As reported by the UK Guardian, "The hidden holocaust: Was Belgium's King Leopold II a mass murderer on a par with Hitler or a greedy despot who turned a blind eye to a few excesses? A new book has ignited a furious row in a country coming to grips with its colonial legacy," Stephen Bates reports on 12 May 1999 -- As the sun sank slowly over Brussels, its fading rays glinted off the glass domes and towers of the magnificent Victorian greenhouses in the grounds of the royal palace at Laeken. Built to celebrate King Leopold II's acquisition of the Congo a century ago, the greenhouses stretch for more than half a mile and are among the most visible and grandiose remaining symbols of a once enormous African empire, 60 times the size of Belgium. The colony was the largest private estate ever acquired by a single man - and one he never saw.

It is said that when he showed his nephew the greenhouses, the youth gasped that they were like a little Versailles. 'Little?' snorted the king.

Leopold always did think big. But the row over the king's notorious stewardship of his African territories still has the ability to evoke raw emotions in a country trying to come to terms with a brutal colonial past.

The question is: was the spade-bearded old reprobate a mass-murderer, the first genocidalist of modern times, responsible for the death of more Africans than the Nazis killed Jews? Was his equatorial empire, the setting for Conrad's Heart of Darkness and the terrible Kurtz with the human heads dangling round his garden, the scene of a largely forgotten holocaust? The old wounds have been re-opened by the publication of a book called King Leopold's Ghost, by the American author Adam Hochschild, which has brought howls of rage from Belgium's ageing colonials and some professional historians even as it has climbed the country's best-seller lists.

Alice Seeley Harris, Manacled members of a chain gang at Bauliri. A common punishment for not paying taxes, Congo Free State, c. 1904. Courtesy Anti-Slavery International / Autograph ABP

The debate over Belgium's colonial legacy could not be more timely. In the realm beyond the palace walls where Leopold's great grandson Albert II is now king, the openly racist extreme rightwing Vlaams Blok, which blames much of the country's ills on coloured immigrants from Africa, is bidding to become one of the biggest parties in next month's elections.

And the planes which soar over the greenhouses as they depart Brussels sometimes carry human cargo - black asylum seekers being unceremoniously deported, occasionally naked and still bleeding, back to Africa. Last September, the Belgian immigration service succeeded in suffocating one of them, a Nigerian woman called Semira Adamu, 20, on board the plane that was to take her home, by shoving her head under a pillow. The police videoed themselves chatting and laughing while they pushed her head down. It took them 20 minutes to kill her.

The history of Leopold's rule over the Congo has long been known. It was first exposed by American and British writers and campaigners at the turn of the century - publicity which eventually forced the king to hand the country which had been his private fiefdom over to Belgium.

But Hochschild's book has hit a raw nerve for a new generation with its vividly drawn picture of a voracious king anxious to maximise his earnings from the proceeds of rubber and ivory.

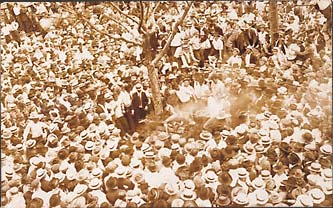

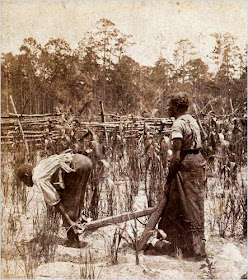

It is clear that many of Leopold's officials in the depots up the Congo river terrorised the local inhabitants, forcing them to work under the threat of having their hands and feet - or those of their children - cut off. Women were raped, men were executed and villages were burned in pursuit of profit for the king.

But what has stuck in the gut of Belgian historians is Hochschild's claim that 10 million people may have died in a forgotten holocaust. In outrage, the now ageing Belgian officials who worked in the Congo in later years have taken to the internet with a 10-page message claiming that maybe only half a dozen people had their hands chopped off, and that even that was done by native troops.

They argue that American and British writers have highlighted the Congo to distract attention from the contemporary massacre of the North American Indians and the Boer War.

Under the headline 'a scandalous book', members of the Royal Belgian Union for Overseas Territories claim: 'There is nothing that could compare with the horrors of Hitler and Stalin, or the deliberate massacres of the Indian, Tasmanian and Aboriginal populations. A black legend has been created by polemicists and British and American journalists feeding off the imaginations of novelists and the re-writers of history.' Professor Jean Stengers, a leading historian of the period, says: 'Terrible things happened, but Hochschild is exaggerating. It is absurd to say so many millions died. I don't attach so much significance to his book. In two or three years' time, it will be forgotten.' Leopold's British biographer, Barbara Emerson, agrees: 'I think it is a very shoddy piece of work. Leopold did not start genocide. He was greedy for money and chose not to interest himself when things got out of control. Part of Belgian society is still very defensive. People with Congo connections say we were not so awful as that, we reformed the Congo and had a decent administration there.' Stengers acknowledges that the population of the Congo shrank dramatically in the 30 years after Leopold took over, though exact figures are hard to establish since no one knows how many inhabited the vast jungles in the 1880s.

It is true too that some of those reporting scandals had their own knives to grind. Some were Protestant missionaries who were rivals to Belgian Catholics in the region.

Yet Leopold certainly emerges as an unattractive figure, described as a young man by his cousin Queen Victoria as an 'unfit, idle and unpromising an heir apparent as ever was known' and by Disraeli as having 'such a nose as a young prince has in a fairy tale, who has been banned by a malignant fairy.' As king, he did not bother to deny charges in a London court that he had sex with child prostitutes. When the bishop of Ostend told him that people were saying he had a mistress, he is reputed to have replied benignly: 'People tell me the same about you, your Grace. But of course I choose not to believe them.' His wiliness in convincing the world that he had only humanitarian motives in annexing the Congo, in persuading the Belgian government essentially to pay for his purchase and in buying up journalists, including the great explorer Henry Morton Stanley, to promote his cause show both cunning and skill.

Henry Morton Stanley

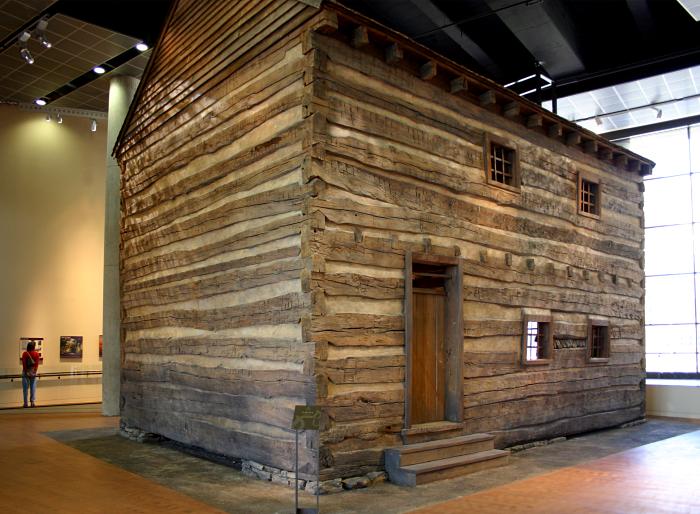

Emerson claims Leopold was appalled to hear about the atrocities in his domain, but dug his heels in when he was attacked in the foreign press. He did indeed apparently write to his secretary of state: 'These horrors must end or I will retire from the Congo. I will not be splattered with blood and mud: it is essential that any abuses cease.' But the man who (as Queen Victoria said) had the habit of saying 'disagreeable things to people' was also reputed to have snorted: 'Cut off hands - that's idiotic. I'd cut off all the rest of them, but not hands. That's the one thing I need in the Congo.' Although few now defend him, strange things happen even today when the Congo record is challenged. Currently circulating on the internet is an anguished claim by a student in Brussels called Joseph Mbeka alleging he his thesis marked a failure when he cited Hochschild's book: 'My director turned his back on me.' Daniel Vangroenweghe, a Belgian anthropologist who also published a critical book about the period 15 years ago, says: 'Senior people tried to get me sacked at the time. Questions were asked in parliament and my work was subjected to an official inspection.' At a large chateau outside Brussels in Tervuren is the Musee Royal de l'Afrique, which Leopold was eventually shamed into setting up to prove his philanthropic credentials. It contains the largest African ethnographic collection in the world, rooms full of stuffed animals and artefacts including shields, spears, deities, drums and masks, a 60ft-long war canoe, even Stanley's leather suitcase.

There is one small watercolour of a native being flogged, but a visitor would be hard-pressed to spot any other reference to the dark side of Leopold's regime. Dust hangs over the place. A curator has said changes are under consideration 'but absolutely not because of the recent disreputable book by an American'.

The real legacy of Leopold and of the Belgians who ran the country until they were bloodily booted out in 1960 has been the chaos in the region ever since and a rapacity among rulers such as Mobutu Sese Seko which outstripped even the king's. Leopold made £3m in 10 years between 1896 and 1906, Mobutu filched at least £3bn. When the Belgians left there were only three Africans in managerial positions in the Congo's administration and fewer than 30 graduates in the entire country.

Vangroenweghe says: 'Talk of whether Leopold killed 10 million people or five million is beside the point, it was still too many.' I asked Belgium's prime minister, Jean-Luc Dehaene, about the Congo legacy this week. 'The colonial past is completely past,' he said. 'There is really no strong emotional link any more. It does not move the people. It's part of the past. It's history.' (source: The UK Guardian)