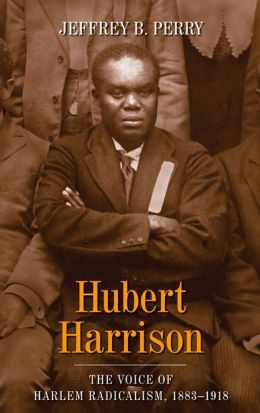

From a book review in Z-Magazine's November 2008 issue, by Bill Fletcher, "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" -- Jeffrey Perry has constructed a masterful examination of the life of the little known, though immensely significant, Black radical Hubert Harrison. In the first volume of what Perry promises to be a two volume work, Perry examines Harrison from birth till 1918, ending just prior to Harrison’s entrance into the back-to-Africa movement of Marcus Garvey.

Harrison, a native of St. Croix, was among the early immigrants to the U.S. from the non-Spanish-speaking Caribbean. This migration, which in fact continues through today, proved to be a transformative process in re-shaping “Black America.” The infusion of new blood into Black America from the West Indies brought with it significant leaders, not the least being Marcus Garvey and Hubert Harrison. It also brought with it changes in the basic culture and patterns of Black American politics.

"Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918," by Jeffrey Perry

Perry provides important background on St. Croix and its history, helping the reader to better understand the circumstances that shaped Harrison and his thinking. Central to this was the significance of both race and class for Harrison, a fact that would play out in his political evolution from his initial and militant critique of Booker T. Washington to his stint as a Socialist Party activist to his advocacy of a left-wing, revolutionary nationalist (though internationalist in many respects) race consciousness—an advocacy conducted both inside and outside the Garvey movement.

Harrison’s evolution is itself quite interesting in what it says about the early 20th century U.S. left. Harrison assumed that the Socialist Party (SP), with its anti-capitalist approach, would be a natural home. Nothing could have been further from the truth, however. The SP, badly divided between left and right wings, all but ignored race as a central feature of U.S. society. Even some of its most outspoken and courageous leaders, such as Eugene V. Debs, failed to appreciate the role of race and racism in the de-formation of U.S. democracy, the oppression of people of color, and the division of the working class.

Ultimately, Harrison concluded that the “radish socialism” (a term coined in the 20th century suggesting red or socialist on the outside, and white or white racist on the inside) offered no future for radical politics or for the Black freedom struggle. Interestingly, this did not result in Harrison moving away from radicalism, but rather he began a process of redefining both Black politics and radical politics.

Harrison’s political “location” makes him a fascinating character. As Perry documents, it was Harrison who influenced the development of Marcus Garvey. Garvey chose to move away from Harrison’s anti-imperialism, and instead embraced a much less confrontational (and safer) politics, at least in the beginning. Harrison’s own personal weaknesses, including but not limited to managing funds, contributed to his being eclipsed by Garvey, who was much better at building organization. Again, as documented by Perry and contrary to popular mythology, Garvey was no more charismatic and no better a speaker than Harrison.

Hubert Harrison needs to be read and absorbed in order to appreciate the growth of 20th century Black radicalism. Mainstream history, including mainstream African American history, can blatantly overlook key players, organizations, and movements. Rather than getting a full appreciation of the development of a process, one gets only glimpses. This can be seen even in some examinations of Black radicalism when it is told through the biographies of “great” figures.

Perry examines Harrison as a man of and for a movement. This is not a book written by a Harrison sycophant, despite Perry’s deep admiration for Harrison. It is a critical examination of a pivotal figure at a key and poorly understood moment in time.

It is unfortunate that Perry chose to tell Harrison’s story in two volumes. Though there is much to say about Harrison and his life, the political challenges faced by Harrison and the choices he made need to be available in accessible form to activist readers.

That said, Hubert Harrison is an excellent work and a great contribution to scholarship in connection with Black radicalism. Perry must be applauded for introducing, and in some cases reintroducing, this influential, though paradoxically all-but-forgotten figure to scholars and activists of the 21st century. (source: Z-Magazine's November 2008)

No comments:

Post a Comment