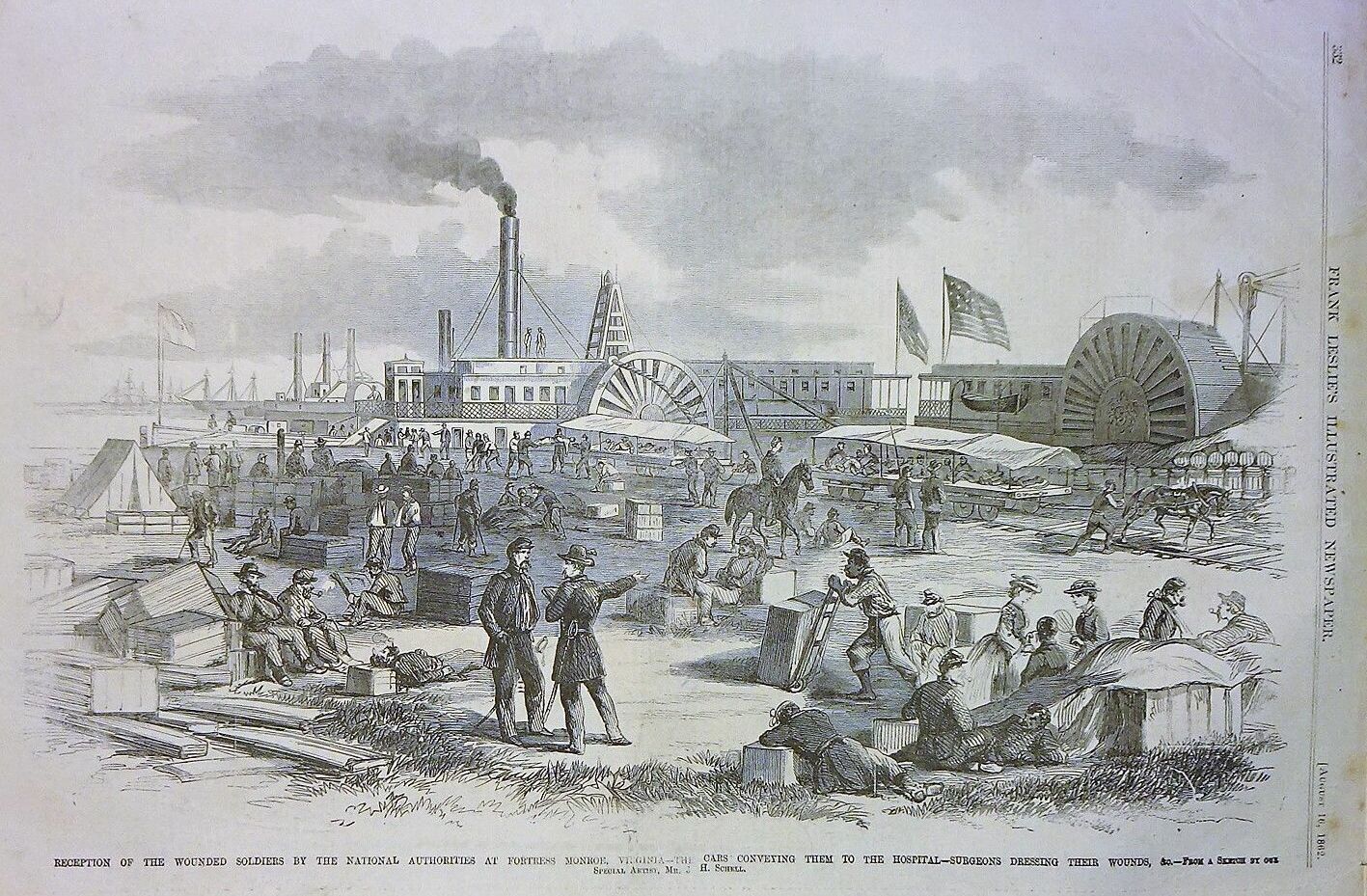

From The New York Times Disunion, "The Île à Vache: From Hope to Disaster," by Phillip W. Magness, on 12 April 2013 -- Virginia’s massive Fortress Monroe, operating under Union control from the beginning of the war, played witness to an unusual sight on the morning of April 14, 1863. For some six days prior the Ocean Ranger lay at anchor in sight of the fort’s guns as a steady stream of food and supplies were carried aboard. The brig’s main cargo, however, consisted of passengers — specifically 453 recently freed African-Americans — about to set sail for a new life in Haiti.

Fortress Monroe had been the site of the Civil War’s original emancipating act in 1861, when its commander, Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, issued the famous “contrabands order” refusing to return escaped slaves to their Confederate owners on the grounds that they were contrabands of war. In the intervening years, thousands of African-Americans made their way to the Union lines and availed themselves of this newfound pathway to freedom. Emancipation entailed an uncertain future though, and not all whites were willing or ready to accept the newly freed slaves as social or political equals.

The steady stream of “contrabands” to the fort also quickly turned into a flood in the wake of McClellan’s peninsula campaign, resulting in overcrowded and impoverished conditions in the camps that sprang up around the fort. In a December 1862 plea for charity, one Northern newspaper remarked of the destitute condition: “although the Government supplies them with food, they are in want of other necessaries that sustain life. Winter is hard by, and they must have blankets and comfortable clothing, or they will perish and die to our utter shame.” A correspondent to Frederick Douglass’s newspaper similarly deplored “their treatment by the officers of the government,” which “as a rule, has been brutal and cruel in the extreme.” The contrabands, he continued, had “long been promised, but never had [received] protection from the abuses of rebel sympathizers, and reasonable encouragement and opportunity to get a living.”

It was under these circumstances that the Ocean Ranger set sail, and while its associated policy of black colonization provided a source of controversy and distrust within the African-American community, the arrival of the ship was evidently seen by many freedmen as a means to escape poor conditions and an uncertain future in the United States. Throngs of contrabands reportedly amassed in the streets around the fort and on the wharf of nearby Hampton, Va., in hopes of securing passage. The vessel departed on the morning of April 14 to celebratory cheers, with one witness reporting that “seldom has a happier company left our shores.”

The genesis of the Ocean Ranger’s voyage was inextricably linked to the person of Bernard Kock, a cotton exporter who some months prior had secured a lease to the Île à Vache, a small, uninhabited island off the southern coast of Haiti. Bearing papers from the Haitian president, Fabre Geffrard, Kock approached the United States government with a scheme to colonize some 5,000 freed slaves on the island and employ them in agricultural production.

Though one of many similar proposals of varying character and design presented to Abraham Lincoln in the fall of 1862, Kock’s project benefited from its backing by the Haitian government and a stroke of good timing as the president searched for a pilot venture for his colonization program. Indeed, Lincoln most likely intended for the government’s agreement with Kock to coincide with his issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, fulfilling his longstanding habit of pairing emancipation and colonization together. The project was actually conceived at the White House on New Year’s Eve, 1862, amid late-night negotiations among Lincoln, Kock, Senator James Doolittle of Wisconsin and the longtime Washington powerbroker-turned-colonizationist standard-bearer Francis P. Blair Sr. With Blair boasting that the project marked “the beginning of the 2nd great Exodus” for African-Americans, Lincoln evidently affixed his signature to the Haitian colonization contract the following morning only hours before signing the more famous Emancipation Proclamation.

The terms of the contract pledged the United States government to pay $50 in transport per colonist, prompting Kock to assemble a group of New York investors to charter the first ship in early January. Yet the signed contract unexpectedly fell victim to a political rumor, alleging that Kock had struck a secret deal with Captain Raphael Semmes of the famed Confederate raider Alabama to transfer his human “cargo” into Southern hands while at sea. The charges were unfounded, yet sufficient to temporarily derail the project and perhaps an omen of other unexposed faults in Kock’s motives and ability.

While few records attest to the exact reasons for its revival, the suspended contract seems to have attracted presidential attention once again in early March 1863. According to Charles K. Tuckerman, one of the New York-based investors in the project, Lincoln summoned him to Washington and requested that he take on “the matter as a personal favor” to supplant Kock and his rumored personal baggage.

Captain Raphael Semmes

Despite the delay, the president desired that the project “should go on” and shortly thereafter gave his assent to a reconstituted contract with Tuckerman and Paul M. Forbes of the investor’s group. The pair had reportedly already spent a sizable sum on preparations for Kock’s project, suggesting a desire to recoup this investment from government funds played prominently into Tuckerman’s decision. The new contract terms restricted the project to a trial run of only 500 colonists, likely dampening the prospect of long term profitability from the venture. Forbes and Tuckerman jumped on the president’s offer though and quickly readied the Ocean Ranger for departure in just over a week’s time.

Belying the hope and promise exhibited by the contrabands-turned-colonists who departed Fortress Monroe on April 14, the mood of the voyage quickly soured. Though stricken from the contract, Kock had been retained by Forbes and Tuckerman to lead the voyage on account of his possession of the colony’s title from the Haitian government. He began to show autocratic tendencies almost immediately. Kock announced himself as “governor” of the colony, presented the passengers with contracts binding them to labor upon arrival, and either forced or swindled them into exchanging their money and valuables for a bizarre paper currency of his own design. To complicate matters, the ship suffered an outbreak of smallpox only three days out of port. By the day of their arrival at the Île à Vache on May 3, the disease had spread to another 20 passengers.

Though accounts of what happened next vary widely, Kock’s brief reign over the colony exhibited simultaneous signs of incompetence and a proclivity toward despotism. He seems to have viewed the colonists as his personal indentured workers on a sea cotton farming enterprise. The island itself was underprepared — by Kock’s own admission only two small dwellings had been constructed — and chronically undersupplied. A second ship carrying additional lumber and food cargo never sailed. Those afflicted by smallpox were quarantined to a “hospital” zone without supplies and tantamount to their effective abandonment on the beach. In a later defense of his actions, Kock looked upon the African-Americans in his company as a paternalistic charge in need of firm direction; for the Haitians, he had only contempt, deeming them “a lazy people, and inclined to avoid work whenever it is possible to do so.”

Bernard Kock

As the situation unraveled on the island, new tensions emerged between Kock, the New York investors, and their government sponsors. Kock blamed Forbes and Tuckerman for their failure to send a second supply ship. The investors, for their part, had lost faith in Kock’s leadership amid reports that he was misappropriating resources for the construction of his personal living quarters at the expense of the colonists. All the while, divisions emerged between both parties and Interior Secretary John P. Usher, under whose direction all colonization matters fell. Usher showed reluctance to release funds for either the Ocean Ranger’s voyage or a subsequent supply ship, and of equal significance, seems to have personally soured upon the entire colonization enterprise after about June of 1863. Even as the Ocean Ranger sailed, Usher had signaled an aversion to sending more colonists, and later charges of administrative negligence on his part may well have grounding in the revelation that the secretary had a personal financial stake in a competing colonization scheme in Panama.

Usher may have also found affirmation for keeping his distance as reports trickled in from Haiti. A lengthy letter on June 25 by James DeLong, United States Consul in the nearby Haitian port of Aux Cayes, provided forwarded secondhand reports from the island. Though DeLong’s testimony must be read with the potentially biasing knowledge that his son was invested in a competing colonization enterprise, it painted a thoroughly damning picture of Vache’s self-proclaimed “Governor.”

“Everything connected with the affairs on the Island is kept in the dark as much as possible,” wrote DeLong, and “no person is permitted to land on the Island without a passport except parties immediately connected with Mr. Kock in business.” He relayed an account from a witness who saw the colonists in absolute destitution, sleeping on open beaches and ramshackle huts. DeLong also enclosed a specimen of Kock’s self-printed currency — the only tender he offered in wages to the emigrants, which he then took as payment for food and goods “at an enormous profit” to himself in a veritable company shop arrangement.

Within two months of landing, Kock fled the island under threat of open revolt against his brutal labor system, though he also attempted to reinstate his version of “order” with local Haitian officials recruited from the mainland, with varying degrees of success. By early July, reports of the disastrous conditions prompted Forbes and Tuckerman to legally relieve Kock from the enterprise and place it under the direction of A.A. Ripka, a company agent sent ostensibly to place the colony on a sounder agricultural footing.

Ripka’s initial reports concealed still-deteriorating conditions, though Forbes and Tuckerman used them to press the Interior Department again for the release of funding. Paradoxically, the very same objections that Usher likely cited as grounds for denying the request were exacerbated by further inaction for want of capital. By the early fall the investors effectively pulled out, all attempts to plant a crop having failed. While the island reportedly possessed a favorable growing climate, it was “virgin and entangled soil” that required laborious clearing by hand. “Even corn and potatoes failed” in this environment and the surviving colonists began to desert, either to the Haitian mainland or to beach encampments elsewhere on Vache.

While Lincoln made no written response to the colony’s failure, the news eventually reached the White House and, according to one visitor in the late summer of 1863, left the president profoundly upset. “He told me … that the Negroes in the Cow Island settlement on the coast of Hayti were suffering intensely from a pest of ‘jiggers’ from which there seemed to be no escape or protection. His distress was as keen as it was sincere.”

The colony fell into virtual abandonment by early October, although numerous conflicting accounts from the island left Washington uncertain about the fate of the settlers. Likely prodded by the president after months of inattention, Usher appointed his old law partner D.C. Donnohue as special agent to investigate the site for the government. Finding the settlers still clothed in the same ragged surplus Union army uniforms that had been given to them at their departure from Fortress Monroe, Donnohue proceeded to oversee a relief expedition to carry survivors back to the United States. All said, of the initial 453 named colonists some 292 remained on Vache and an additional 73 had fled to the Haitian mainland. The remainder succumbed to disease and starvation.

Blame and finger-pointing for the Île à Vache disaster was well under way when the relief ship Marcia Day steamed up the Potomac and delivered the survivors to Alexandria, Va., on March 20, 1864. Kock alleged betrayal by both the government and the investors for failing to adequately supply his vessel. Forbes and Tuckerman pressed a claim against the government for reimbursement, noting that they received nothing of the contracted amount from Usher and faulting this lack of support for the experiment’s failure. Usher in turn used the disaster to deny the very same claim, and privately urged members of Congress to rescind federal funding for colonization entirely. The New York Times editor Henry Jarvis Raymond — himself one of the financiers backing Forbes and Tuckerman — blamed Usher’s failure to properly oversee the project from the beginning, noting, “How much he has had to do with causing its failure, how carefully he has so managed matters as to secure the defeat of the scheme, which he professed to be aiding, he does not state.”

Lincoln seems to have quietly let the matter drop after the settlers’ return, though his private secretary, John Hay, recorded the president’s dismay at the “thievery of … Kock” in his diary in July of 1864 after Congress, still reeling from the entire Vache incident, rescinded the remaining colonization budget. As for the colonists, the discriminatory challenges of a post-slavery United States awaited upon their return — as did a military recruiter, curiously seen waiting at the dockside as the Marcia Day arrived, ready to enlist its passengers to the Union war cause. (source: The New York Times)

No comments:

Post a Comment