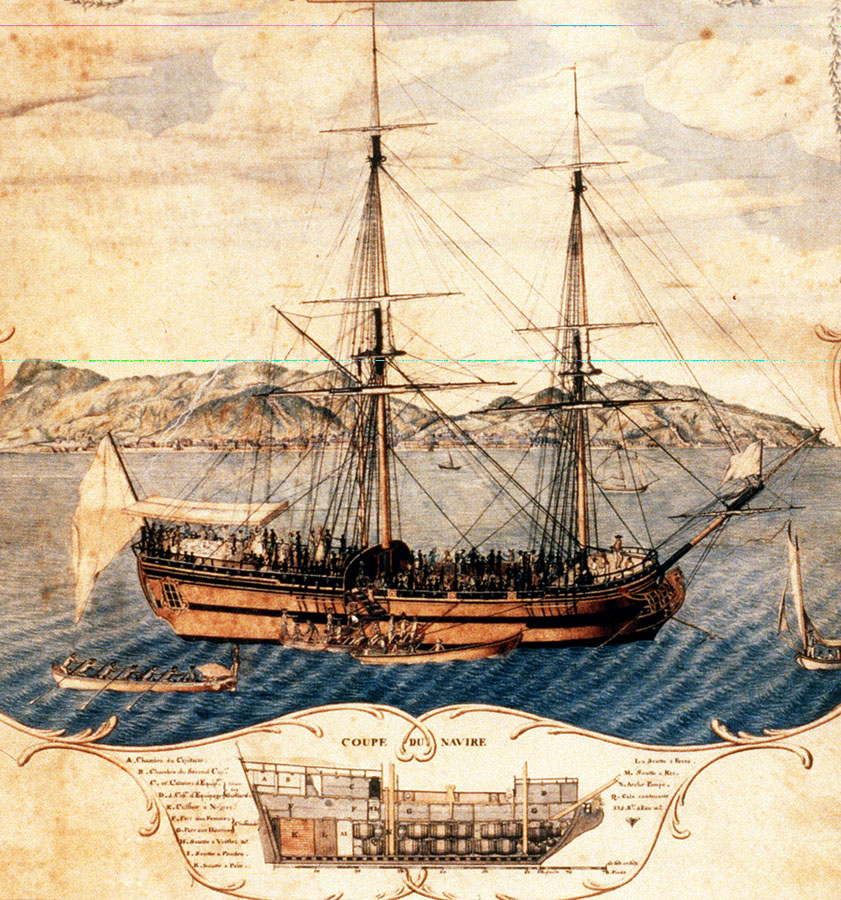

From the London Review of Books, "Tricky Business," Megan Vaughan reviews The Diligent: A Voyage through the Worlds of the Slave Trade by Robert Harms, Perseus, 466 pp, £17.99, February 2002, ISBN 1 903985 18 8 -- On 1 June 1731, the Billy brothers, Guillaume and François, waved goodbye to their ship, the Diligent, as it set sail from Brittany. It was weighed down with Indian cloth, cowry shells from the Maldives, white linen from Hamburg, guns, ammunition and smoking pipes from Holland, kegs of brandy from the Loire Valley, and with the all-important supplies for the crew: firewood and flour, dry biscuits, fava beans, hams, salt beef, cheese, white wine and water. There was one other item to be loaded: 150 slave irons with their locks and keys, manufactured by the Taquet brothers in Nantes. Each iron could restrain two slaves. The Diligent was setting off on its first slave-trading voyage.

The Africans who would wear these irons were destined for the French West Indian island of Martinique. French development of this and other islands had lagged behind the English. In 1700 there were about thirty thousand African slaves in the French colonies, compared with around a hundred thousand in the English ones, and sugar exports were correspondingly smaller, but the first decades of the 18th century would see a rapid growth in French involvement in the slave trade and in the development of their colonies. The activities of the Billy brothers were part of a more general trend, as the usually dirigiste French Crown gave a greater degree of freedom to merchants and entrepreneurs.

The 1731 voyage was the Billy brothers’ first involvement in the slave trade. It demanded a very significant investment: the cost of sending a ship on the African slave run was two or three times that of other branches of commerce. Outfitting the Diligent, including food, loading costs and two months’ salary for the crew, came to 80,000 livres – more than four times the price of the ship itself, and this before insurance. The Billy brothers were expecting big profits from the sale of Africans they would never see.

Robert Harms has based his riveting account of the ‘worlds of the slave trade’ on a journal kept by a young lieutenant on the Diligent, Robert Durand, a document sold in the 1980s to the Beinecke Library at Yale, where Harms teaches. Historians have uncovered records of more than seventeen thousand slaving voyages in the 18th century, but, as Harms points out, only a handful give us any insight into the daily life of the ship, the crew and its human cargo. Most are careful records of the ship’s passage, prices, rates of exchange, slaves’ vital statistics and deaths. As Robin Blackburn has argued, the slave trade and the slave plantation were run with an instrumental rationality, according to business principles that were ahead of their time, and produced an abundance of statistics. Durand’s journal is one of the handful of records that provides more than this, but even so it is characterised as much by its silences as by its evocative descriptions and jaunty drawings. ‘Curiously,’ Harms writes, ‘Robert Durand mentioned the African captives only twice during the entire 66 days of the middle passage, and then only to record deaths.’

Harms uses the voyage of the Diligent to take us through the ‘worlds’ of the Atlantic slave trade in the early 18th century. There are three of them in this case: France, West Africa and Martinique, with a few offshore islands thrown in. Harms’s argument is that these worlds are distinct, with their own histories and dynamics, but that during this period the slave trade was beginning to link their fates. Perhaps his most original contribution to the ever increasing scholarship on slavery, however, is his account of the French slave traders and the political and social context of early 18th-century French colonial commerce.

The ships that sailed from Brittany had their backs turned to the impoverished rural economy of the hinterland. The big players in colonial trade were Nantes and later Lorient, and though government-chartered companies had previously exercised near complete monopolies, by this time the merchants of Nantes were proving successful advocates of private enterprise. The development of the French colonies may have been dirigiste in comparison to the English, but the French King could not afford to ignore an increasingly vociferous group of private merchants pressing for reform of the now discredited system of corporate mercantilism. Still, French colonial trade, as Harms makes clear, was relatively unintegrated into the larger economy, which was still predominantly agricultural. In the 18th century, commercial cities like Nantes were a bit like the ‘free trade zones’ of the ‘Third World’ today – disconnected from the rest of the country, importing and exporting goods that most people would never own, and perhaps never see. Arriving in Nantes, with its grand merchants’ mansions and its opera house, the English traveller Arthur Young found himself in a strikingly different world from the one he had been journeying through: ‘Mon Dieu! I cried to myself, do all the wastes, the deserts, the heath, ling, furz, broom and bog that I have passed for three hundred miles lead to this spectacle? What a miracle, that all this splendour and wealth of the cities of France should be so unconnected with the country!’ (source: The London Review of Books: Vol. 24 No. 24 · 12 December 2002, pages 23-24 | 3741 words)

تنظيف موكيت بالدمام

ReplyDeleteشركة تنظيف موكيت بالدمام

شركة مكافحة حشرات بالدمام

شركة تنظيف فلل بالدمام

شركة صيانة مكيفات بالخبر

شركة كشف تسربات المياه بالاحساء

شركة تنظيف بيوت بالدمام

شركة نظافة بالدمام

شركة تنظيف منازل بالدمام

شركة تنظيف منازل بالدمام

شركة تنظيف شقق بالدمام

شركة مكافحة حشرات بالظهران