LABOR OF LOVE, LABOR OF SORROW

The New York Times, "The Family Came First," by Toni Morrison, published on 14 April 1985 -- AFTER slavery, when fresh-born blacks ceased to represent a supply of unpaid labor, agents of the law, the economy, the academy and the Government began to view the black family as problematic in every way. The education of black children, the employment of black adults, housing, medical care, food - whites suddenly began to regard these normal needs as insupportable burdens, and supposed solutions to ''the problem'' of the black family destroyed some families and disfigured others.

That blacks in America were able to maintain families at all and that these families endured after the Civil War is amazing. Perhaps because of this unexpected survival, historians usually treat the black family as a special phenomenon or trivialize it beyond recognition. Not so in ''Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow,'' Jacqueline Jones's perceptive, well-written study of black women in the labor force from slavery to the present.

Black Women, Work, and the Family From Slavery to the Present. By

Jacqueline Jones. Illustrated. 432 pp. New York: Basic Books

Placing the black family center stage in such a history as this is itself a singular idea, for which we owe the author gratitude. Miss Jones, who teaches history at Wellesley College, has made a valuable contribution to scholarship about black women on several counts. ''Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow'' exorcises several malignant stereotypes and stubborn myths, it is free of the sexism and racism it describes, and it interprets old data in new ways.

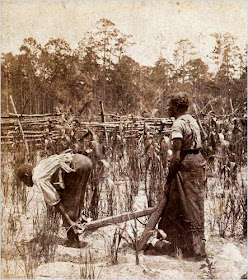

Miss Jones shows how the need to maintain family life shaped the work habits and choices of blacks in general and black women in particular. Examining black women as laborers is one thing; examining this labor force in the context of its life-and-death struggle to save the family is quite another. The attempt to annihilate black families was so spirited that every effort to protect those families was seen as nothing less than sabotage. A male slave who ducked off the plantation to go fishing was perceived as a loafer rather than a provider. Similarly, after slavery, when free black women stayed at home to care for their children (a duty and virtue for white women), they were said to be ''doing nothing'' and to have ''played the lady'' by demanding that their husbands ''support them in idleness.''

Like a silent, underground river, family priorities run through the work choices blacks made after and during slavery. ''Freed blacks resisted both the northern work ethic and the southern system of neoslavery,'' Miss Jones writes. ''The full import of their preference for family sharecropping over gang labor becomes apparent when viewed in a national context. The industrial North was increasingly coming to rely on workers who had yielded to employers all authority over their working conditions. In contrast, sharecropping husbands and wives retained a minimal amount of control over their own productive energies and those of their children on both a daily and seasonal basis. Furthermore, the sharecropping system enabled mothers to divide their time between field and housework in a way that reflected a family's needs. The system also removed wives and daughters from the menacing reach of white supervisors. Here were tangible benefits of freedom that could not be reckoned in financial terms.''

Though slave women are stereotypically thought of as house servants, 95 percent of them were fieldworkers who had the same workload as men. And contrary to the notion that black women during slavery regarded kitchen work as a ''promotion'' from fieldwork, most sought the latter to be farther away from white supervision and closer to their own families. Deliberate ineptitude in the kitchen seems to have been the easiest route out of the big house. And this maneuver was echoed in the refusal of black domestics to ''live in'' when they reached the city.

Of signal importance is that blacks often decided to migrate to urban centers to get better education for their children - a priority equal to (if not greater than) the hope of more and better work. Another manifestation of the priority of the family is that blacks repeatedly chose collectivism based on kinship over ''individualistic opportunity.'' Miss Jones does justice to this seldom recognized characteristic of black people and suggests that this collectivism accounts for the rapid spread of black protest in the 1960's.

Once again the myth of the emasculating black matriarch is deftly punctured here. Miss Jones supplies more evidence (there seems never to be enough to get rid of the myth) showing that during and after slavery black women were not the lone protectors of their families and black men traditionally risked their lives trying to defend their wives and children. The author's refusal to assert female competence at the expense of male roles is refreshing.

Historians usually speak of white women as though they primarily supported black causes. Other than Miss Jones, few writers have mentioned that white women could be as racist as their men. Appropriately, Miss Jones distinguishes the kind of white women who cried ''Lynch her!'' to black schoolgirls in Little Rock, Ark., from those who worked hard on black causes.

Rather than simply looking at data, Miss Jones sees them. In so doing, she has turned an arc light on several dark and unexplored corners. There is a marvelous passage on dressing up - how important ribbons, hats, shoes and colorful dresses were to impoverished black women. Films, plays, newspaper cartoons and advertisements once joked about the way black women dressed up, and white women sometimes felt outrage at, and contempt for, black women's choices of fashion. In the mid-1860's, in Wilmington, N.C., Miss Jones writes, quoting an observer, white women took ''great offense'' at black women's wearing veils and gave up the style altogether.

The book contains a surprising analysis of how Ebony magazine - a magazine dominated by men at its inception - encouraged black women by closely chronicling their accomplishments. There is a discussion that links the way black women nourished the civil rights movement with the way they protected and encouraged runaway slaves. Feeding runaways with provisions stolen from the mistress's pantry during slavery grew into giving banquets for civil rights activists during the 1960's. Spirituals sung in clandestine slave services became rallying songs at protest meetings.

THOUGH she provides a context for joining the African past to the Afro-American present, Miss Jones is not at all optimistic about the future. She believes that the black woman's unprecedented strength can no longer ward off the quite precedented assaults on the black family. But in calling for ''a massive public works program (and) a 'solidarity wage' to narrow the gap between the pay scales of lower- and upper-echelon workers,'' she is exchanging one dependency for another. If Miss Jones is right, if the traditional ''make a way out of no way'' resourcefulness of black women can't save the black family and blacks are still at the Government's mercy, then they face their gravest danger yet.

Fully half this book is devoted to strategies slaves and newly freed women used to balance labor with family. As well done as it is, this section is the luxury we pay for by having less of Miss Jones's scholarship about events of the 1970's and 80's. The sections of the book that deal with more recent history merely track events without offering insights into them. Perhaps a separate text is needed to tell us exactly how, among modern blacks, the expression ''Hey, mama'' took on sexual connotations; how marriage came to be perceived as a barrier to self-fulfillment; and how black children came to be viewed as the Typhoid Marys of poverty rather than the victims they in fact are. Such an analysis is outside the scope of this book but not beyond Miss Jones's gifts. (source:The New York Times)

Considering to join more affiliate networks?

ReplyDeleteVisit this affiliate directory to see the ultimate list of affiliate networks.