According to an article from Southern Changes Magazine (Volume 3, Number 1, 1980), entitled "A Defeated Herman Talmadge and the Black Vote," by Betty Norwood Chaney and Steve Suitts -- Because no one before or since his death is remembered by Blacks with as much reverence as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., his ideals have become the political yardsticks by which the activity of others is measured. Every election year in Atlanta conflicts crop up between Coretta Scott King, wife of the slain leader, and some other Black leadership—often the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the organization he founded—over who measures the candidates most accurately by Dr. King's standards.

This campaign year was no exception. In late October, SCLC's former president and executive director, Ralph Abernathy and Hosea Williams, endorsed Ronald Reagan for president, to the horror of many Black leaders. Ms. King was shocked and reminded the public that her husband once called Reagan a second-rate actor and a warmonger. Williams retorted that if the Carter administration had given him as much federal money as it had supplied Ms. King's non-profit center he also might have supported Carter.

While spotlighted nationally, this crack in Black leadership was a slight tremor when compared to the split that graphically was played out in Georgia's senatorial campaign with U.S. Senator Herman Talmadge. In fact, the senate race may have been the clearest example of what has happened to King's vision of Blacks in Southern politics.

Back in the summer, Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, known for his oratory, endorsed Lt. Gov. Zell Miller for the U.S. Senate, making the statement that any Black voters who supported incumbent Herman Talmadge "might as well walk down Auburn Avenue and spit on King's grave." Talmadge, who was denounced by the Senate in October 1979 for reprehensible conduct that "tends to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute," has long been considered a staunch segregationist by many. "All that King fought for was opposed by Herman Talmadge and is opposed by Herman Talmadge," Jackson said, with the agreement of others such as Julian Bond. Talmadge never supported one piece of civil rights legislation in his 23 years in the Senate.

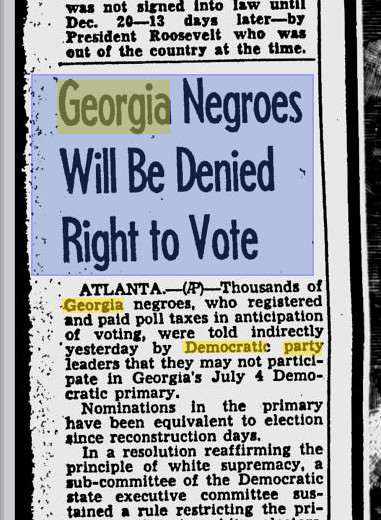

Talmadge, whose election as governor back in 1948 was considered the "No. 1 job of all Georgia Klansmen," has been referred to as "Klan loving 'Hummon' Talmadge." One of the laws he signed as governor required every voter in the state to "re-register," in an attempt to reduce the number of Blacks registered to vote.

Talmadge's positions on human rights are clearly worse than Miller's. Miller supports the extension of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Talmadge has voted against the original bill and its extension. Miller worked to pass the Georgia Fair Employment Practices Act, which makes discrimination in employment illegal, while in 1955 Talmadge wrote that the establishment of the Federal Employment Practices Commission "would steal away our birthright of freedom and put all of us at the complete mercy of such organizations as the NAACP." Miller supports affirmative action programs which attempt to correct past injustices. On June 28, 1977, Talmadge voted against the use of federal funds to administer affirmative action programs in hiring, promotions and school admissions.

Georgia House Speaker Tom Murphy (2nd from right) with (left to right) Mrs. Alveda King Beal (state rep. 28th Dist.), Rev. Martin L. King Senior, Dr. Benjamin Mayes, and Coretta Scott King.

A few days after Jackson's statement, however, State Rep. Alveda King Beal, granddaughter of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr., now in her first term as a state legislator from Atlanta, announced her support of Herman Talmadge. In a prepared statement she said, "People may ask why I'm endorsing Sen. Talmadge. I ask why not. For those who say Herman Talmadge fought against civil rights, I say he had a lot of company...We must believe that men can change. I believe in change. Today Herman Talmadge is fighting for all Georgians, Black and White."

In thanking Beal for her support, Talmadge referred to the fact that he was a close and personal friend of her grandfather, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr. The senior King did have kind words to say about the senator throughout most of the campaign, but had always stopped short of endorsing him. Then in a surprise move, during the weekend before the primary, King lined up with 50 to 60 other Black ministers in Atlanta in support of Zell Miller. He offered a motion that the group back Miller and promote his candidacy from their pulpits on Sunday morning. The motion passed unanimously.

King was unavailable for comment later that day. Then the very next day in Savannah he urged Black churchgoers there to "follow the leadership," referring to a group of ministers who had lined up with Talmadge.

King finally declared he would not endorse anybody. He told the Savannah group he could only "suggest" that they follow the leadership of the pastors and ministers who were trying to do the best for them.

In the meantime, Coretta King thought that she had better clarify her position amid all the confusion and announced her support of Miller. However, another respected Black leader, Jesse Hill, president of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, a member of the King Center board, and former Atlanta Chamber of Commerce president, barely stopped short of an endorsement of Talmadge. Days before the election Hill held a news conference for the sole purpose of offering high words of praise for Talmadge, calling him "one of the most effective, hard-working senators serving us in the United States Senate."

Some other Black leaders across the state were more direct. For example, one of the first Black elected officials of Dawson, Georgia, Robert Albritten, distributed a letter endorsing Talmadge, citing the funds the senator had helped secure for Black colleges and his influential position in Congress.

Thus, what at the outset appeared a clear choice for Black voters in Georgia's 1980 senatorial election—a choice between the son of Eugene Talmadge, the state's most notorious racist, who had grown up to be called a friend of the Klan and author of a well-known treatise endorsing segregation, and a host of other contenders, one considered a liberal—was anything but that.

The election returns showed signs of the Talmadge Black support. Although Miller was able to secure nearly 25 percent of the total vote in the first primary and forced the veteran senator into a runoff for the first time in his 30-year political career, Talmadge came back to claim a resounding victory over Miller with almost 60 percent of the vote. Miller's campaign had been banking on a heavy turnout of Black voters to overtake Talmadge in the runoff. An examination of 14 predominantly Black precincts around Atlanta following the election showed only 25.9 percent of the electorate voted in the runoff election whereas the statewide turnout of all voters was over 40 percent. Moreover, from 20 to 25 percent of the Black precincts voted for Herman Talmadge. In short, the incumbent won with noticeable Black support.

When Zell Miller conceded the Democratic primary and went off to the local theater to see a Willie Nelson film he had missed while campaigning, Mack Mattingly reminded the Georgia press that he was the Republican challenger. Not impressed, Senator Talmadge refused an invitation to debate and went on back to Washington after thanking his friends and supporters for their victory. Mattingly, who lived on the Georgia coast, had never held public office. He had run a small campaign in an unsuccessful bid for a congressional seat earlier but had earned little public recognition and not many votes.

The Republican campaign had begun earlier in the summer when Mattingly became the party's nominee in a primary where less than 100,000 Republicans voted. Handsome and energetic, Mattingly traveled the state walking the cafes of small south Georgia county seats and competing with grocery handbills in Atlanta suburban shopping centers.

As November approached, Talmadge began considering his opponent more seriously. He gathered his colleague from the Senate, Sam Nunn, and Governor George Busbee as cheerleaders for his campaign. He also once again activated without fanfare his efforts with Black leaders who had supported him in the primary.

Mattingly did not court the Black vote perhaps because his contacts and association with Black leaders across the state and in Atlanta could be counted on one hand. He did appear at a political forum at predominantly Black Atlanta University but, under questioning from students, had difficulty identifying exactly which country was Zimbabwe. Before an older crowd of Black businessmen and preachers at Atlanta's Hungry Club, Mattingly admitted his performance at Atlanta University had not been his best and assured the audience that he was sensitive and concerned about their problems.

The campaign ended with a flurry of television ads by both candidates. Mattingly's spots hammered away at Talmadge's poor attendance during important votes in Washington while Talmadge reminded people of his accomplishments for Georgia in the last three decades. Black leaders throughout the state did not become visible in the campaign and were concentrating on the presidential race where many responded to the Abernathy-Williams endorsement of Ronald Reagan.

By early evening November 4, as votes came in to the Talmadge headquarters where Alveda King Beal and others gathered to celebrate Talmadge's victory, wire services and television networks quickly projected a victory for the senior senator. From the earliest moment, Talmadge himself was more cautious and would say for the TV cameras only that "I want to see some arithmetic."

And so he should. By 10:30 on the morning of November 5 after the Talmadge campaign had declared victory, the Atlanta Journal contradicted its sister morning paper, the Constitution, with bold two-inch headlines: MATTINGLY WINS. Georgia's preeminent politician had lost to a Republican who only six months earlier was unknown to probably 99.9 percent of the Georgia public.

The voting returns in the general election are an apparent contradiction of the Democratic primary in urban and suburban areas. Among the 10 metropolitan counties in Georgia in the Democratic primary Talmadge won seven and received no less than 40 percent of the vote in the remaining three. In the general election, Talmadge won only two of the 10 counties (see Chart #1).

For example, Talmadge carried Cobb County, bordering Atlanta on the northwest, with about 54 percent of the vote, against Lt. Gov. Miller. Against Mattingly, Talmadge picked up less than 30 percent of the vote.

The voting within Atlanta followed the same contradictory pattern. Almost every precinct which Talmadge carried in the Democratic primary, he lost in the general election; moreover, the predominantly Black precincts in the city switched from majority opposition to majority support for Talmadge. The majority White precincts in the city flipped the other way: from majority support to majority opposition of Talmadge (see Chart #2).

The Black support for Talmadge on November 4 was not without some defection across the board in almost every precinct. For example, while Miller carried the Black precinct at Collier Heights School in Atlanta by 78 percent, the flip gave Talmadge only about 64 percent of the vote in his race against Mattingly.

In south and middle Georgia counties outside the metropolitan area, Talmadge maintained much of the same White support against Mattingly as he had had against Miller. Indications are, however, that in many of the largely Black populated counties, voters also reversed from primarily opposing Talmadge in the Democratic run-off to supporting him in the general election.

Although some north Georgia counties deserted the Talmadge column on November 4 after giving him a majority in the Democratic run-off, the Black voters were probably the only ones who, as a group, actually voted against Talmadge in the run-off and two months later went back to the polls and voted for him in the general election. Georgia's voter turnout in the two-party contest was almost twice that of the run-off. In the metropolitan areas which Talmadge lost to Mattingly, the increases were mammoth. In Cobb County two-anda-half times more than the 40,000 voters in the Democratic run-off came out to vote in the general election. These new voters—suburban, predominantly White —chose Mattingly in overwhelming numbers.

In the White urban precincts of Atlanta the turnout also increased—by a little less than twice as much as the run-off—and most of these new voters probably favored Mattingly. In these precincts Talmadge actually received a few less votes than he did in the run-off with the lower voter turnout. At Christ the King Church in a White section of Atlanta, Talmadge received 366 of the 608 votes in the Democratic run-off but only 281 votes of the total 1,121 in the general election.

Black precincts also increased their turnout although not in numbers like the suburbs. Yet, even if all the new Black voters who came out only in the general election had supported Talmadge, some Blacks who voted in both elections had to flip-flop for Talmadge. Blacks more than any other group tried to save Talmadge by changing their vote.

The supreme irony of Herman Talmadge's defeat has to be the fact that, more than anyone else, Black voters tried to save him. While the Black precincts gave Talmadge almost one in five votes against Miller in the Democratic run-off, they provided Talmadge with his strongest support, about 70 percent of their vote, in the general election.

In the race against Miller, Talmadge's support in the Black community is said to have come from the power of incumbency and seniority.

Some political observers believe that the political IOU's of Talmadge's 30 years of service in Georgia allowed him to collect the Black support he received. His assistance, for instance, in helping the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Social Change obtain federal funding probably did have something to do with the King family's vacillation. (Since the Democratic primary the property surrounding the King Center has been designated a national historic park by Congress.) Also, because of his support for Morris Brown College, the AME ministers who run the school gave him the Man of the Year Award and their endorsement.

There are other examples. Talmadge interceded on behalf of the Wheat Street Baptist Church with HUD on problems they were having with a highrise for the elderly. "I have met a lot of White politicians who say they are for equal rights, but then they fail to deliver when it comes to equal opportunity. Herman Talmadge has delivered. He has never hesitated to use his seniority and his influence in fighting for minority business development," says the Rev. William Holmes Borders, pastor of Wheat Street Baptist Church and a veteran civil rights advocate. Borders is highly esteemed in the Black community and when he says that "Herman Talmadge has delivered," it becomes gospel to a large number of people.

...

Evelyn Broadus, a former employee of Zell Miller, was a paid staff member at Talmadge's Atlanta headquarters. Her decision to support Talmadge over Miller was due to no shortcoming on the lieutenant governor's part, she said, but simply because she felt we needed someone with seniority. "He has been in office and he knows how to get his way," she said. Betty Stevens, a counselor with the Atlanta Board of Education, agreed. "It's just common sense," she said. "It takes experience and seniority to be effective. Talmadge has shown he has some clout."

Stevens, however, like several other Blacks interviewed, also expressed a dislike for Miller. "If the only bad thing people can say about Talmadge is that back in 1945 or so he was a segregationist, well, it hasn't been 15 years ago since Zell Miller was Lester Maddox's right-hand man. Miller was executive secretary to Maddox during the former governor's term of office. Maddox was elected governor after his segregationist stands were widely publicized."

Savannah Alderman Roy Jackson voiced a similar opinion: "Some say that Talmadge was a segregationist leader 25 years ago," Jackson said. "I say he had a lot of company. The leader of the pack was Zig-zag Zell, who we are being asked to vote for on the basis that he is not a segregationist. Zig-zag Zell kept Gov. Lester Maddox's office while Maddox was away making axe handles."

He went on to question, "If Zig-zag Zell is not a racist, why did he call Martin Luther King a communist? If Zell Miller is a great friend of the Black and poor people, why in his 1968 campaign for Congress did he say all the federal funds being used to help the Black and poor people should be used to investigate communist infiltration of the NAACP?"

These sentiments may have played a part in the general election. Probably more certain, Blacks in Georgia voted a straight Democratic ticket on November 4 and Talmadge was in that column. In addition, Mattingly was an unknown candidate who had no public record of sensitivity to Blacks and was a member of the party of Ronald Reagan whom Georgia Blacks rejected in overwhelming percentages at the polls.

By any arithmetic, the voting returns in the Senate race show that Black voters lost. Their candidates lost because their choices were muddled by divisions among Black political leadership during the Democratic primary and because in the general election they had no where else to go than to Talmadge. Black voters also lost because there never was an opportunity to coalesce with White voters on any of the candidates. When the Black voters chose one Senatorial candidate, overwhelming numbers of Whites in the state chose the other.

Sixteen years after the Voting Rights Act and Blacks' first unfettered opportunity to vote, Black voting is becoming more pluralistic and divided. In many ways a natural development, this division has come about at a time when White voting appears more unified both in the Democratic primaries and the general election. If the trend continues, the power of the Black's ballot, which King envisioned as the strongest weapon of change, will be reduced to supporting seniority and incumbency, the old tools of the status quo, as the best, if inadequate, means for change in Southern politics.

The trend of declining Black voter turnout is nothing new, as Leslie Dunbar, formerly director of the Field Foundation, noted the Southwide, historic development earlier this year. "In each presidential election from 1964-1976, the proportion of Blacks casting their ballots was lower in the South than in the North and West... What we have," Dunbar said, "is a nation that in these years takes voting less and less seriously, with Black Southerners being the least interested of all .... I see no reason to expect voter interest, including that of Black Southerners, to rise unless the issues at contest become stronger and differences between parties and candidates more real."

For Southern politicians, the Miller-Talmadge contest shows clearly some of the results of trends Dunbar observes. With almost every viable White politicians' record spoiled by at least a moment or two of racism (if not usually considerably more), the yardstick for more and more Black leaders will be the "here and now" politics of who can offer real help. The past will be for them little indication of the real political differences. And until those differences between candidates are so contrasting and real to the Black electorate that there is really only one choice again, the present is the future for more and more Black voters regardless of the candidate's past. [source: Southern Changes Magazine, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1980, pp. 6-8, 22-23; Betty Norwood Chaney is senior editor of Southern Changes magazine. ]

No comments:

Post a Comment