From the UK Guardian "1493 by Charles C Mann – review: A lively account of how Columbus's voyage changed history," by Robin Blackburn, on 4 November 2011 -- The first attempts at world history too often had a bland textbook feel, or were bee-in-the-bonnet chronicles that reduced history to the impact of a single factor. Such approaches have been challenged by Niall Ferguson's snappy, opinionated, made-for-TV narratives, in which the rest of the world is taken to task for its tardiness in adopting such western "killer apps" as private property, free trade and scientific method.

1493: How the Ecological Collision of Europe and the Americas Gave Rise to the Modern World, by Charles Mann

Charles Mann's new book, with its ambitious title, is cheerfully eclectic rather than doctrinaire. It has a thankfully modest dose of western hubris. Like Ferguson, Mann starts with an accolade to the western corporation, laissez-faire and the wisdom of Adam Smith. But this is soon qualified as his narrative gets under way.

While over-pitching the "success" of colonial companies – and failing to note that "limited liability" was the key corporate innovation – Mann quickly concedes their role was a chequered one. He could have added that this was because on-the-spot company officials robbed their shareholders in a very modern way. He also pays detailed attention to a triumph of free trade on which Ferguson declines to dwell, the Atlantic slave trade – a "killer app" if ever there was one.

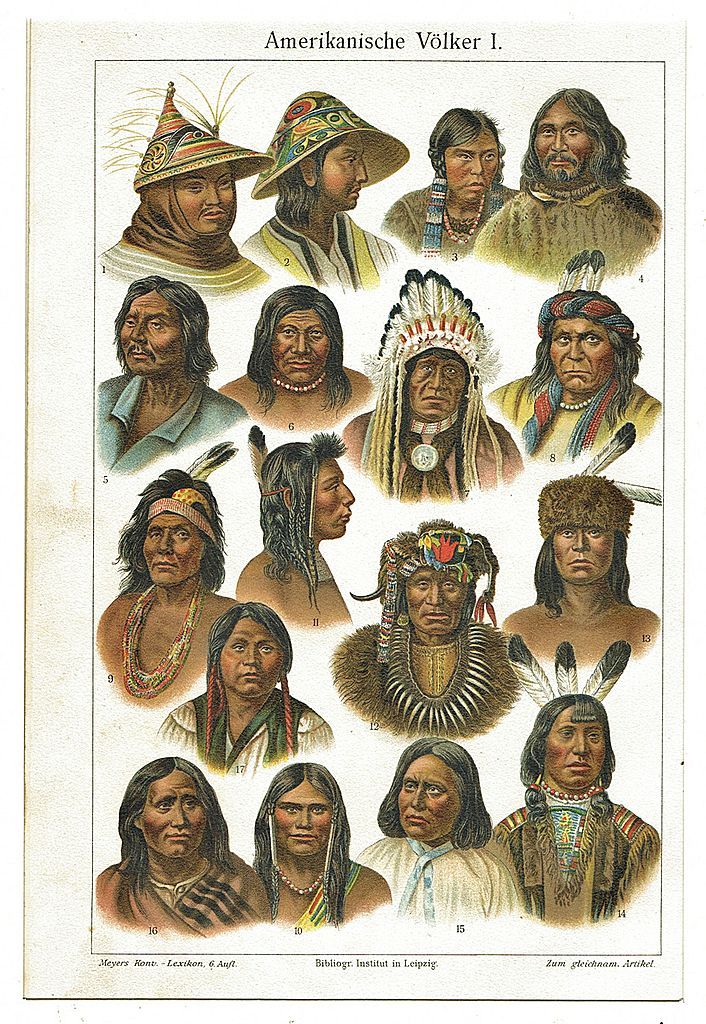

Mann avoids Ferguson's trademark triumphalism by giving an often critical account of his central topic – namely, the free and forced migration of peoples, plants, quadrupeds and parasites in the so-called "Columbian Exchange" inaugurated by the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Chapters of this story have been told before by Fernand Braudel, Pierre Vilar, William McNeill and others, but Mann can report new findings.

He does not supply a very detailed account of the "great dying" of the native peoples, but instead dwells on less well-known antecedents and consequences of Columbus's voyage in 1493. He makes a strong case for the role of the sweet potato and of the common-or-garden potato in helping Europe and China to mitigate, if not avoid, the "Malthusian trap" of overpopulation and famine. The book's extensive discussions of Chinese agriculture and manufacture are a strong feature even where they don't quite convince. Mann's account of the willful blunders of China's rulers down the ages helps to explain recurrent disasters.

If there is a rival candidate for the event that changed the course of history then it would have to be industrialisation, with its extraordinary impact on urbanisation, life expectancy, productivity and resource depletion. Mann sees the slave plantation as a forerunner of industrialism and notes the role of plantation products such as sugar, tobacco and coffee in stimulating mass consumer demand. In fact, he sees the discovery of the Americas as the prelude to the rise of industry but his case would have been strengthened by giving space to US cotton, a raw material easily adapted to industrial methods.

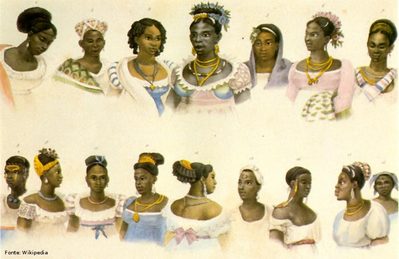

Mann is possessed of an intense curiosity rather than being driven by pattern-seeking. He gives a good account of Africans' resistance to slavery without asking why it stopped plantation growth in some cases (São Tomé and Hispaniola) and not in others (English Jamaica and French St Domingue). The contrast probably reflects a stronger commercial impulse. Likewise he pays welcome attention to the Haitian revolution (1791-1804) but stresses its effects on the planters of the Americas. Slaveholders in lands where there was a slave majority were "terrified" into accepting abolition. But in the 19th-century US South, Cuba and Brazil, territories where slaves were outnumbered by the free population, the planters exploited fear of bloody slave revolt to build new slave systems and rally non-slaveholders behind them.

Before reading this book I was unaware that south-east England was rife with malaria in the pre-industrial epoch. I am also pleased to have a keener appreciation of the vital roles of the earthworm and bumble bee. However, if you cover such a vast canvas the details can suffer. Mann argues that Africa was a continent of cattle herders and horse riders when this was not true of the huge forested zones of Central and West Africa, from where most of the slaves came. He suggests that slave plantations did not appear in West Africa because the soil and climate were unsuitable, yet surely the impediments were disease, poor security and unfavourable wind patterns? Quinine, fire power and steam power were to enable plantations after all by the early 20th century.

Mann is not averse to generalisation and counter-factual speculation but does not probe the larger questions concerning the history of capitalism – it was capitalism that furnished the demand for plantation produce by putting cash into the hands of wage workers.

Counter-factuals naturally appeal to those thinking about world history. Mann does not raise it, but what would have happened if the mighty fleet commanded by the 15th-century Chinese commander and explorer Zheng He had decided to sail eastwards, to a "new world", rather than westwards, to Africa? The Chinese imperial authorities, having debauched their paper currency, craved the stability and stimulus of silver. Chinese visitors to Mexico or Peru would have soon become aware of new-world silver and could have acquired it by selling Chinese porcelain and silk. China would also have been able to adopt the remarkable range of high-yield crops – maize, potatoes, etc – that the native peoples of the new world had domesticated. Instead of a Columbian exchange we might have had a Zheng He exchange and China might have developed a capitalism "with Chinese characteristics". Instead of the British forcing opium on China, perhaps a Chinese fleet would have invited the English to smoke tobacco and drink sweetened tea.

The value of 1493 stems from its lively and diligent accounts of the actual course of history – but its subtitle does incite one to speculate how different the course of "life on earth" might have been. (source: The UK Guardian; © 2013 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.)

No comments:

Post a Comment