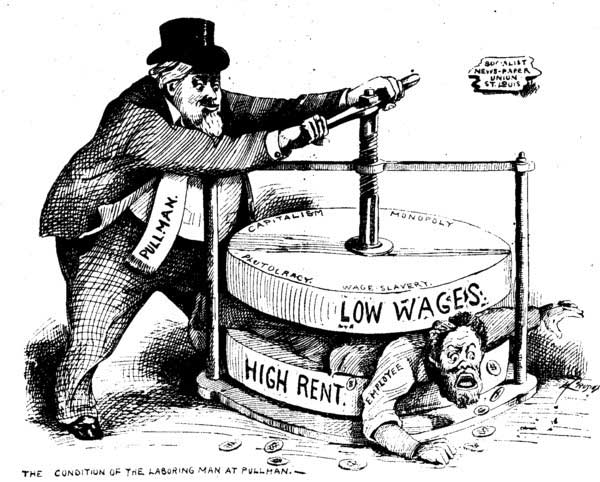

Pullman strike cartoon

Consider the experience of Pullman, Illinois, a model community erected for the production of railroad sleeping cars by the Pullman Palace Car Co. in the 1880s. Company founder George Pullman declared the site, some 14 miles outside of Chicago, to be an area free of “all baneful influences.” The complex included a 30-acre office-and-manufacturing works, a spectacular arcade for retailers, a library, a hotel and block upon block of row houses and tenements. As in most such company- owned burgs, government was firmly in the hands of the company.

Strike, Boycott

Then in 1893, with the company’s earnings at a record $11 million, the U.S. entered an economic depression. Wage reductions and layoffs followed, but the company refused to lower workers’ rents, which were deducted from paychecks. Pullman workers formed a union, went on strike and began a boycott, which went viral. Soon, 50,000 railroad workers across the country were at war with the company, sabotaging railroad tracks and attacking trains. In time, federal troops broke the strike, but the model town of Pullman was indelibly associated with industrial strife and became a symbol of failed paternalism. By the turn of the century, the town had entered an era of decline.

In the 1910s, plumbing-fixture maker Kohler Co. embarked on a similar experiment, constructing the settlement of Kohler Village on the edge of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. By the 1930s, the company’s works sprawled over 191 acres, complemented by 450 free-standing houses, a dorm and eating hall for unmarried employees, good schools, and a public auditorium. Workers were allowed to buy their homes, and Kohler supplemented its above- average wages with such perks as group life insurance and pensions.

But the Great Depression brought layoffs, reduced hours and wage garnishment that went to pay mortgages held by the Kohler Building & Loan Association. In 1934, striking workers clashed with village deputies armed with machine guns, tear gas and clubs. In the altercation, 49 strikers were wounded, two fatally. The conflict would eventually become one of the country’s longest-running labor disputes. For a time, the model village became synonymous with class warfare, marked by “needless and ruthless killing,” in the words of one federal mediator.

Appalachia’s sulfurous coal-company towns witnessed even greater violence. In 1921, thousands of union miners faced off against a 2,000-strong army of deputies and mine guards in what became known as the Battle of Blair Mountain; about 100 died. In the 1930s, Harlan County, Kentucky, saw an antiunion reign of terror marked by house bombings, shootings and mass arrests.

Right Combination

In all such cases, grievances over work and living conditions formed a combustible mix. But in a handful of locations (though obviously not in Kohler Village), managers found relief in a popular American tradition: home ownership and self government.

During the 1890s, the small Apollo Iron & Steel Co. erected its own model town, called Vandergrift, Pennsylvania, some 30 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. As in other industrial utopias, there were amenities, including modern sanitation, parkland and donated space for churches. Unlike most company towns, homes were privately owned by workers, who were carefully screened. Perhaps more important, unlike in Kohler Village, the residents were self-governing, electing a town council composed of skilled workers from the mill.

Vandergrift, Pennsylvania

The combination seemed to work for management: A 1901 strike called by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers fizzled in Vandergrift, where a union observer reported the workers to be “bound up by their property interests.” The trade journal Iron Age called the workers’ indifference to the strike “a crowning vindication” of the company’s approach to community and labor relations.

In China, home-ownership and self-government certainly don’t appear to be on the agenda. But as labor relations there grow more volatile, perhaps the Communist elite should begin pondering some subsidy for private housing as a means toward social peace.

(Hardy Green is the author of “The Company Town: The Industrial Edens and Satanic Mills That Shaped the American Economy.” The opinions expressed are his own.) [source: Bloomberg]

No comments:

Post a Comment