From the Washington Post, "Students Trace University of Maryland's Slavery Ties," by Jenna Johnson a Washington Post Staff Writer, on 10 October 2009 -- When the University of Maryland elaborately celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2006, there were only fleeting mentions of its early ties to slavery. The next year, black faculty members urged President C.D. Mote Jr. to follow the lead of Maryland lawmakers and issue an apology for the university's historic use of slave labor.

Mote refused to do so, but he asked a group of students to research the topic. As they presented him with a final report Friday, the students recommended the university "issue a statement of regret," honor African Americans who assisted with its creation by naming them founders, add classes focused on slavery, continue research and ensure that the university is not benefiting from current international "coercive labor practices."

Mote said Friday that he will review the recommendations but that he has no plans for a statement because all institutions at that time were influenced by slavery.

"It's a little difficult for a university to retrospectively change its founders," he said. "It's like changing the signers of the Declaration of Independence."

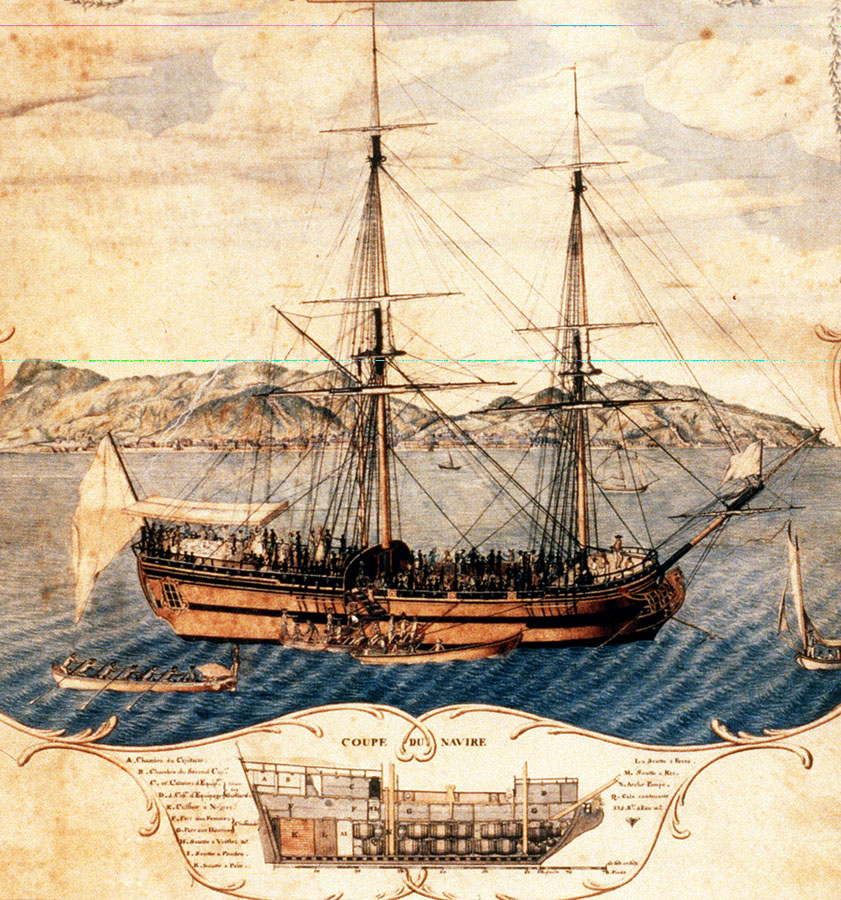

The report does not contain a "smoking gun" or examples of how slaves were forced to construct parts of the campus beginning in 1856, just before the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, said history professor Ira Berlin, who led the class. But at least 16 of the university's original 24 trustees owned slaves, and it would have been nearly impossible then to "undertake this type of enterprise in Maryland and not use slaves," he said.

"If slaves didn't lay the bricks, they made the bricks. If they didn't make the bricks, they drove the wagon that brought the bricks. If they didn't drive the wagon, they built the wagon wheels," Berlin is quoted as saying in the report.

The report tells the story of three men who were instrumental in opening the Maryland Agriculture College, as the university was then known, at a time when farmers were forced to plan how they would operate in a post-slavery economy.

The three "founders" profiled are remarkably different: Charles B. Calvert, a principal founder and wealthy backer of the school, came from a prominent Maryland family that had owned dozens of slaves for decades. Benjamin Hallowell, the school's first president who resigned after one month, was a Quaker who adamantly opposed slavery and requested that slave labor not be used. Adam Plummer was one of Calvert's slaves, whose labor "created the wealth that funded the college," the students wrote in the report.

Plummer's great-great-grandson, the Rev. L. Jerome Fowler, said he received a copy of the report this week and opened to the table of contents. Tears came to his eyes.

"I saw my ancestor, Adam Francis Plummer, listed as a founder," Fowler said at a reception Friday. "You don't know what that did for me."

In the past decade, several other universities have researched the role of slavery in their construction and early days of operation. But in many instances, these research projects are conducted by professors and historians, not undergraduates, Berlin said. During the first semester, the class studied the history of slavery. The next semester, they began researching and writing.

"To be able to rummage through archives and decipher old handwriting -- undergraduates never get to do that," said Jessica Dwyer-Moss, a senior majoring in government, politics and history. Unlike class reports that are graded and forgotten, Dwyer-Moss says, she hopes this report is read throughout the campus so that it "might do some good in the world." (source: Washington Post)

Slavery and the University of Maryland (Fortune's Bones, February 24, 2012) from The Clarice on Vimeo.