From the New York Times, "Lincoln and the Copperheads," by Jennifer L.Weber, on 28 January 2013 -- In January 1863, Abraham Lincoln made a remarkable confession. He was, he told a senator, more worried about “the fire in the rear” than he was about the Confederates to his front.

The moment was a particularly dark one for the Union cause. After a winning spring in 1862, federal armies had few successes. This dismal story was especially true for the high-profile Army of the Potomac. It had been whipped at the Second Battle of Bull Run in August, come to a draw at Antietam (though Abraham Lincoln claimed that as a win) and been slaughtered at Fredericksburg in December. The army, poorly generaled for the first half of the war, reached a new low in January 1863 with the Mud March, an ill-conceived attempt to strike Robert E. Lee at Fredericksburg, Va. Shortly after the federals set out, the rain began. Man and beast bogged down in mud, and Gen. Ambrose Burnside, he of the flamboyant whiskers, ordered his men back to camp. Morale tanked.

Confidence at home was little better. Daunted by the summer’s losses, many Northern civilians had been ready to give Southerners their independence. The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which Lincoln issued after Antietam, had been highly divisive among civilians and soldiers alike. While many Northerners, in and out of uniform, could agree about fighting to save the Union, fighting to free the slaves was not immediately as palatable. As failures and disappointments mounted, the public was increasingly receptive to the Peace Democrats, a conservative wing of the party that demanded a return to “the Union as it was and the Constitution as it is.”

Peevish and bordering on paranoid, the Peace Democrats thought nearly everything the Lincoln administration did to prosecute the war was unconstitutional. Some of the more extreme peace men thought the war itself was illegal, since the Constitution was silent about secession.

Peace Democrats typically came from one of three backgrounds: strict constructionists in understanding the Constitution, people of Southern birth or heritage who now lived in the lower Midwest and or immigrants who had suffered from nativists’ hostility and worried that freed slaves would come north and take their jobs. Whatever their origins, these dissidents framed their objections in constitutional terms.

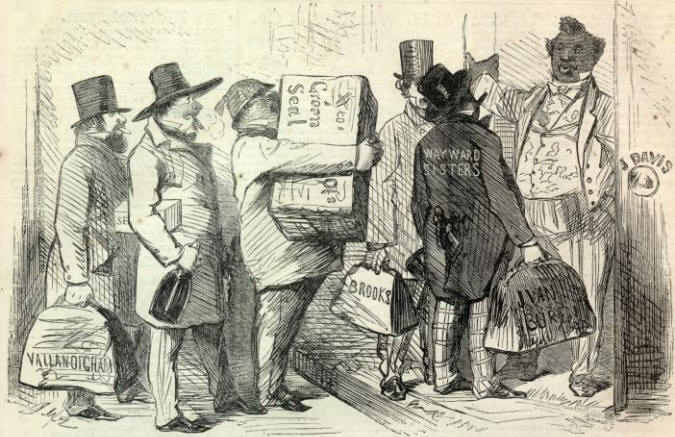

The conservatives, as they called themselves, had been in evidence since the beginning of the war. Some in Congress had denounced Lincoln from early on. But their visibility and activism grew as the war ground through its second year. In neighborhoods around the country, skittish Republicans reported that their dissident neighbors were calling Lincoln names, drilling in the woods and in some cases huzzahing for Jefferson Davis.

The peace men insisted that talk of the war being for the Union was untrue; the war, they said, was really about freeing slaves. When Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, conservatives both crowed about the accuracy of their interpretation of the war and raged that white men should die for the benefit of blacks.

The dissenters had no problem with slavery. They considered African-Americans something less than human, a subpar species fit for bondage. They also feared freedmen would come North and take jobs from white men. The racism that shot through their rhetoric was extreme, even by the standards of their own time.

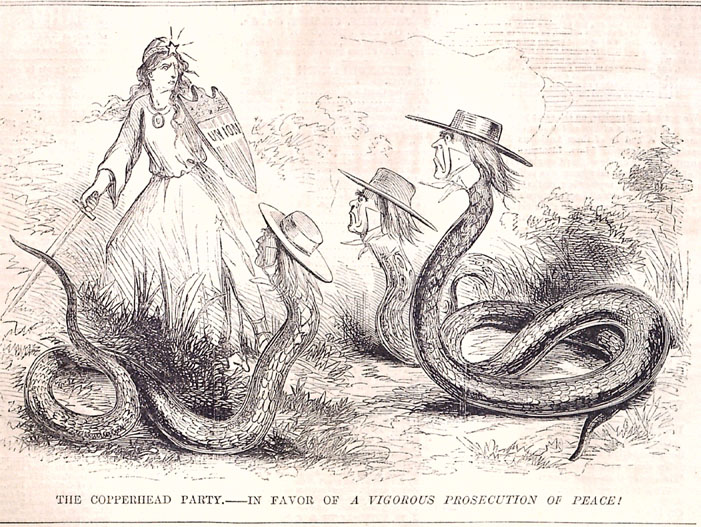

Disgusted Republicans termed them “Copperheads,” after the poisonous snake. Peace Democrats tried, with limited success, to turn that pejorative inside out. Another meaning for a “copperhead” at the time was the penny, which was made of copper. On one side of the penny was the head of Lady Liberty. Because they were deeply concerned about constitutional freedoms, Copperheads took to making pins of pennies, but with Lady Liberty being the featured side. They would wear these in their lapels to show where their political loyalties lay.

By January 1863, their assaults on Lincoln, combined with the poor performance of the armies, were taking a toll on civilian morale. Midwesterners spoke openly about seceding and establishing another new country or aligning with the Confederate States of America.

Lincoln’s critics were harsh, uncompromising and relentless. They said Lincoln was a tyrant, bent on amassing power and ruining democracy. They demanded an immediate end to hostilities, believing contrary to all available evidence that the Southern states would return to the Union if only Lincoln would stop the shooting. They wanted to keep slavery.

Their movement was never very organized, but it was influential. Peace Democrats were the naysaying chorus to Lincoln’s war aims reunion and emancipation. They took great umbrage at the ways Republicans chose to raise money and men to fight the war, including the nation’s first income tax, conscription and issuance of paper money. They were enraged that Lincoln, with Congress’s blessing, had suspended habeas corpus nationwide, essentially declaring martial law throughout the country.

In resisting the administration’s actions, peace men made army recruitment efforts far more complicated, encouraging soldiers to desert and draftees to flee, assaulting and sometimes killing enlistment agents and launching riots to resist the draft, which went into effect in March 1863.

Nevertheless, despite what Republicans repeatedly claimed, the vast majority were not traitors or Southern sympathizers. Some unquestionably were, and busted conspiracies and postwar admissions support the notion that some Copperheads committed treasonous acts. Most peace men, however, did not want to overthrow Lincoln except by the ballot. Even the idea of the war being illegal was a minority opinion within the movement. Most Copperheads did not want the Union to dissolve. They saw themselves as the loyal opposition, but they had huge blind spots. They never acknowledged the damage they did to the war effort, they lived in a state of obstinate refusal to face the very real threat the war posed and they never took full stock of Confederates, who insisted on independence, not reunion.

As Lincoln worried about the state of the home front, an important shift was taking place among soldiers. They were distressed about the 1862 elections, where Peace Democrats had performed quite well, gaining seats in the House, several state legislatures and the governorships of New York and New Jersey. The men thought Copperheads did not believe in their cause, honor their suffering or respect the sacrifice of their fallen friends.

The more they heard, the angrier Union soldiers became – to the point of threatening to cut off family and friends over political differences. A group of Indiana soldiers, for instance, accused their Copperhead friends of being cowards and traitors. “You are my enemy, and I wish you were in the rank of my open, avowed, and manly enemies, that I might put a ball through your black heart, and send your soul to the Arch Rebel himself,” they wrote. Such sentiments were shared through the war in thousands of letters from the front.

As a result, soldiers, even many Democrats, were increasingly aligning themselves with Lincoln. Along the way they became more open to emancipation, and by April 1863 most embraced Lincoln’s proclamation. The Copperheads, with their mystical thinking, never realized this, and they and the Democrats generally would pay a heavy political price for their misreading of the political landscape. (source: The New York Times)

No comments:

Post a Comment