Guard at a Coal Mining Company Town. Coal mining interests in Alabama built company housing for workers, which were managed and controlled with heavy-handed tactics by corporate agents.

From the Economist, "Urban development in America: Monuments to power, The politics and culture of urban development," on 14 October 2010 -- COMPANY towns are both quintessentially American and supremely anti-American institutions. They are the corporate equivalents of cities on a hill, monuments to the power and creativity of America's corporate fathers. But at the same time they represent a triumph of the collective over the individual, places where the bosses owned the workers “heart, soul, skin and guts”, to borrow a phrase from Dashiell Hammett.

The Company Town: The Industrial Edens and Satanic Mills That Shaped the American Economy. By Hardy Green.

America has had more experience with company towns than any other country (though presumably China will eventually catch up with America in this, as in everything else). In this delightful book Hardy Green, a former editor at Business Week, tells the American story through these creations. Cotton kings planted them in New England. Coal barons scattered them across Appalachia. Motor moguls built supersized ones in the Midwest. At their height there were more than 2,500 such towns housing 3% of the population.

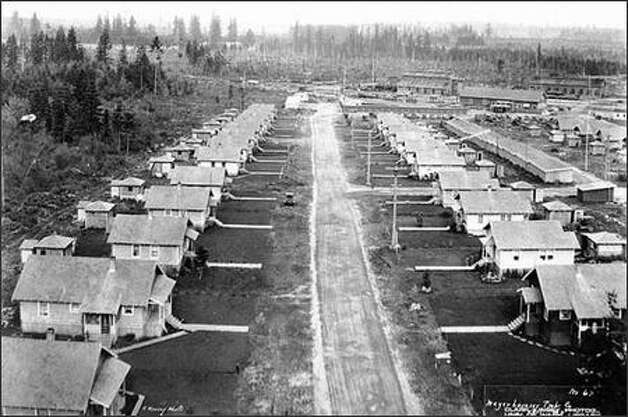

H.C. Frick Coke Company's town of Shoaf, the Shoaf Mine tipple and Coke Works are shown in the upper right hand corner. The Superintendent's house and Union Supply Company's Store are in the middle right of the photo.

Company towns solved a practical problem. The cotton kings and coal barons had to build towns because their vital resources—water and coal—were in out-of-the-way places. Motor and steel moguls had to build them because the working-class armies that were needed to manufacture their products grew faster than local governments could cope with. The most extraordinary company town of all, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was the creation of the government, rather than the private sector. A top-secret base, shielded from the rest of the world by barbed-wire fences and elaborate security checks, it housed a vast army of “Hillbilly girls” who did the grunt work involved in creating the atomic bomb.

Company towns usually came in one of two forms—the satanic and the Utopian. The satanic type were little better than gulags, where workers were forced to live in company shacks and spend their money in company shops. You could pass a lifetime in a company town without knowing any real freedom. But many other towns were monuments to the Utopian spirit. Benevolent bosses such as Milton Hershey, a chocolate king, and Henry Kaiser, a shipping magnate, went out of their way to provide their workers not just with decent houses but with schools, libraries and hospitals. This Utopian impulse inevitably went hand-in-hand with benevolent bossiness. Hershey served as his town's mayor, constable and fire chief and employed a squad of “moral police” to spy on the workers.

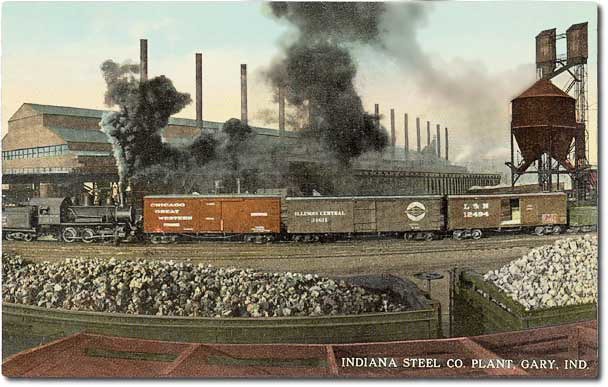

Over recent decades classic company towns have all but disappeared, destroyed by a combination of cars and global competition. Workers chose to live farther and farther away from their jobs. And even the most benevolent companies were forced to adopt a more ruthless attitude to their corporate assets. Some company towns have been reduced to tourist sites: Hershey attracts thousands of people a day with its tours and amusement park. Others have been transformed into post-industrial hells. Gary, Indiana, one of US Steel's proudest creations, now suffers from one of the highest murder rates in the country.

But company towns still shape American culture. Milton Hershey's paternalism survives in the form of a boarding school for orphans that sends 80% of its graduates to university. Henry Kaiser's survives in the form of Kaiser Permanente, one of America's best health-care systems. A handful of companies continue to support modern equivalents of company towns. IBM and PepsiCo have built town-sized company campuses in the middle of nowhere. Google and Microsoft have built huge cities to house their “server farms”. But neither corporate campuses nor server farms have the human dimension of classic company towns. (source: the Economist)

Hardy Green, former associate editor of BusinessWeek, explores the history of the American “company town.” From chocolate bar production in Hershey, Pennsylvania, to Maytag washing machines in Newtown, Iowa, the author examines how the production of one item in a town influenced the local and national economy and shaped the socio-political landscape of the respective locales. Mr. Green presents the two models that were often attributed to the management of the company town, the paternal model that fostered a sense of community, and what the author deems “Exploitationville,” in which the company was interested in producing profits without consideration for their employees. Hardy Green discussed his book at the New York Public Library’s Science, Industry, and Business Library in New York City.

This article is quite in-depth and gives a good overview of the topic. Thanks https://youractivityninja.com/online-dance-classes-for-kids

ReplyDelete