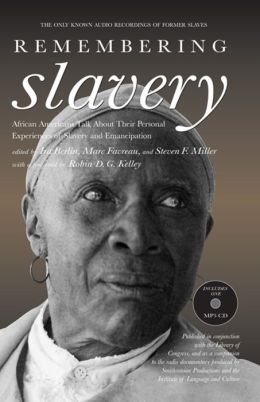

From the Library of Congress, "Slavery as Memory and History: Library Co-Publishes Cultural Archives," by Ira Berlin -- he Library of Congress, The New Press, Smithsonian Productions (the broadcasting and audio reproduction arm of the Smithsonian Institution) and the Institute of Language and Culture have joined together to make available the recollections of American ex-slaves as recorded more than a half-century ago. These are presented in a book with audiocassettes and a two-part radio documentary, both titled Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Freedom. Remembering Slavery is a unique enterprise that draws together -- in both printed word and recorded voices -- firsthand accounts of former slaves confronting owners, laboring in the field, maintaining families without the legitimating force of law and sustaining their dignity in the most degrading of circumstances. It seeks to put a human face on an inhumane social system that ended in the United States not that many generations ago, a system whose oldest survivors were the grandparents and great-grandparents of Americans still living. In so doing, Remembering Slavery allows readers and listeners to imagine the unimaginable, to reconsider the enslavement that so shaped the American past and whose legacy continues to cast a shadow over the American future.

The struggle over slavery's memory has been almost as intense as the struggle over slavery itself.

For many, the memory of slavery in the United States was too important to be left to the black men and women who experienced it directly. The stakes were too great. The American nation had invested much in slavery, maintaining it for more than two centuries and destroying it in a bloody Civil War that took nearly 1 million lives and destroyed billions of dollars in property. Indeed, slavery's demise elevated its importance and intensified the struggle over how it should be remembered by posterity.

Northerners who fought and won the war at great cost incorporated the abolitionists' perspective into their understanding of American nationality: slavery was evil, a great blot that had to be excised to realize the full promise of the Declaration of Independence. At first, even some white Southerners -- former slave-holders among them -- accepted this view, conceding that slavery had burdened the South as it had burdened the nation and declaring themselves glad to be rid of it.

But during the late 19th century, after attempts to reconstruct the nation on the basis of equality collapsed and demands for sectional reconciliation mounted, the portrayal of slavery changed. White Northerners and white Southerners began to depict slavery as a benign and even benevolent institution, echoing themes from the planters' defense of the antebellum order. They contrasted the violence and enmity of the postwar period with the supposed tranquillity of slave times, when happy slaves frolicked in the service of indulgent masters. Such views, popularized in the stories of Joel Chandler Harris and the songs of Stephen Foster, became pervasive during the first third of the 20th century.

REMEMBERING SLAVERY: AFRICAN-AMERICANS TALK ABOUT THEIR PERSONAL EXPERIENCES OF SLAVERY AND EMANCIPATION, By Ira Berlin

Still, the men and women who survived slavery had much to tell. And as the first generation of black people born in freedom came of age, fears that the slave experience would be lost forever troubled some scholars, particularly those at African American colleges for whom the new portrayal of slavery was an anathema. At Fisk University in Nashville, Southern University in Baton Rouge and Kentucky State University in Frankfort, historians initiated projects to interview former slaves. Their accounts, published privately or in the recently established Journal of Negro History during the 1920s, had little impact on the larger historical profession. White historians either discounted the validity of these accounts or saw them as peripheral to what they believed to be slavery's larger meaning in American life -- its role in the coming of the Civil War. According to historian Ulrich B. Phillips, whose view of slavery as a benign institution dominated the field, the "asseverations of politicians, pamphleteers and aged survivors" were hopelessly tainted, unfit to use even as a "supplement" to other, superior sources. By and large, the ex-slave narratives of the 1920s languished in the archives unread.

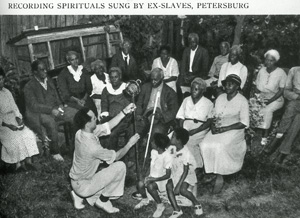

Recording Spirituals Sung by Ex-Slaves, Petersburg, Virginia

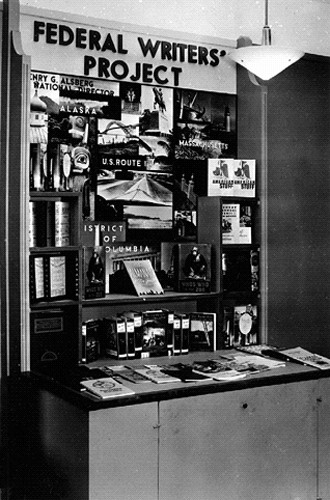

While ignored by historians, the narratives impressed folklorists, whose discipline gained new visibility in the 1930s. The Great Depression forced scholars, like all Americans, to reconsider the experience of the American people. In the study of history, as in many other disciplines, the emphasis was on the common folk, their language, song, art and stories. The New Deal's Federal Writers' Project -- one of several efforts to employ artists, musicians and actors -- gloried in the celebration of everyday Americans. Among its tasks was the collection of firsthand biographies of ordinary American people.

To this end, a special section of the Federal Writers' Project, directed first by John A. Lomax, then by Benjamin A. Botkin, and finally by Sterling A. Brown, took up the task that black scholars had begun in the 1920s. Lawrence Reddick of Kentucky State University, who in 1935 had expanded his earlier work into the Ohio Valley under the auspices of Federal Emergency Relief Administration, bridged the work of black scholars and the new, more expansive federal effort. Between 1936 and 1938, project-sponsored interviewers in 17 states collected the reminiscences of thousands of former slaves. In the process, they produced tens of thousands of pages of typescripts. In some cases, photographs of the interviewees and their families accompanied the documentation. Although the project was terminated before its completion, by the end of the decade some of the interviews were finding their way into print.

In 1939, control of the Federal Writers' Project passed from the federal government to the states, and in October of that year the interviews were deposited at the Library of Congress in Washington. There, Benjamin Botkin and his staff began evaluating and indexing the interviews, and two years later the "Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves" was placed in the Library's manuscript room.

Even before the Federal Writers' Project had expanded and extended Reddick's work in the Ohio Valley, another group of scholars had begun to record the words and songs of former slaves. Burdened by primitive recording equipment and the lack of precedents to guide them, these pioneering men and women -- who included John and Ruby Lomax and John's son Alan, Zora Neal Hurston, Roscoe Lewis and John Henry Faulk -- journeyed through the South trying to capture the voices of men and women who had experienced slavery. John Lomax, who had just been appointed honorary curator of the Library of Congress's Archive of Folk Song, led the effort; his and his son's work inspired Faulk, who was then beginning his graduate studies at the University of Texas. Others, working separately, followed the same course, often in consultation with Lomax and sometimes with the aid of Rosenwald fellowships. It would be Faulk, whose work extended into the early 1940s, who would eventually make the most important recordings of former slaves. His acetate discs would be deposited in the Library, where they were incorporated into the Archive of Folk Song, and in the University of Texas Library in Austin.

Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery Paperback; by Jerrold Hirsch

Historians of slavery continued to ignore this rich trove of evidence, although its existence became well known with the 1945 publication of Benjamin Botkin's Lay My Burden Down, the first of many anthologies drawn from the Federal Writers' Project narratives. Indeed, soon after the appearance of Botkin's volume, the Library of Congress microfilmed its collection to increase availability. Still, most historians treated the narratives with disdain. Some scholars condemned them as tainted by the unreliable memories of elderly informants, most of whom had been children at the time of slavery's demise; others questioned the statistical representativeness of the informants, who equaled roughly 2 percent of the ex-slave population in 1930 and, of course, only a tiny fraction of the slave population in 1860. Thus, through the 1960s, the slave narratives gathered dust in federal depositories, and many of those in state archives and private hands may have been destroyed or lost forever.

Beginning in the 1960s, though, stoked by the civil rights movement, a growing interest in slavery as the root cause of America's racial problem reawakened interest in the narratives. Concerned with slavery less as a cause of the Civil War than as the primary experience of millions of Americans, historians pored over the narratives as a means of gaining access to the slaves' voices. In 1972, when George P. Rawick compiled and published 19 volumes of the Library of Congress's transcripts under the title The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography, he saw as his "primary reason ... to make it possible to gain a perspective on the slave experience in North America from those who had been slaves." True to Rawick's promise, The American Slave immediately sparked a thorough rethinking of African American captivity and underlay major reinterpretations of slavery by John W. Blassingame, Eugene D. Genovese, Herbert G. Gutman, Lawrence Levine, Leon F. Litwack, Albert J. Raboteau, Thomas L. Webber and Rawick himself. Meanwhile, new collections of narratives were uncovered in state and local archives and brought to print. In 1977, when Rawick published a second series of 12 volumes drawn from state archives as well as the Library of Congress, the number of narratives in print reached 3,500. Another 10 volumes followed over the next two years, including the interviews compiled at Fisk University in the 1920s. Archivists and historians, searching out long-lost transcripts, published compilations reflecting the experience of slaves in particular states. From these volumes came yet others assembled for classroom use. The narratives, once dismissed as historical ephemera, had moved to the center of the study of slavery. By 1979, according to one historiographic review, the narratives were "as widely used as any other single source of data on American slavery."

The new scholars of slavery remained skeptical of the narratives' value, but for different reasons than their predecessors. Whereas Phillips had feared that the narratives would cast doubt on benevolent views of slavery, the revisionists worried that the narratives would foster just such a view of a kindly institution. They observed that the interviewers -- nearly all of whom were white Southerners -- had tended to select the most obsequious informants, "good Negroes" in the euphemism of the day. Noting that most of those interviewed were old and impoverished in a rigidly segregated society, slavery's new historians suspected that ex-slaves had told not what had actually happened but what their interviewers wanted to hear. After all, many of the interviewers were descended from the same people who had once owned the former slaves and their parents. Moreover, they were employed by a government agency, which led some interviewees to believe that the interviewers might help them obtain pensions, relief, or other benefits.

The interviewers themselves, of course, approached their work with their own beliefs and assumptions about slavery and its aftermath. Like most Americans, they generally accepted the notion that the Civil War had been a tragedy, Reconstruction a great mistake, and slavery as much an ordeal for white people as for black people. Even when the interviewers were sympathetic to the slaves' plight, they frequently patronized their subjects, calling them "uncle" and "aunt" and asking leading questions about sensitive issues of race relations, both historical and contemporary, that informants likely feared to answer straightforwardly. By their person and their approach, such interviewers evoked carefully hedged responses. Black men and women, drawing on a tradition that reached back into slavery, answered in a way that obliged the interviewer. Some interviewees preferred not to dredge up painful memories, much less share them with a white interviewer. Others answered in vague generalities that owed at least as much to their suspicions about the questioners as to the dimness of their recollections. A common pattern was to characterize their own treatment under slavery as benign, while describing that of neighboring slaves as brutal. Although such testimony reflected the fact that master-slave relations varied greatly from place to place, the transference in which former slaves attributed to their neighbors that which had actually happened to them revealed both the complexity of contemporary race relations and the manner in which former slaves believed it necessary to cloak their experiences.

As scholars closely inspected the narratives and the records of the Federal Writers' Project, other problems emerged. They discovered that in preparing what project editors called "ex-slave stories," many interviewers edited the informants' words, eliminating references they found indelicate, implausible, personally objectionable or ideologically offensive. Moreover, interviewers often altered the dialect as well as the words of their informant -- sometimes to make them conform to popular caricatures of "authentic" black speech, sometimes to make them conform to standard English. In any case, the narratives were rarely verbatim transcriptions. As a rule, they were reconstructions of conversations based on notes taken by the interviewer. Most of the narratives might best be considered fair summaries. A few were little more than fabrications, far more indicative of the historical memory and racial attitudes of white Southerners in the 1930s than of the lives of black slaves of the 1850s.

But, for all these and other problems, the corpus of narratives had great historic value. Many of the interviews -- particularly those taken by sympathetic interviewers -- evoked compelling remembrances of slavery of the sort it is impossible to fabricate. Former slaves were often eager to tell their tales, even to the most condescending of interviewers. Some had lost their fear of retaliation, prefacing their remarks with a warning that their interviewer might not like what they had to say, but they had to speak their minds. Although some interviewers may have dismissed their accounts -- a few went so far as to record their displeasure or dissent in footnotes to their transcripts or memos to their superiors -- many accepted them. The age of the former slaves, and the respect traditionally granted elderly people in Southern society, often provided an opportunity for slaves to speak openly and forcefully. Moreover, the administrators of the Federal Writers' Project, aware of how the former slaves' testimony was being adulterated, issued directives against such revisions, which restrained some of the more zealous editors and curbed the more outlandish dialect renderings.

Viewed from this perspective, the narratives were like every other historical source: they had strengths and weaknesses. If they were in some respects tainted, so too were other sources of slavery -- including title records produced by slaveholders and their white supporters. The historian's task was, as always, to employ them in ways that maximized their utility. The best scholars of slavery have used them critically and cautiously, carefully evaluating the quality of each narrative, verifying the ex-slave's memory against other sources and sometimes even sifting through multiple versions of the same interview. Thus, the narratives have become subject to all the requirements of any other historical source.

While the typescript narratives, readily available in print, became a standard source for the study of slavery, historians gave little attention to the sound recordings of the ex-slaves. During the 1960s, the Archive of Folk Song at the Library of Congress transferred its recordings from the fragile aluminum and acetate discs to 10-inch tape reels, but the sound remained scratchy and often inaudible; not until the mid-1980s did they attract a group of linguists interested in the evolution of African American English. Led by Guy Bailey, Natalie Maynor and Patricia Cukor-Avila, they began to transcribe the sound recordings and, in 1991, their book, The Emergence of Black English: Text and Commentary, presented detailed transcriptions of the tapes. Other scholars, most notably Jeutonne P. Brewer of the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, have since developed improved versions.

Linguists found in the recordings an extraordinarily rich opportunity to study the development of Black English Vernacular. Viewing the recordings as primary texts, they not only discovered new ways of understanding the transformation of language in the African American community but also developed new standards to measure how faithful Federal Writers' Project interviewers had been to their subjects' words. Moreover, during the 1990s, new techniques of digitizing or "remastering" the old aluminum and acetate discs have made a fuller rendition possible and, in some cases, made intelligible material that had previously been incomprehensible. In so doing, they raised new questions about the written typescripts and gave new importance to the voice recordings.

The recordings, like the typescripts, are as problematic as historical sources. Their small number made it impossible to view them as statistically representative. While the interviewers, some of them the nation's most experienced folklorists, demonstrated great sensitivity in questioning aged former slaves, they admitted having difficulty gaining access to informants, since white authorities often viewed them as outside agitators. Harassed and threatened, weighted down with bulky and unwieldy equipment, the recorders had limited range. Moreover, since they worked outside the guidelines of the Federal Writers' Project, they had no particular reason or mandate for focusing on slavery, and their informants often preferred to talk about other matters. Indeed, the recordings tell more about the life after emancipation than before it.

Nonetheless, the recorded interviews had great value. The immediacy of the voices of men and women who had experienced enslavement provided listeners a link to a world of slaves and slave owners -- a world often relegated to the distant past. Through the medium of the spoken word, the slaves' memory exploded out of the archives into the here and now.

As a result of the monumental struggle for racial equality, legal segregation has been outlawed and constitutional equality enshrined in law. But the work of creating an egalitarian multiracial society continues, as the American people labor to fulfill the ideals of the Founders and grapple with issues left unresolved. As that struggle has intensified in the last decade of the 20th century, the issue of slavery has once again rushed to the fore. The debate over the proposed official apology for slavery, the creation of a presidential commission to advance a "national conversation" on race, the furor over affirmative action programs, the popularity of the cinematic rendition of the Amistad revolt and the appearance of a cover story on slavery in the nation's best-selling newsmagazine all suggest how fully the creation of an egalitarian society rests on the nation coming to terms with its slave past.

There are no longer any Americans who have direct, personal memories of slavery, but the historical memory of slavery remains central to Americans' sense of themselves and the society in which they live. [source: http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/9811/slavery.html]

Ira Berlin: Generations in Captivity: Slavery in America from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

No comments:

Post a Comment