"Comparing anything to Holocaust, slavery a mistake," by Kathleen Parker, Columbian Syndicated Columnist, on 28 November 2013 -- Meet Simile and Sui Generis.

Simile, to refresh memories, is a favorite rhetorical device of writers that compares two essentially unlike things that nonetheless have similar characteristics: The quarterback was like a locomotive.

Sui generis, the Latin phrase meaning unique or one of a kind, is a helpful restraint upon the former. Some things, even if they share certain characteristics, shouldn't be compared. Sui generis is the braking system on a rhetorical locomotive, or at least it should be. That was a metaphor, by the way, and not a very good one.

We in the news business could stand to apply the brakes to our runaway impulse to "similize." I personally love a good simile, which is often a way to inject levity into a column. But lately, we've seen instances of simile-itis that might have saved readers and viewers some angst, even if writers and pundits were left with less to say.

In recent weeks, we've heard news people and others compare Obamacare to Katrina and Iraq. Sarah Palin compared our national debt to slavery. Countless times in recent years we've seen "Nazi" applied to people with whose policies or politics we disagree, none so frequently as George W. Bush, though President Obama, too, has had a few turns.

All of the above are clearly sui generis and should be retired from any future similes unless they are referring to truly like things, not just a single person's impression of the world while musing on current events. Katrina is like Sandy because they were both natural disasters, though significantly more people died in Katrina than in Sandy. Iraq is sui generis and nothing like Vietnam, to which it was sometimes compared.

Nazis and the Holocaust shouldn't be compared to anything else. The systematic, state-sponsored extermination of 6 million Jews, as well as others, is sufficiently horrific to stand alone. Pro-lifers who sometimes characterize abortion as a Holocaust are probably not helping the cause of revelation.

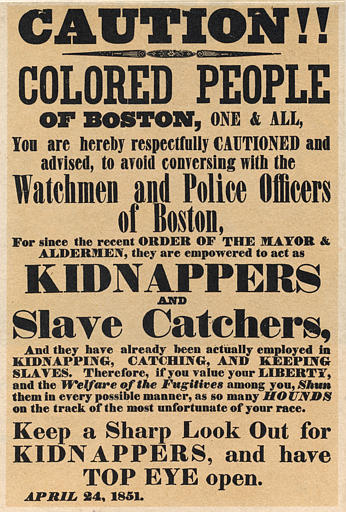

Finally, slavery merits its own place in America's memory. To compare it to anything else, especially something as mundane as debt, is wrong on its face. Indentured servitude to China might have been a better choice for Palin, who prefaced her remark with, "This isn't racist, but …" Note: Anytime you start a sentence with "This isn't racist, but …," you probably shouldn't finish it.

Rhetorical crime

These recent examples of similes gone awry raise two questions: What is the impulse that drives our need to make such comparisons? And why do we react so viscerally when we do?

The impulse is usually to elucidate, i.e., this is as bad as that. But it is also partly lazy. Do we really have so little imagination that all we can do is summon Katrina every time an administration fails to meet our expectations? Or Hitler to denote our impression of bad? Surely, it is a rhetorical crime to turn someone so evil into a cliché.

From a purely political perspective, the impulse may be driven by the desire to remind people of the past transgressions of political foes. Thus, when commentators say Obamacare is like Katrina, the mind flits from Barack Obama to George W. Bush and only the differences, rather than the single similarity of administrative incompetence, register: People died in Katrina and President Obama only wants to help people. Through subliminal jujitsu, the real comparison lands in the community psyche.

Conversely, as Salon political writer Brian Beutler suggested during a recent conversation, even Republicans may see benefits to this comparison in that it neutralizes the ongoing, negative liability of Katrina for the GOP. But then the cycle continues into absurdity. If Obamacare collapses and Republicans present Americans with Ryancare, we likely can expect Democrats to characterize every glitch as the GOP's Katrina II.

To the most important point, comparing a horrific tragedy or atrocity to anything else trivializes and diminishes it. By trying to capture, quantify and categorize others' suffering, we trespass on the sacred.

Some things are like nothing else — and should be left to rest in peace. [http://www.columbian.com/news/2013/nov/28/comparing-anything-to-holocaust-slavery-a-mistake/]