As reported by The New York Times Opinionator, "Life in the Swamp," by J. Brent Morris, on 19 October 2013 -- In early September 1863, a young Union soldier wrote a letter to his former professor back at Oberlin College, where he had studied before the war. The soldier, who identified himself only as “G,” had been tasked with taking a census of the freedmen on Craney Island, near Norfolk, Va. The African-American population of the area had been swelling since the arrival of Union forces the previous May, and soldiers like G were to provide the first step toward, among other things, organizing and recruiting black soldiers for the war effort.

As G related in his letter, the simple chore of tallying newcomers quickly transformed into a fascinating afternoon of storytelling when the soldier encountered two nondescript blacks, the 46-year-old Abraham Lester and his wife, Larinda.

After quickly noting his subjects’ names and ages, the student-soldier moved on to a more detailed set of queries, the answers of which, up until that point, had varied little among his respondents.

Abraham, however, piqued his interest with his answer to the first of these questions.

“How long have you been from home?,” the soldier asked. This was a variant on the question listed on G’s tally sheet, “How long have you been in our lines?” Other census takers had often encountered “contrabands” who did not fully understand what was meant by the question, and this simplified version assumed that their presence among Union troops dated from approximately the time they left “home” – that is, their former masters.

Without hesitation, Lester replied, “Four years.” This, however, predated the commencement of the war itself. G tried to clarify himself. “How long have you been with the Union Army?”

“Ever since they came to Suffolk,” Lester replied. “I was in the Dismal Swamp three years, and when I heard that the Army had come to Suffolk, I went to them, and have been with them ever since.”

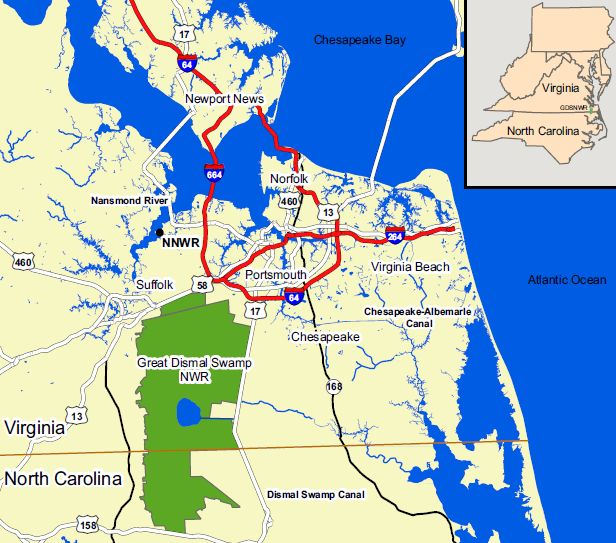

Abraham Lester had understood the question perfectly, and only slowly did G realize that the couple before him were maroons, fugitives who had fled slavery and precariously settled within the dark recesses of the Great Dismal Swamp, a wasteland spanning the Virginia-North Carolina border where few masters dared follow their fleeing bondsmen.

Hailing as he did from Oberlin, the soldier would have undoubtedly read about these maroons in one of the antislavery publications that circulated freely in that hotbed of abolitionism. But firsthand accounts of maroon life were nearly unheard of. In fact, Abraham Lester’s story is one of only a handful of known primary glimpses into the life of a maroon in the Great Dismal Swamp. It is one of even fewer that captures the merger of Dismal Swamp maroons’ century’s old fight to survive in the very midst of a plantation society with the larger fight for emancipation that was the American Civil War.

The Great Dismal Swamp was historically one of the most inhospitable tracts of land along the east coast of North America. Originally covering more than 1.3 million acres, very little of the swamp was above water. Here and there, dry ridges rose from the muck, providing precious solid ground that became the territory of numerous wild cattle, bears, deer and wolves. From the outside looking in, early Americans swore that the gases rising from the swamp were highly poisonous, that buzzards would not even fly over the quagmire, and that only suicidal fools dared venture in. Speculators contemplated draining the swamp but were largely unsuccessful. To most, the swamp seemed truly dismal — an eyesore, an obstacle, a quagmire.

Yet all the reasons white society gave for eschewing the swamp made it the perfect refuge for fugitives from slavery. The first self-emancipating slaves who sought the protection of the swamp in the late 17th century probably joined the remnants of long-defeated Native American groups who had sought the protection of the swamp much earlier. By the beginning of the 18th century, maroons of African descent were serving as military leaders of some of the burgeoning outlaw communities in regular raids on nearby plantations.

The considerable numbers of maroons who used the swamp as a base for these attacks, as well as those who settled in the innermost communities of the deep swamp, were constant thorns in the side of plantation society, both militarily and ideologically. Through trade, appropriation and their own ingenuity, maroons obtained or made weapons and developed remarkable skills as guerrilla fighters. Just as important, however, was their symbolic variance from the ideological foundations of American slavery: the notion that African-Americans could not survive without benevolent white supervision, that they did not truly desire their freedom and that they were pathetically inferior to the “master race” in every way. Rather, they challenged white authority and stood for centuries, unsubdued, as a powerful rebuke to the Slave Power.

When larger conflicts arose outside their swamp, Great Dismal maroons merged their own campaigns with those who would also make war on the people that enslaved them. Maroons in the Revolution, already loosely organized into war bands, served as guerrilla foragers for the British and as regular soldiers in Lord Dunmore’s Royal Ethiopian Regiment. Their own struggle for freedom spanned generations at that point, and it was bravely maintained until Union gunboats arrived in 1862 and the centuries-old fight again merged with another war against slaveholders. While the mass of the Union Army fought in Northern Virginia, former slaves, maroons and white Unionists undertook a guerrilla war to disrupt Confederate power in areas surrounding the swamp.

Many maroons who left the swamp to fight did not become regulars in the Union Army, but rather maintained their status as guerillas in the region. Dismal Swamp guerillas helped provision Union forces with beef and corn obtained in their plantation raids. Perhaps as important, dozens of maroons emerged from the swamp and served as scouts necessary for passage through the swamp. Moreover, maroon fighters already busy “spread[ing] terror over the land,” in the words of a North Carolina woman, loosely joined forces with the Confederate deserter Jack Fairless and his “Wingfield Buffaloes.” From their base on the North Carolina edge of the Great Dismal, guerrilla bands set off on regular campaigns into northeastern North Carolina, both to plunder and make good on their explicit pledge to “clear the country of every slave.”

So successful, in fact, were the maroons and other Buffaloes in commandeering supplies and helping to liberate bondsmen in the region that by mid-1863, a hastily organized local white “home guard” made desperate attempts to destroy their increasingly fortified base, or at least hit the guerrillas where it might hurt them the worst. Suggesting that they were aware of the crucial link between the maroons of the swamp and the guerrilla fighters, the home guard braved a direct assault on a deep-swamp maroon community, surprising the noncombatant group and killing many swampers in the process. Their attempts on the Buffalo base camp on the Chowan River were less successful. After initial forays in March failed to eject the Buffaloes, a larger force of partisan and regulars the next month found that the Buffaloes had dispersed back into the depths of the swamp ahead of the attack. All that greeted the frustrated Confederates was simple note pinned to a tree: “A leetle too late.”

The Carolinians must have already felt the truth of that note. Besides missing their guerrilla targets, by the fall of 1863 the Confederates were also rapidly losing ground in the region to Unionists. For the most part, the home guard had done a miserable job protecting the nominally pro-Confederate home front from Union-allied guerrillas. Indeed, the incompetence of the home guard only served to provoke further maroon reprisals on the civilian population.

In December 1863 Gen. Edward A. Wild led a raid through the swamp against white communities in North Carolina in December, but already that fall local residents were already declaring 1863 the “year of the black flag.” The Dismal Swamp counties in North Carolina passed resolutions addressed to the Confederacy formally withdrawing their support for the home guard and demanding they be officially recalled. The Buffalo’s adversaries would thereafter be no more than a dwindling clutch of vigilantes lacking even the support of a sympathetic civilian population. The Civil War thus came to an early end in the region around the southern Great Dismal Swamp.

Though some Buffaloes soon joined the fight at the Richmond front, others, like Abraham Lester, a maroon fighter and never an army regular, paused to enjoy something new but uncertain: liberty and the freedom to venture outside the protection of the Great Dismal Swamp. Toward the end of G.’s interview, Abraham’s wife, Larinda (whom he had met and wed in the swamp), joined the conversation, and it became clear that the war was perhaps the least of the worries that would burden now-former maroons like them. Still a bit skittish at the sight of whites after so many years in hiding, they would have to wrestle with uncertainties besides the still-ambiguous meaning of freedom: how to deal with a child that had never seen a white face, how to retrain one’s feet to tread upon solid dry ground, how to live alongside those who had once sent snarling bloodhounds into the swamp after their trail.

In September 1863, life outside the swamp offered an uncertain new world. The only certainties were the marks recorded in the young soldier’s notebook before he continued on with his census of the island: “Abraham Lester and Larinda White, Dismal Swamp, freedmen.” (source: The New York Times)

Need To Boost Your ClickBank Banner Commissions And Traffic?

ReplyDeleteBannerizer makes it easy for you to promote ClickBank products by banners, simply go to Bannerizer, and grab the banner codes for your favorite ClickBank products or use the Universal ClickBank Banner Rotator Tool to promote all of the available ClickBank products.

Wow, cool post. I'd like to write like this too - taking time and real hard work to make a great article... but I put things off too much and never seem to get started. Thanks though.

ReplyDeleteGet your cigarette at JohnDBlend

ReplyDeleteIn JohnDBlend We have

John D Blend

U2

Surya

Saat Mild

Canyon

LA

Luffman

Zon King

Impact

Visit our store to get your top 1 cigarette.